Digital Gender: Theory, Methodology and Practice

Dr. Nishant Shah was a panelist at a workshop jointly organized by HUMlab and UCGS (Umeå Centre for Gender Studies) at Umeå University from March 12 to 14, 2014. He blogged about the conference.

Read the original published by HUMLAB Blog on March 20, 2014 here. Details of the workshop on Digital Gender can be seen here.

“When I was first invited to be a part of the Digital Gender conference curated by Anna Foka at the HUMlab in Umea, Sweden, there were many things that I had expected to find there: Historical approaches to understanding the relationship between digital technologies and practices and construction of gender, multi-modal and multi-disciplinary frameworks that examine the intersections of gender and the digital; Material and discursive descriptions of how we understand gender in contemporary realms. And indeed, I found it all there, and more, as a great collection of people, came together in dialogues of scholarly rigour, critical inquiry and political solidarity and empathy, to learn, to teach, to exchange research and scholarship. Given my past experiences of being at HUMlab and the incredible range of scholarship that was curated there, this came as no surprise.

|

|---|

| Above: Dr. Nishant Shah in HUMlab |

However, the one thing that stood out for me was an incredible session on Game Making conducted by Carl-Eric Engqvist. When I first saw it in the programme, I was apprehensive. What can Game Making have to do with digital gender? What would we learn from trying to design a game? I have been in ‘doing workshops’ before where things don’t always go as planned. Especially with the new ‘maker culture’ movements and DIY hipster phases, I have often found myself disappointed with workshops that focus too much on the technological and the interface. And I was in two minds about this – surely, we could have spent the time in more traditional academic experiences – round tables, discussion groups, or even just increased time for the participants to present their work. And so when the workshop began, I was waiting for it to make sense – to see what the game making’ workshop could have in store for the motley group of people that had assembled there.

Engqvist started off by showing us three games that have inspired him the most and what he wanted us to take as our points of thought and from that moment on, I knew we were in safe hands. Engqvist was not interested in games for gaming. He was interested in games as artefacts, as ways of thinking, as modes of engagement into exploring, reifying and concretizing many of the questions around power and empathy. And more than anything else, he presented with us the idea that games can be pedagogic, they can be learning tools; and though they might be designed for young players, they can be ways by which we translate our academic knowledge and research into practice.

What emerged in the subsequent two hours, was a great exercise in feminist methods and knowledge meeting new pedagogy and discussions. The group divided into two teams and set out to make a game that would be suitable for 8-10 year olds, and questions ideas of power and imbalance in their lives. Here are some things that I learned from the conversations:

- The nature of true power: One of the most interesting discussions that emerged was where the power resides. Scripted games often give us the illusion of power by making the power of the script writer invisible. While games are often open to creative interpretation and negotiation, these are only within the context of the constraints of the game. How do we design games that are then transparent about their own limitations? Can we think of a game that is about building the game rather than playing a game? Can we think of game outside of structures of competition and winning, closer to the designs of the Theatre of the Oppressed?

- Collective Empathy: The most dramatic revelation in the game making exercise was the engineering of empathy. There were many different suggestions on how to build empathy. One of the ideas was to put the players in simulations of real-life crises, asking them to take up different roles as antagonists and protagonists within the conflict, along with by-standers who can choose to be allies. However, drawing from legal narratives of rape, that demand that the rape victim be not subjected to re-living the experience through testimonies in court, we decided that it might be not fruitful to make participants re-live real-life trauma in the course of the game. Eventually, we decided that the way to escape this would be to let the participants be in control of their own simulations, and offer them ways of establishing trust and empathy.

- The power of narratives: In designing the narrative of the game, what came out was our own personal narratives of why we believe in the things that we do. How do we devise a game that has narratives of the everyday that can eventually transcend into becoming special? How does the playing of the game itself lead to repeated narratives, each customised to the situation? How do we create conditions and infrastructure that encourages users to iterate, repeat, remix and remediate ideas so that they become rich and layered narratives? And most importantly, how do we take something that is traumatic or troublesome, something that scares or angers us, and get the help of our fellow players, to reappropriate it, diffuse its hostile edge, and make it more amenable and something that we can cope with?

