Blog

Technology-facilitated Gender-based Violence and Women’s Political Participation in India: A Position Paper

Read the full paper here.

Political participation of women is fundamental to democratic processes and promotes building of more equitable and just futures. Rapid adoption of technology has created avenues for women to access the virtual public sphere, where they may have traditionally struggled to access the physical public spaces, due to patriarchal norms and violence in the physical sphere. While technology has provided tools for political participation, information seeking, and mobilization, it has also created unsafe online spaces for women, thus often limiting their ability to actively engage online.

This essay examines the emotional and technological underpinnings of gender-based violence faced by women in politics. It further explores how gender-based violence is weaponised to diminish the political participation and influence of women in the public eye. Through real-life examples of gendered disinformation and sexist hate speech targeting women in politics in India, we identify affective patterns in the strategies deployed to adversely impact public opinion and democratic processes. We highlight the emotional triggers that play a role in exacerbating online gendered harms, particularly for women in public life. We also examine the critical role of technology and online platforms in this ecosystem – both in perpetuating and amplifying this violence as well as attempting to combat it.

We argue that it is critical to investigate and understand the affective structures in place, and the operation of patriarchal hegemony that continues to create unsafe access to public spheres, both online and offline, for women. We also advocate for understanding technology design and identifying tools that can actually aid in combating TFGBV. Further, we point to the continued need for greater accountability from platforms, to mainstream gender related harms and combat it through diversified approaches.

Privacy Policy Framework for Indian Mental Health Apps

The report’s findings indicate a significant gap in the structure and content of privacy policies in Indian mental health apps. This highlights the need to develop a framework that can guide organisations in developing their privacy policies. Therefore, this report proposes a holistic framework to guide the development of privacy policies for mental health apps in India. It focuses on three key segments that are an essential part of the privacy policy of any mental health app. First, it must include factors considered essential by the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 (DPDPA) such as consent mechanisms, rights of the data principal, provision to withdraw consent etc. Second, the privacy policy must state how the data provided by them to these apps will be used. Finally, developers must include key elements, such as provisions for third-party integrations and data retention policies.”

Click to download the full research paper here

Digital Rights and ISP Accountability in India: An Analysis of Policies and Practices

Read the full report here.

India's four largest Internet Service Providers (ISPs)—Reliance Jio, Bharti Airtel, Vodafone-Idea (Vi), and BSNL collectively serve 98% of India's internet subscribers, with Jio and Airtel commanding a dominant market share of 80.87%. The assessment comes at a critical juncture in India's digital landscape, marked by a 279.34% increase in internet subscribers from 2014 to 2024, alongside issues such as proliferation of internet shutdowns.

Adapting the Ranking Digital Rights' (RDR) 2022 methodology framework for its 2022 Telco Giants Scorecard, our analysis reveals significant disparities in governance structures and commitment to digital rights across these providers. Bharti Airtel emerges as the leader in governance framework implementation, maintaining dedicated human rights policies and board-level oversight. In contrast, Vi and Jio demonstrate mixed results with limited explicit human rights commitments, while BSNL exhibits the weakest governance structure with minimal human rights considerations. Notably, all ISPs lack comprehensive human rights impact assessments for their advertising and algorithmic systems.

The evaluation of freedom of expression commitments reveals systematic inadequacies across all providers. Terms and conditions are frequently fragmented and difficult to access, while providers maintain broad discretionary powers for account suspension or termination without clear appeal processes. There is limited transparency regarding content moderation practices and government takedown requests, coupled with insufficient disclosure about algorithmic decision-making systems that affect user experiences.

Privacy practices among these ISPs show minimal evolution since previous assessments, with persistent concerns about policy accessibility and comprehension. The investigation reveals limited transparency regarding algorithmic processing of personal data, widespread sharing of user data with third parties and government agencies, and inadequate user control over personal information. None of the evaluated ISPs maintain clear data breach notification policies, raising significant concerns about user data protection.

The concentrated market power of Jio and Airtel, combined with weak digital rights commitments across the sector, raises substantial concerns about the state of user privacy and freedom of expression in India's digital landscape. The lack of transparency in website blocking and censorship, inconsistent implementation of blocking orders, limited accountability in handling government requests, insufficient protection of user rights, and inadequate grievance redressal mechanisms emerge as critical areas requiring immediate attention.

As India continues its rapid digital transformation, our findings underscore the urgent need for both regulatory intervention and voluntary industry reforms. The development of standardised transparency reporting, strengthened user rights protections, and robust accountability mechanisms will be crucial in ensuring that India's digital growth aligns with fundamental rights and democratic values.

Do We Need a Separate Health Data Law in India?

Chapter 1.Background

Digitisation has become a cornerstone of India’s governance ecosystem since the National e-Governance Plan (NeGP) of 2006. This trend can also be seen in healthcare, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, with initiatives like the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM). However, the digitisation of healthcare has been largely conducted without legislative backing or judicial oversight. This has resulted in inadequate grievance redressal mechanisms, potential data breaches, and threats to patient privacy.

Unauthorised access to or disclosure of health data can result in stigmatisation, mental and physical harassment, and discrimination against patients. Moreover, because of the digital divide, overdependence on digital health tools to deliver health services can lead to the exclusion of the most marginalised and vulnerable sections of society, thereby undermining the equitable availability and accessibility of health services. Health data in the digitised form is also vulnerable to cyberattacks and breaches. This was evidenced in the recent ransomware attack on All India Institute of Medical Science, which, apart from violating the right to privacy of patients, also brought patient care to a grinding halt.

