Archive and Access: The Delhi State Archives

In this, the fifth entry in a series on the CIS-RAW Archive and Access project, Aparna Balachandran reports on two state archives located in Delhi, the National Archives of India, and the Delhi Archives.

Less visible than the National Archives of India is Delhi’s other state archive, the Delhi Archives. Unlike the NAI, which is located in Janpath at the heart of Lutyen’s Delhi, the Delhi Archives share a dilapidated building with the Delhi Institute of Heritage Research and Management, in a corner of the Qutub Institutional Area. The Delhi Archives were set up in 1972 to house documents and other material pertaining to the city of Delhi from as early as 1785, consisting mainly of the records of the Delhi Resident, and post 1857, the Commissioners’ Office. The collection is certainly not vast, but includes gems like the Mutiny Papers, the 600 page document on the trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar, papers on the post-rebellion demolition of Chandi Chowk and records on the setting up of Imperial Delhi.

Like the NAI, the Delhi archives are presently suffering from a lack of both funds and staff; the library, for instance, is in a state of complete disrepair. But we were assured by Sanjay Garg, who is in charge of the research room, that the archive itself is in good functioning order. The process of cataloguing its scattered Persian and Urdu records is underway, as are efforts to digitise the entire collection, about which I shall presently say more. From the very beginning, one of the important mandates for the setting up of the Delhi Archives was the acquisition of material “of interest” to Delhi (although the grounds for adjudgement seem fairly unclear) from other archival collections. We were told that records are regularly acquired from the Haryana and Punjab State Archives, and from the NAI; in addition, when funds allow, a historian is dispatched to the British Library to decide on what should be acquired from there. The Acquisitions Department also sends out a call in the papers at intervals for information about personal and family collections; sadly, we could not glean more information about this process because the person in charge was away on vacation.

In 2006, the Delhi archives launched an ambitious and much heralded project to digitise its entire collection; the process was still underway in early 2009. Documents, maps and photographs are being scanned and the visitor can access these on the two or three computers that are available for the purpose. Unfortunately, the computers are equipped with a search engine that is both difficult and cumbersome to use as well as being excruciatingly slow. This technology was developed by and borrowed from the NAI, where the online index is so ridden with misleading spellings as to make it practically unusable. Our brief use of the search engine at the Delhi Archives did not seem to throw up any glaring mistakes here at least – or perhaps we were dazzled by the visual materials now available online. Maps, the earliest going back to 1803; photographs including those of nationalist leaders; landscapes, cityscapes and monuments shot by colonial photographers; and hilariously, photos of the archive staff posing in the library stacks and offices are now all there to view with a mere click of the mouse. For a hundred rupees apiece moreover, the user can go home with the images of her choice on a pen-drive or a CD.

It is notable that the users that the Delhi State Archives and the NAI get are extremely different, a fact that impacts the way the two places function, particularly in terms of access. We were told at the research room at the NAI that the variety of users it gets has increased both in numbers and in diversity, so much so that a few years ago, archive officials decided that the category of “bonafide” user had to be expanded to include the non-academic user. Previously, access to the NAI was largely restricted to scholars armed with documentation proving their credentials; now, any citizen with some form of state identification is allowed access. While the bulk of users are still most certainly academics, the archive, or the idea of the archive, looms large in the public imagination. There are for instance, many novelists and film-makers who use the NAI. Not all are happy with their experience; some leave disappointed because the dry colonial records do not reveal, or immediately reveal the stories and detail they seek. The launching of state schemes - like the extension of martyrs pensions - that require written evidence from the archive also triggers off an increase in users. As more people and events are defined as part of, and co-opted into the National Movement, claimants to familial connections soar. We were told for example, that there was an influx of enquirers from certain villages in Haryana after a few families were able to substantiate their claims of being descendents of INA soldiers. Last year, the government agreed to grant the status of freedom fighters to the victims of the Jalliawala Bagh massacre in 1919 resulting in the arrival of those claiming to be descendents seeking evidence for the same (a complicated situation because of the vast discrepancies between the reported numbers of those killed in the British and Indian lists).

Interestingly, one case had a direct impact on the archival policy on access to documents. In the 1990s, with the increase in the number of heritage hotels in areas that included the former Princely States, claimants to land soared, with the NAI and the Home Ministry being dragged to court in several cases. As a result, the Accession Papers of the Princely States were made unviewable (a mystery was thereby solved when I repeated this information to a historian friend, frustrated that she was not allowed access to Dewas records from the '50s for some unknown reason). Interestingly, the largest category of new users consist of descendents of indentured labourers who left India in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to places like Mauritius, Jamaica, British Guiana, Trinidad and Fiji who want to trace their family histories. This is no easy task – these migrants appear in the lists that the colonial state kept of passages, medical examinations, births, deaths and marriages but were referred to by their first names only.

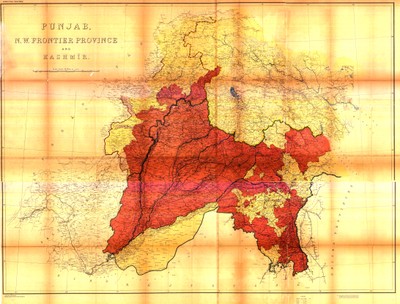

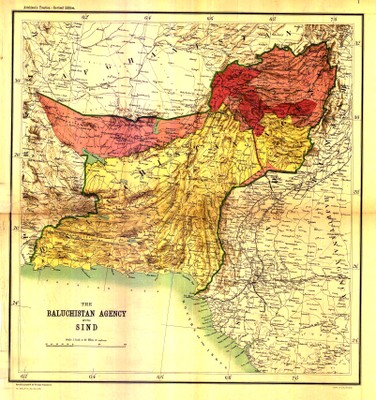

The profile of users at the Delhi Archives is quite different; most are non-academic and the number of scholars there could be as small as one or two a month. The non-academic user is also of a particular kind. Employees from various Delhi government departments are occasionally dispatched to the archive to refer to old files. But more importantly, the Delhi Archives are home to Delhi’s muncipal land records. A fifty to a hundred people a day arrive to look at, and make photo-copies of land records in order to settle disputes, make claims etc. The process is simple and routine and perhaps it is the fact of its being an everyday legal office that makes the Delhi Archives far simpler to access than a scholarly archive like the NAI. Entry to the NAI for instance, involves an arduous process of registration and verification; there is no such scrutiny at the Delhi Archives. Materials like border maps that are deemed as posing a threat to national security cannot be accessed at the NAI. Browsing through the maps at the Delhi Archives, we came across several border maps, a few of which we bought copies of that we can now presumably reproduce, disseminate or enlarge to hang on a wall.

We asked Sanjay Garg whether there was a policy at the Delhi to disallow the viewing of any of its records. Yes, he said, if the material was a threat to the nation’s safety. Had such a restriction ever been imposed? No, he answered.