- DIY experiences: We recognised as a group, that we were more interested in a game that was about crafting experiences rather than designing learning goals. Or in other words, we wanted something so simple that it triggers something at the most visceral level, allowing the players to dig deeper into their own selves and come up with ideas that could resonate with the others. The ambition also was to have the gamers be in control of the intensity and thus define the parameters of their own gaming experience rather than be put into conditions or situations that might lead to further trauma.

- Teaching versus Learning: The largest chunk of our discussions pivoted around these two concepts. When designing a pedagogic game, how do we locate ourselves and the players? Do we assume the role of pedagogues who have specific messages to deliver, or do we assume the role of co-learners who will build a set of rules that create new conditions of playing every time? How do we further ensure that the games will have a feminist pedagogy of recursive and self-reflexive criticality along with a clear message of empathy, collaboration and togetherness?

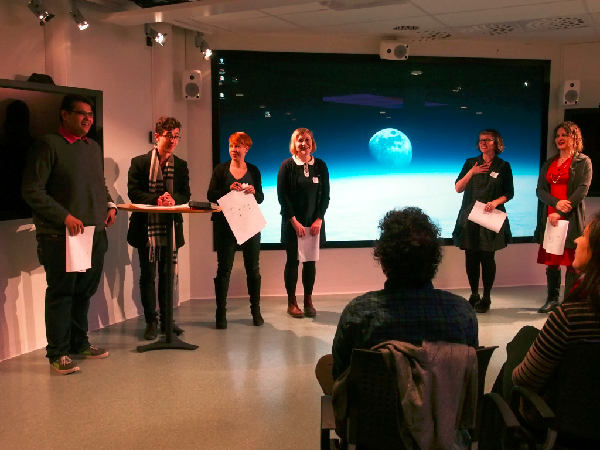

|

|---|

| Presentation of the game ‘Drawing It Out’ |

What emerged through these five learning principles was a simple game that we called ‘Drawing It Out’. Here are the rules of the game, followed by some pictures that emerged as we played the game ourselves in the group.

Game: Drawing It Out.

Players: 3-6.

Age: 8 and above

Materials: A number dice, a dice with different emotion words written on it: Shame, Anger, Frustration, Love, Fear, Hope. A tea-timer of 3 minutes. Sheets of blank paper, different coloured pens and pencils.

Instructions:

- Each member in the group rolls the number dice. The person with the highest roll gets to roll the emotion dice.

- The emotion dice lands on any one of the emotions. For example: Fear.

- The tea-timer is turned, and each player, sitting in a circle, gets three minutes to draw the one thing that they are afraid of.

- When the time is over, each player gets to talk about the thing that they are afraid of.

- Once everybody has explained their fear, they pass their sheet of paper to the person on the right. The tea-timer is turned. The next person draws something else on the sheet of paper – adding, remixing, morphing, changing the original drawing – to show how they can help in overcoming the particular fear. In the case of hopeful words like Love and Hope, the players add how they would increase and share in the feeling.

- Each time the tea-timer runs out, the paper moves on to the next person in the circle. The process is repeated till the sheet of paper reaches the person who had first drawn on it.

- At the end, each person looks at the sheet of paper they had begun with and the others talk about the ways in which they have added to the original drawing.

- The participants roll the number dice again and repeat the process. Participants are not allowed to draw the same thing if the emotion is repeated. The game can be played till there is interest or time to play it.

- The players get to take the sheets of remixed papers home with them as artefacts and signs of the trust established within the game.”

Dr. Nishant Shah is the co-founder and Director-Research at the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore, India. He is also an International Tandem Partner at the Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University, Germany and a Knowledge Partner with the Hivos Knowledge Programme, The Netherlands. Recently Dr. Nishant Shah visited HUMlab to participate in the conference “Digital gender: Theory, Methodology and Practice” (http://www.humlab.umu.se/digitalgender).