In this context, and with the rise in health data collection and uptick in the use of AI in healthcare, there is a need to look at whether India needs a standalone legislation to regulate the digital health sphere. It is also necessary to evaluate whether the existing policies and regulations are sufficient, and if amendments to these regulations would suffice.

This report discusses the current definitions of health data including international efforts, the report then proceeds to share some key themes that were discussed at three roundtables we conducted in May, August, and October 2024. Participants included experts from diverse stakeholder groups, including civil society organisations, lawyers, medical professionals, and academicians. In this report, we collate the various responses to two main aspects, which were the focus of the roundtables:

- In which areas are the current health data policies and laws lacking in India?

- Do we need a separate health data law for India? What are the challenges associated with this? What are other ways in which health data can be regulated?

Chapter 2. How is health data defined?

There are multiple definitions of health data globally. These include those incorporated into the text of data protection legislations or under separate health data laws. In the European Union (EU), the General Data Protection Regulation defines “data concerning health” as personal data that falls under special category data. This includes data that requires stringent and special protection due to its sensitive nature. Data concerning health is defined under Article(Article 4[15]) as “personal data related to the physical or mental health of a natural person, including the provision of healthcare services, which reveal information about his or her health status”. The United States has the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which was created to make sure that the personally identifiable information (PII) gathered by healthcare and insurance companies is protected against fraud and theft and cannot be disclosed without consent. As per the World Health Organisation (WHO), ‘digital health’ refers to “a broad umbrella term encompassing eHealth, as well as emerging areas, such as the use of advanced computing sciences in ‘big data’, genomics and artificial intelligence”.

2.1. Current legal framework for regulating the digital healthcare ecosystem in India

In India the digital health data had been defined under the draft Digital Information Security in Healthcare Act (DISHA), 2017, as an electronic record of health-related information about an individual. and includes the following: (i) information concerning the physical or mental health of the individual; (ii) information concerning any health service provided to the individual; (iii) information concerning the donation by the individual of any body part or any bodily substance; (iv) information derived from the testing or examination of a body part or bodily substance of the individual; (v) information that is collected in the course of providing health services to the individual; or (vi) information relating to the details of the clinical establishment accessed by the individual.

However, DISHA was subsumed into the 2019 version of the Personal Data Protection Act, called The Data and Privacy Protection Bill, which had a definition of health data and a demarcation between sensitive personal data and personal data. Both these definitions are absent from the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023. This makes uncertain what is defined as health data in India. It is also important to note that the health data management policies released during the pandemic relied on the definition of health data under the then draft of the Personal Data Protection Act.

(i) Drugs and Cosmetic Act, and Rules

At present, there is no specific law that regulates the digital health ecosystem in India. The ecosystem is currently regulated by a mix of laws regulating the offline/legacy healthcare system and policies notified by the government from time to time. The primary law governing the healthcare system in India is the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (DCA), 1940, read with the Drugs and Cosmetic Rules, 1945. These regulations govern the manufacture, sale, import, and distribution of drugs in India. The central and state governments are responsible for enforcing the DCA. In 2018, the central government published the Draft Rules to amend the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules in order to incorporate provisions relating to the sale of drugs by online pharmacies (Draft Rules). However, the final rules are yet to be notified. The Draft Rules prohibit online pharmacies from disclosing the prescriptions of patients to any third person. However, they also mandate the disclosure of such information to the central and state governments, as and when required for public health purposes.

(ii) Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, and Rules

The Clinical Establishments Rules, 2012, which are issued under the Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010, require clinical establishments to maintain electronic health records (EHRs) in accordance with the standards determined by the central government. The Electronic Health Record (EHR) Standards, 2016, were formulated to create a uniform standards-based system for EHRs in India. They provide guidelines for clinical establishments to maintain health data records as well as data and security measures. Additionally, they also lay down that ownership of the data is vested with the individual, and the healthcare provider holds such medical data in trust for the individual.

(iii) Health digitisation policies under the National Health Authority

In 2017, the central government formulated the National Health Policy (NHP). A core component of the NHP is deploying technology to deliver healthcare services. The NHP recommends creating a National Digital Health Authority (NDHA) to regulate, develop, and deploy digital health across the continuum of care. In 2019, the Niti Aayog, proposed the National Digital Health Blueprint (Blueprint). The Blueprint recommended the creation of the National Digital Health Mission. The Blueprint made this proposition stating that “the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has prioritised the utilisation of digital health to ensure effective service delivery and citizen empowerment so as to bring significant improvements in public health delivery”. It also stated that an institution such as the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM), which is undertaking significant reforms in health, should have legal backing.

(iv) Telemedicine Practice Guidelines

On 25 March 2020, the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines under the Indian Medical Council Act were notified. The Guidelines provide a framework for registered medical practitioners to follow for teleconsultations.

2.2. Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

There has been much hope for India’s data protection legislation in India to cover definitions of health data, keeping in mind the removal of DISHA and the uptick in health digitisation in both the public and private health sectors. The privacy/data protection law, the DPDPA was notified on 12 August 2023. However, the provisions have still not come into force. So, currently, health data and patient medical history are regulated by the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules (SPDI Rules), 2011. The SPDI Rules will be replaced by the DPDA as and when its different provisions are enforced. On 3 January 2025, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology released the Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025, for public consultation. The last date for submitting the comments is 18 February 2025.

