Fishing is the New Black: Contemporary Art Imitates the Digital

Marshall Mcluhan once said, “Art at its most significant is a Distant Early Warning System that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it.” Philosophers, on the other hand, think about things in retrospect and hence, as much as Derrida’s writings about the collapse of the semiotic structures of capture and meaning say about the Digital age, Mark Rothko’s art, a generation ahead of Derrida in depicting this collapse, can say about the future that it saw in visceral and energetic forms. To understand Rothko’s paintings we must sit through a short history of the different epochs of Being and their epistemological shifts before we get to the Digital Age about which Rothko had violent and destructive premonitions.

According to Heidegger, the metaphysical age is one that lasts from Plato, where we began to explore the fundamental nature of being through ultimate, transcendental forms that show us diaphanous glimpses of themselves through earthly, imperfect forms to Nietzsche or Heidegger himself.[1]

Hans Belting, in his book Likeness and Presence talks about the transcendental signifiers during the Medieval Age as being transferred to the West by the Byzantines. These signifiers existed as iconotypes such as the Last Supper, the Resurrection, the Cross and the decapitation of John the Baptist which are not just treated as “art” by European cultures that inherited them but as objects of veneration that held in them the Holy itself.

|

A whole system of beliefs, superstitions, hopes and fears and, indeed, Being, is constructed by the people’s responses to this cathedral of a semiotic structure. While God creates primordial forms, the artist in this age is a cosmocrator who imitates God and creates ideal forms of these iconotypes that anchor meaning for everybody.[2] Ranging from Da Vinci’s perfect depiction of the Last Supper, the boundaries of the Byzantine dome of meaning is depicted through Michelangelo’s interior of the dome of the Sistine Chapel. While the curtains close on the Middle Ages, they drape with them, the iconotypes of Christianity. |

|---|

With the coming of the perspectable age of art, as Gebser puts it, three dimensional space is discovered through science and Copernicus where the world is shifted into a heliocentric system, the iconotypes permanently lose their centrality and as Derrida puts it, are substituted. While the sculptors like Brunelleschi were creating three dimensional art and the interiors of the Protestant Churches were vacant of iconotypes, artists like Bernini, by clinging on so deeply to the iconotypes that were dead, infused melancholy into their swansong.[3]

|

According to Heidegger, the aesthetic that follows is called “World Picture” which in art is similar to Oswald Spengler’s idea of infinite space. The transcendental signifier is that of infinity and the works of Dutch painters like Hobbema depict this metaphysical center of the age through their endless skies. Then the impressionists like Manet and Van Gogh break this three dimensional space further. During the modern age, Gebser’s integral sphere of consciousness is created through the paintings of Cezanne and Picasso who painted their archetypes on what he saw as its curved walls.[4] The archetypes, in a Jungian sense, are part of the universal subconscious and hence pervasive through all cultures unlike the Christian iconotypes of the Middle Ages. |

|

|---|

Mark Rothko, however, in his 1946 multi-forms, was busy orchestrating the Skywalkerian collapse of this integral sphere and taking the Jungian archetypes-myths, Gods, heroes- with him. Peter Barry argues in “Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural (1995)” that in the twentieth century, through a complicated sequence of historical and political, technological and scientific events, “these centers were destroyed or eroded”. The Great War destroys the notion of steady material progress and the Holocaust destroys the notion of Europe as the epi-center of human civilization. As a second coming of Copernican destruction of being, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity destroys the idea of time and space as fixed and central absolutes.

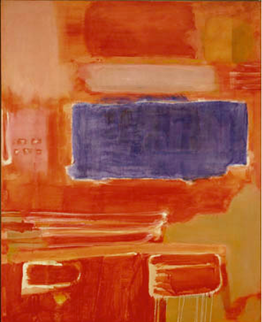

Rothko stopped naming his paintings because they unnecessarily curtailed the horizon of meaning so we will call it the sequence of the next three paintings, which depict the melting down of the modernist archetypes into blurred, overlapping chunks of colour.[5]

|

|  |

|---|

Gradually, these amorphous blobs of color congeal into squares and rectangles of intense light. These gradually intensifying shapes of light depict the semiotic vacancy and the absence of transcendental signifiers.

|

|---|

Rothko’s self-luminous squares and rectangles, however, perform an added function from dramatically enacting the past destruction which is to show premonitions of a future that will be dominated by the luminous screens of televisions, cell phones and digital constructions of meaning.[6]

|

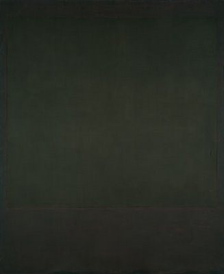

In the famous Seagrams Murals like the Black on Maroon, the paintings are no longer emanating light, standing as Cassandra like, diaphanous premonitions of a distant future but consist of colored rectangles engulfed by a menacing black band that gravitate the viewer into this world of semiotic vacancy, into what will become the digital world. |

|---|

By the time he is commissioned to do artwork for a Chapel in Houston that is dedicated to him (Rothko Chapel), all the transcendental signifiers that anchor any sort of meaning have been deconstructed and his canvases depict a triumph of the nothingness. When Hans Belting, in "The End of the History of Art?" ponders as to why "artists today often decline to participate in an ongoing history of art at all", it is precisely because of this rupture that Rothko and Derrida after him observed.

|

|---|

They almost set the stage for contemporary art, which is a private art of the particular artist who constructs her own meta-narrative by taking destroyed forms, dead batteries from the debris of previously ruptured spheres and attempts to stitch them together into a temporal Frankenstein’s monster of an art form.

|

|---|

Art now imitates the digital space as it isn’t an activity of vision and the artist isn’t a cosmocrator. In the Digital Humanities, knowledge isn’t practiced as in old academia which is a legatee of the Romantic conception of the genius as standing on the vanguard of society. Art in the contemporary age is simply anything that is taken out of its context of banality and knowledge in the digital age is simply any data set with commentary. Big data is the unacknowledged legislator of our time and not poets, as Heidegger would lament. John David Ebert likens the contemporary artist like Anselm Kiefer or Gerhard Richter to a fisherman of forms who has to hybridize old forms and discarded signifiers and re-territorialize them into new semiospheres. Nishant Shah, in a lecture on the ‘Histories of the Internet’, said that the best characterization of the Digital he knew was that of its etymology. The Latin Digitus signifies fingers, toes and perhaps the individual phalanges that, useless on their own, come together to make up the whole appendage like the functioning of Bit Torrent which takes apart a file into hundreds of pieces which it downloads individually from seeders around the world and stitches them back together. Indeed, it seems as if the ontology of the digital itself is imitated in the ontology of contemporary art which stitches together individually discarded and functionless, archaic forms. These radical vagaries of art forms caused by the collapse of the transcendental signifiers and the semiotic vacancy, seems to also be mirrored in the multi-forms that the Digital Humanities take in the mind of the Digital Humanists who have vastly differing conceptions of what the Digital Humanities really are/is. Just as art in the contemporary age is not anchored in a metaphysical center of meaning, Digital Humanists also lack an ontological fixity about their discipline which leads to the larger issue with digital humanities as a domain itself, wherein there is a concern about the rather diffused nature of the space, an invisible or missing locus; a critical or political standpoint.

[1]. Art after Metaphysics, John David Ebert, 2013

[2].Ibid.

[3].Ibid.

[4].Ibid.

[5].Ibid.

[6].Ibid.