Health data is regarded as sensitive personal data under the SPDI Rules. Earlier drafts of the data protection legislation had demarcated data as personal data and sensitive personal data, and health data was regarded as sensitive personal data. However, the DPDA has removed the distinction between personal data and sensitive personal data. Instead, all data is regarded as personal data. Therefore, the extra protection that was previously afforded to health data has been removed. The Draft Rules also do not mention health data or provide any additional safeguards when it comes to protecting health data. However, it exempts healthcare professionals from the obligations that have been put on data fiduciaries when it comes to processing children’s data. The processing has to be restricted to the extent necessary to protect the health of the child.

As seen so far, while there are multiple healthcare-related regulations that govern stakeholders – from medical device manufacturers to medical professionals – there is still a vacuum in terms of the definition of health data. The DPDPA does not clarify this definition. Further, there are no clear guidelines for how these regulations work with one another, especially in the case of newer technologies like AI, which have already started disrupting the Indian health ecosystem.

Chapter 3. Key takeaways from the health data roundtables

The three health data roundtables covered various important topics related to health data governance in India. The first roundtable highlighted the major concerns and examined the granular details of considering a separate law for digital healthcare. The second round table featured a detailed discussion on the need for a separate law, or whether the existing laws can be modified to address extant concerns. There was also a conversation on whether the absence of a classification absolves organisations from the responsibility to protect or secure health data. Participants stated that due to the sensitivity of health data, data fiduciaries processing health data could qualify it as significant data fiduciary under the the proposed DPDPA Rules (that were at the time of hosting the roundtables) yet to be published. The final roundtable concluded with an in-depth discussion on the need for a health data law. However, no consensus has emerged among the different stakeholders.

The roundtables highlighted that the different stakeholders – medical professionals, civil society workers, academics, lawyers, and people working in startups – were indeed thinking about how to regulate health data. But there was no single approach that all agreed on.

3.1. Health data concerns

Here, we summarise the key points that emerged during the three roundtables. These findings shed light on concerns regarding the collection, sharing, and regulation of health data.

(i) Removal of sensitive personal data classification

In the second roundtable, there was a discussion on the removal of the definition of health data from the final version of the DPDPA, which also removed the provision for sensitive personal data; health data previously came under this category. One participant stated that differentiating between sensitive personal data and data was important, as sensitive personal data such as health data warrants more security. They further stated that without such a clear distinction, data such as health status and sexual history could be easily accessed. Participants also pointed out that given the current infrastructure of digital data, the security of personal data is not up to the mark. Hence a clear classification of sensitive and personal data would ensure that data fiduciaries collecting and processing sensitive personal data would have greater responsibility and accountability.

(ii) Definition of informed consent

The term ‘informed consent’ came up several times during the roundtable discussions. But there was no clarity on what it means. A medical professional stated that in their practice, informed consent applies only to treatment. However, if the patient’s data is being used for research, it goes through the necessary internal review board and ethics board for clearance. One participant mentioned that the Section 2(i) of the Mental Healthcare Act (MHA), 2017 defines informed consent as

consent given for a specific intervention, without any force, undue influence, fraud, threat, mistake or misrepresentation, and obtained after disclosing to a person adequate information including risks and benefits of, and alternatives to, the specific intervention in a language and manner understood by the person; a nominee to make a decision and consent on behalf of another person.

Neither the DPDA nor the Draft DPDPA Rules define informed consent. However, the Draft DPDA Rules state that the notice given by the data fiduciary to the data principal must use simple, plain language to provide the data principal with a full and transparent account of the information necessary so that they can provide informed consent to process their personal data.

A stakeholder pointed out that consent is taken without much nuance or the option for choice or nuance. Indeed, consent is often presented in non-negotiable terms, creating power imbalances and undermining patient autonomy. Suggested solutions include instituting granular and revocable consent mechanisms. This point also emerged during the third roundtable, where it was highlighted that consenting to a medical procedure was different from consenting to data being used to train AI. When a consent form that a patient or caregiver is asked to sign gives the relevant information and no choice but to sign, it creates a severe power imbalance. Participants also emphasised that there was a need to assess if consent was being used as a tool to enable more data-sharing or a mechanism for citizens to be given other rights, such as the reasonable expectation that their medical information would not be used for commercial interests, especially to their own detriment, just because they signed a form. One suggested way to tackle this is for there to be greater demarcation of the aspects a person could consent to. This would give people more control over the various ways in which their data is used.

(iii) Data sharing with third parties

Discussions also focused on the concerns about sharing health data with third parties, especially if the data is transferred outside India. Data is/can be shared with tech companies and research organisations. So the discussions highlighted the regulations and norms governing how such data sharing occurs despite the fragmented regulations. For instance:

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Ethical guidelines for application of Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical Research and Healthcare mandate strict protocols for sharing health data, but these are not binding. They state that the sharing of health data by medical institutions with tech companies and collaborators, must go through the ICMR and Health Ministry’s Screening Committee. This committee has strict guidelines on how and how much data can be shared and how it needs to be shared. The process also requires that all PII is removed and only 10 percent of the total data is permitted to be shared with any collaborator outside of any Indian jurisdiction.

- Companies working internationally have to comply with global standards like the GDPR and HIPAA, highlighting the gaps in India’s domestic framework which leaves the companies uncertain of which regulations to comply with. There is a need to balance the interests of startups that require more data and better longitudinal health records, and the need for strong data protection, data minimisation, and storage limitation.

(iv) Inadequate healthcare infrastructure

With respect to the implementation challenges associated with health data laws, participants noted that, currently, the Indian healthcare infrastructure is not up to the mark. Moreover, smaller and rural hospitals are not yet on board with health digitisation and may not be able to comply with additional rules and responsibilities. In terms of capacity as well, smaller healthcare facilities lack the resources to implement and comply with complex regulations.

3.2. Regulatory challenges

Significant time was spent on discussing the regulatory challenges and deficiencies in India’s healthcare infrastructure. The discussion primarily revolved around the following points:

(i) State vs. central jurisdiction

Under the Constitutional Scheme, legislative responsibilities for various subjects are demarcated between the centre and the states, and are sometimes shared between them. The topics of public health and sanitation, hospitals, and dispensaries fall under the state list set out in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. This means that state governments have the primary responsibility of framing and implementing laws on these subjects. Under this, local governance institutions, namely local bodies, also play an important role in discharging public health responsibilities.

(ii) Do we bring back DISHA?

During the conversation about the need for the health data regulation, participants brought up that there had been an earlier push for a health data law in the form of DISHA, 2017. But this was later abandoned. DISHA aimed to set up digital health authorities at the national and state levels to implement privacy and security measures for digital health data and create a mechanism for the exchange of electronic health data. Another concern that arose with respect to having a central health data legislation was that, as health is a state subject, there could be confusion about having a separate, centralised regulatory body to oversee how the data is being handled. This might come with a lack of clarity on who would address what, or which ministry (in the state or central government) would handle the redressal mechanism.

3.3. Are the existing guidelines enough?

Participants highlighted that enacting a separate law to regulate digital health would be challenging, considering that the DPDPA took seven years to be enacted, the rules are yet to be drafted, and the Data Protection Board has not been established. Hence, any new legislation would take significant resources, including manpower and time.

In this context, there were discussions acknowledging that although the DPDPA does not currently regulate health data, there are other forms of regulation and policies that are prescribed for specific types of interventions when it comes to health data; for example, the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, 2020, and the Medical Council of India Rules. These are binding on medical practitioners, with penalties for non-conforming, such as the revoking of medical licenses. Similarly the ICMR guidelines on the use of data in biomedical research include specific transparency measures, and existing obligations on health data collectors that would work irrespective of the lack of distinction between sensitive personal data and personal data under the DPDPA.

However, another participant rightly pointed out that the ICMR guidelines and the policies from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare are not binding. Similarly, regulations like the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines and Indian Medical Council Act are only applicable to medical practitioners. There are now a number of companies that collect and process a lot of health data; they are not covered by these regulations. Although there are multiple regulations on healthcare and pharma, none of them cover or govern technology. The only relevant one is the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, which say that AI cannot advise any patient; it can only provide support.

Chapter 4. Recommendations

Several key points were raised and highlighted during the three roundtables. There were also a few suggestions for how to regulate the digital health sphere. These recommendations and points can be classified into short-term measures and long-term measures.

4.1. Short-term measures

We propose two short-term measures, as follows:

(i) Make amendments to the DPDPA Introduce sector-specific provisions for health data within the existing framework. The provisions should include guidelines for informed consent, data security, and grievance redressal.

(ii) Capacity-building Provide training for healthcare providers and data fiduciaries on data security and compliance.

4.2. Long-term measures

We offer six long-term measures, as follows:

(i) Standalone legislation Enact a dedicated health data law that

- Defines health data and its scope; ● Establishes a regulatory authority for oversight; and

- Includes provisions for data sharing, security, and patient rights.

(ii) National Digital Health Authority

Establish a central authority, similar to the EU’s Health Data Space, to regulate and monitor digital health initiatives.

(ii) Cross-sectoral coordination

Develop mechanisms to align central and state policies and ensure seamless implementation.

(v) Technological safeguards

Encourage the development of AI-specific policies and guidelines to address the ethics of using health data.

(vi) Stringent measures to address data breaches

Increase the trust of people by addressing data breaches, and fostering proactive dialogue between patients, medical community, government and civil society. Reduce the exemption for data processing, such as that granted to the state for healthcare

Conclusion

The roundtable discussions highlighted the fragmented nature of the digital health sphere, and the issues that emanate from such a fractured polity. Considering the variations in the healthcare infrastructure and budget allocation across different states, the feasibility of enacting a central digital health law requires more in-depth research. The existing laws governing the offline/legacy health space also need careful examination to understand whether amendments to these laws are sufficient to regulate the digital health space.

The Centre for Internet and Society’s comments and recommendations to the: Report on AI Governance Guidelines Development

With research assistance by Anuj Singh

I. Background

On 6 January 2025, a Subcommittee on ‘AI Governance and Guidelines Development’ under the Advisory Group put out the Report on AI Governance Guidelines Development, which advocated for a whole-of-government approach to AI governance. This sub-committee was constituted by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) on November 9, 2023, to analyse gaps and offer recommendations for developing a comprehensive framework for governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As various AI governance conversations take centre stage, this is a welcome step, and we hope that there are more opportunities through public comments and consultations to improve on this important AI document.

CIS’ comments are inline with the submission guidelines, we have provided both comments and suggestions based on the headings and text provided in the report.

II. Governance of AI

The subcommittee report has explained its reasons for staying away from a definition. However, it would be helpful to set the scope of AI, at the outset of the report, given that different AI systems have different roles and functionalities. Having a clearer framework in the beginning can help readers better understand the scope of the conversation in the report. This section also states that AI can now “perform complex tasks without active human control or supervision”, while there are instances where AI is being used without an active human control, there is a need to emphasise on the need for humans in the loop. This has also been highlighted in the OECD AI principles which this report draws inspiration from.

A. AI Governance Principles

A proposed list of AI Governance principles (with their explanations) is given below.

While referring to the OECD AI principles is a good first step in understanding the global best practices, it is suggested that an exercise in mapping of all global AI principles documents published by international and multinationals organisations and civil society is undertaken, to determine principles that are most important for India. The OECD AI principles also come from regions that have a better internet penetration, and higher literacy rate than India, hence for them the principle of “Digital by design governance” would be possible to be achieved but in India, a digital first approach, especially in governance, could lead to large scale exclusions.

B. Considerations to operationalise the principles

1. Examining AI systems using a lifecycle approach

The sub committee has taken a novel approach to define the AI life cycle. The terms “Development, Deployment and Diffusion” have not been seen in any of the major publications about AI lifecycle. While academicians (e.g. Chen et al. (2023), De Silva and Alahakoon (2022)) have pointed out that the AI life cycle contains the following stages - design, development and deployment, others (Ng et al. (2022) have defined it as “data creation, data acquisition, model development, model evaluation and model deployment. Even NASSCOM’s Responsible AI Playbook follows the “conception, designing, development and deployment, as some of the key stages in the AI life cycle. Similarly the OECD also recognised “i) ‘design, data and models’ ii) ‘verification and validation’; iii) ‘deployment’; and iv) ‘operation and monitoring’.” as the phases of the AI life cycle. The subcommittee hence could provide citation as well as a justification of using this novel approach to the AI lifecycle, and state the reason for moving away from the recognised stages. Steering away from an understood approach could cause some confusion amongst different stakeholders who may not be as well versed with AI terminologies and the AI lifecycle to begin with.

2. Taking an ecosystem-view of AI actors

While the report rightly states that multiple actors are involved across the AI lifecycle, it is also important to note that the same actor could also be involved in multiple stages of the AI lifecycle. For example if we take the case of an AI app used for disease diagnosis. The medical professional can be the data principal (using their own data), the data provider (using the app thereby providing the data), and the end user (someone who is using the app for diagnosis). Similarly if we look at the example of a government body, it can be the data provider, the developer (if it is made inhouse or outsourced through tenders), the deployer, as well as the end user. Hence for each AI application there might be multiple actors who play different roles and whose roles might not be static.

While looking at governance approaches, the approach must ideally not be limited to responsibilities and liabilities, especially when the “data principal” and individual end users are highlighted as actors; the approach should also include rights and means of redressal in order to be a rights based people centric approach to AI governance.

3. Leveraging technology for governance

While the use of techno-legal approach in governance is picking up speed there is a need to look at existing Central and State capacity to undertake this, and also look at what are the ways this could affect people who still do not have access to the internet. One example of a techno legal approach that has seen some success has been the Bhumi programme in Andhra Pradesh that used blockchain for land records, however this also led to the weakening of local institutions, and also led to exclusion of marginalised people Kshetri (2021). It was also stated that there was a need to strengthen existing institutions before using a technological measure.

Secondly, while the sub committee has emphasized on the improvements in quality of generative AI tools, there is a need to assess how these tools work for Indian use cases. It was reported last year that ChatGPT could not answer all the questions relating to the Indian civil services exam, and failed to correctly answer questions on geography, however it was able to crack tough exams in the USA. In addition to this, a month ago the Finance Ministry has advised government officials to refrain from using generative AI tools on official devices for fear of leakage of confidential information.

Thirdly, the subcommittee needs to assess India’s data preparedness for this scale of techno legal approach. In our study which was specific to healthcare and AI in India, where we surveyed medical professionals, hospitals and technology companies, a common understanding was that data quality in Indian datasets was an issue, and that there was somewhere reliance on data from the global north. This could be similar in other sectors as well, hence when this data is used to train the system it could lead to harms and biases.

III. GAP ANALYSIS

A. The need to enable effective compliance and enforcement of existing laws.

The sub-committee has highlighted the importance of ensuring that the growth of AI does not lead to unfair trade practices and market dominance. It is hence important to analyse whether the existing laws on antitrust and competition, and the regulatory capacity of Competition Commission of India are robust enough to deal with AI, and the change in technology and technology developers.

There is also an urgent need to assess the issues that might come under the ambit of competition throughout the lifecycle of AI, including in areas of chip manufacturing, compute, data, models and IP. While the players could keep changing in this evolving area of technology there is a need to strengthen the existing regulatory system, before looking at techno legal measures.

We suggest that before a techno legal approach is sought in all forms of governance, there is an urgent need to map the existing regulations both central and state and assess how they apply to regulating AI, and assess the capacity of existing regulatory bodies to regulate issues of AI. In the case of healthcare for example there are multiple laws, policies and guidelines, as well as regulatory bodies that apply to various stages of healthcare and various actors and at times these regulations do not refer to each other or cause duplications that could lead to lack of clarity.

Below we are adding our comments and suggestions certain subsections in this section on The need to enable effective compliance and enforcement of existing laws

1. Intellectual property rights

a. Training models on copyrighted data and liability in case of infringement

While Section. 14 of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957 provides copyright holders with exclusive rights to copy and store works, considering the fact that training AI models involves making non-expressive uses of work, a straightforward conclusion may not be drawn easily. Hence, the presumption that training models on copyrighted data constitutes infringement is premature and unfounded.

This report states “The Indian law permits a very closed list of activities in using copyrighted data without permission that do not constitute an infringement. Accordingly, it is clear that the scope of the exception under Section 52(1)(a)(i) of the Copyright Act, 1957 is extremely narrow. Commercial research is not exempted; not-for-profit 10 institutional research is not exempted. Not-for-profit research for personal or private use, not with the intention of gaining profit and which does not compete with the existing copyrighted work is exempted. “

Indian copyright law follows a ‘hybrid’ model of limitations and exceptions under s.52(1). S. 52(1)(a), which is the ‘fair dealing’ provision, is more open-ended than the rest of the clauses in the section. Specifically, the Indian fair dealing provision permits fair dealing with any work (not being a computer programme) for the purposes of private or personal use, including research.

If India is keen on indigenous AI development, specifically as it relates to foundation models, it should work towards developing frameworks for suitable exceptions ,as may be appropriate. Lawmakers could distinguish between the different types of copyrighted works and public-interest purposes while considering the issue of infringement and liability

b. Copyrightability of work generated by using foundation models

We suggest that a public consultation would certainly be a useful exercise in ensuring opinions and issues of all stakeholders including copyright holders, authors, and users are taken into account.

C. The need for a whole-of-government approach.

While the information existing in silos is a significant issue and roadblock, if the many guidelines and existing principles have taught us anything, it is that without specificity and direct applicability it is difficult for implementers to extrapolate principles into their development, deployment and governance mechanisms. The committee assumes a sectoral understanding from the government on various players in highly regulated sectors such as healthcare or financial services. However, as our recent study on AI in healthcare indicates, there are significant information gaps when it comes to shared understanding of what data is being used for AI development, where the AI models are being developed and what kind of partnerships are being entered into, for development and deployment of AI systems. While the report also highlights the concerns about the siloed regulatory framework, it is also important to consider how the sector specific challenges lend themselves to the cross-sectoral discussion. Consider that an AI credit scoring system in financial services is leading to exclusion errors.

Additionally, consider an AI system being deployed for disease diagnosis. While both use predictive AI, the nature of risk and harm are different. While there can be common and broad frameworks to potentially test efficacy of both AI models, the exact parameters for testing them would have to be unique. Therefore, it will be important to consider where bringing together cross-sectoral stakeholders will be useful and where it may need more deep work at the sector level.

IV. Recommendations

1. To implement a whole-of-government approach to AI Governance, MeitY and the Principal Scientific Adviser should establish an empowered mechanism to coordinate AI Governance.

We would like to reiterate the earlier section and highlight the importance of considering how the sector specific challenges lend themselves to the cross-sectoral discussion. While the whole of government approach is good as it will help building a common understanding between different government institutions, this approach might not be sufficient when it comes to AI governance. It is because this is based on the implicit assumption that internal coordination among various government bodies is enough to manage AI related risks.

2.To develop a systems-level understanding of India’s AI ecosystem, MeitY should establish, and administratively house, a Technical Secretariat to serve as a technical advisory body and coordination focal point for the Committee/ Group.

The Subcommittee report states at this stage, it is not recommended to establish a Committee/ Group or its Secretariat as statutory authorities, as making such a decision requires significant analysis of gaps, requirements, and possible unintended outcomes. While these are valid considerations, it is necessary that there are adequate checks and balances in place. If the secretariat is placed within MeitY then safeguards must be in place to ensure that officials have autonomy in decision making. The subcommittee suggests that MeitY can bring officials on deputation from other departments. Similarly the committee proposes bringing experts from the industry, while it is important for informed policy making, there is also risk of regulatory capture. Setting a cap on the percentage of industry representatives and full disclosure of affiliations of experts involved are some of the safeguards which can be considered. We also suggest that members of civil society are also considered for this Secretariat.

3.To build evidence on actual risks and to inform harm mitigation, the Technical Secretariat should establish, house, and operate an AI incident database as a repository of problems experienced in the real world that should guide responses to mitigate or avoid repeated bad outcomes.

The report suggests that the technical secretariat will develop an actual incidence of AI-related risks in India. In most instances, an AI incident database will assume that an AI related unfavorable incident has already taken place, which then implies that it's no longer a potential risk but an actual harm. This recommendation takes a post-facto approach to assessing AI systems, as opposed to conducting risk assessments prior to the actual deployment of an AI system. Further, it also lays emphasis on receiving reports from public sector organizations deploying AI systems. Given that public sector organizations, in many cases, would be the deployers of AI systems as opposed to the developers, they may have limited know-how on functionality of tools and therefore the risks and harms.

It is important to clarify and define what will be considered as an AI risk as this could also depend on stakeholders, for example losing clients due to an AI system for a company is a risk, and so is an individual being denied health insurance because of AI bias. With this understanding, while there is a need to keep an active assessment of risks and the emergence of new risks, the Technical Secretariat could also undergo a mapping of the existing risks which have been highlighted by academia and civil society and international organisations and begin the risk database with that. In addition, the “AI incident database” should also be open to research institutions and civil society organisations similar to The OECD AI Incidents Monitor.

4. To enhance transparency and governance across the AI ecosystem, the Technical Secretariat should engage the industry to drive voluntary commitments on transparency across the overall AI ecosystem and on baseline commitments for high capability/widely deployed systems.

It is commendable that the sub committee in this report extends the transparency requirement to the government, with the example of law enforcement. This would create more trust in the systems and also add the responsibility on the companies providing these services to be compliant with existing laws and regulations.

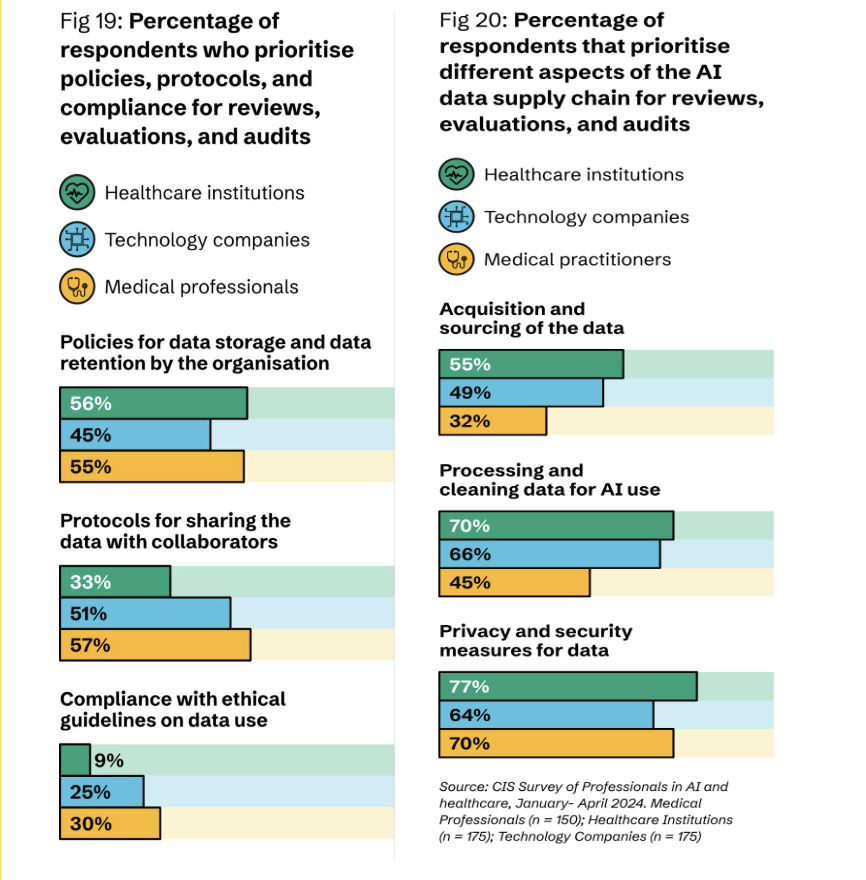

While the transparency measures listed will ensure better understanding of processes of AI developers and deployers, there is also a need to bring in responsibility along with transparency. While this report also mentions ‘peer review by third parties’, we would also like to suggest auditing as a mechanism to undertake transparency and responsibility. In our study on AI data supply chain & auditability and healthcare in India, (which surveyed 150 medical professionals, 175 respondents from healthcare institutions and 175 respondents from technology companies); revealed that 77 percent of healthcare institutions and 64 percent of the technology companies surveyed for this study, conducted audits or evaluations of the privacy and security measures for data.

5. Form a sub-group to work with MEITY to suggest specific measures that may be considered under the proposed legislation like Digital India Act (DIA) to strengthen and harmonise the legal framework, regulatory and technical capacity and the adjudicatory set-up for the digital industries to ensure effective grievance redressal and ease of doing business.

It would be necessary to provide some clarity on where the process to the Digital India Act is currently. While there were public consultations in 2023, we have not heard about the progress in the development of the Act. The most recent discussion on the Act was in January 2025, where S Krishnan, Secretary, Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY), stated that they were in no hurry to carry forward the draft Digital India Act and regulatory framework around AI. He also stated that the existing legal frameworks were currently sufficient to handle AI intermediaries.

We would also like to highlight that during the consultations on the DIA it was proposed to replace the Information Technology Act 2000. It is necessary that the subcommittee give clarity on this, since if the DIA is enacted, this reports section III on GAP analysis especially around the IT Act, and Cyber Security will need to be revisited.

The Centre for Internet and Society’s comments and feedback to the: Digital Personal Data Protection Rules 2025

Rule 3 - Notice given by data fiduciary to data principal - Under Section 5(2) of the DPDP Act, when the personal data of the data principal has been processed before the commencement of the Act, then the data fiduciary is required to give notice to the data principal as soon as reasonably practicable. However, the Rules fail to specify what is meant by reasonably practicable. The timeline for a notice in such circumstances is unclear.

- In addition, under Rule 3(a) the phrase “be presented and be understandable independently” is ambiguous. It is not clear whether the consent notice has to be presented independently of any other information or whether it only needs to be independently understandable and can be presented along with other information.

- In addition to this we suggest that the need for “privacy by design” mentioned in the earlier drafts is brought back, with the focus on preventing deceptive design practices (dark patterns) being used while collecting data.

Rule 4 - Registration and obligations of Consent Manager- The concept of independent consent managers, similar to account aggregators in the financial sector, and consent manager platforms in the EU is a positive step. However, the Act and the Rules need to flesh out the interplay between the Data Fiduciary and the Consent Managers in a more detailed manner, for example, how does the data fiduciary know if a data principal is using a consent manager, and under what circumstances can the data fiduciary bypass the consent manager, what is the penalty/consequence, etc.

Rule 6 - Reasonable security safeguards - While we appreciate the guidance provided in terms of the measures for security such as “encryption, obfuscation or masking or the use of virtual tokens”, it would also be good to refer to the SPDI Rules and include the example of the The international Standard IS/ISO/IEC 27001 on Information Technology - Security Techniques - Information Security Management System as an illustration to guide data fiduciaries.

Rule 7 - Intimation of personal data breach - As per the Rules, the data fiduciary on becoming aware of any personal data breach is required to notify the data principal and the Data Protection Board without delay; a plain reading of this Rule suggests that data fiduciary has to report the breach almost immediately, and this could be a practical challenge. Further, the absence of any threshold (materiality, gravity of the breach, etc) for notifying the data principal means that the data fiduciary will have to inform the data principal about even an isolated data breach which may not have an impact on the data principal. In this context, we recommend the Rule be amended to state that the data fiduciary should be required to inform the Data Protection Board about every data breach, however the data principal should be informed depending on the gravity and materiality of the breach and when it is likely to result in high risk to the data principal.

- Whilst the Rules have provisions for intimation of data breach, there is no specific provision requiring the Data Fiduciary to take all steps necessary to ensure that the Data Fiduciary has taken all necessary measures to mitigate the risk arising out of the said breach. Although there is an obligation to report any such measures to the Data Principal (Rule 7(1)(c)) as well as to the DPBI (Rule 7(2)(b)(iii)), there is no positive obligation imposed on the Data Fiduciary to take any such mitigation measures. The Rules and the Act merely presume that the Data Fiduciary would take mitigation measures, perhaps that is the reason why there are notification requirements for such breach, however the Rules and the Act do not put any positive obligation on the Data Fiduciary to actually implement such measures. This would lead to a situation where a Data Fiduciary may not take any measures to mitigate the risks arising out of the data breach, and be in compliance with its legal obligations by merely notifying the Data Principal as well as the DPBI that no measures have been taken to mitigate the risks arising from the data breach. In addition, the SPDI Rules state that in an event of a breach the body corporate is required to demonstrate that they had implemented reasonable security standards. This provision could be incorporated in this Rule to emphasize on the need to implement robust security standards which is one of the ways to curb data breaches from happening, and ensure that there is a protocol to mitigate the breach.

Rule 10 - Verifiable consent for processing of personal data of child or of person with disability who has a lawful guardian - The two mechanisms provided under the Rules to verify the age and identity of parents pre-suppose a high degree of digital literacy on the part of the parents. They may either give or refuse consent without thinking too much about the consequences arising out of giving or not giving consent. As there is always a risk of individuals not providing the correct information regarding their age or their relationship with the child, platforms may have to verify every user’s age; thereby preventing users from accessing the platform anonymously. Further, there is also a risk of data maximisation of personal data rather than data minimisation; i.e parents may be required to provide far more information than required to prove their identity. One recommendation/suggestion that we propose is to remove the processing of children's personal data from the ambit of this law, and instead create a separate standalone legislation dealing with children’s digital rights. Another important issue to highlight here is the importance of the Digital Protection Board and its capacity to levy fines and impose strictures on the platforms. We have seen from examples from other countries that platforms are forced to redesign and provide for better privacy and data protection mechanisms when the regulator steps in and imposes high penalties

Rule 12 - Additional obligations of Significant Data Fiduciary - The Rules do not clarify which entities will be considered as a Significant Data Fiduciary, leaving that to the government notifications. This creates uncertainty for data fiduciaries, especially smaller organisations that might not be able to set up the mechanisms and people for conducting data protection impact assessment, and auditing. The Rule provides that SDFs will have to conduct an annual Data Protection Impact Assessment. While this is a step in the right direction, the Rules are currently silent on the granularity of the DPIA. Similarly for “audit” the Rules do not clarify what type of audit is needed and what the parameters are. It is therefore imperative that the government notifies the level of details that the DPIA and the audit need to go into in order to ensure that the SDFs actually address issues where their data governance practices are lacking and not use the DPIA as a whitewashing tactic.There is also a need to reduce some of the ambiguity with regards to the parameters, and responsibilities in order to make it easier for startups and smaller players to comply with the regulations. In addition, while there is a need to protect data and increase responsibility on organisations collecting sensitive data or large volumes of data, there is a need to look beyond compliance and look at ways that preserve the rights of the data principal. Hence significant data fiduciaries should also be given the added responsibility of collecting explicit consent from the data principal, and also have easier access for correction of data, grievance redressal and withdrawal of consent.

Rule 14 - Processing of personal data outside India - As per section 16 of the Act the government could, by notification, restrict the transfer of data to specific countries as notified. This system of a negative list envisaged under the Act appears to have been diluted somewhat by the use of the phrase “any foreign State” under the Rules. This ambiguity should be addressed and the language in the Rules may be altered to bring it in line with the Act. Further, the rules also appear to be ultra vires to the Act. As per the DPDP Act, personal data could be shared to outside India, except to countries which were on the negative list, however, the dilution of the provision through the rules appears to have now created a white list of countries; i.e. permissible list of countries to which data can be transferred.

Rule 15 Exemption from Act for research, archiving or statistical purposes- While creating an exception for research and statistical purposes is an understandable objective, the current wording of the provision is vague and subject to mischief. The objective behind the provision is to ensure that research activities are not hindered due to the requirements of taking consent, etc. as required under the Act. However the way the provision is currently drafted, it could be argued that a research lab or a research centre established by a large company, for e.g. Google, Meta, etc. could also seek exemptions from the provisions of this Act for conducting “research”. The research conducted may not be shared with the public in general and may be used by the companies that funded/established the research centre. Therefore there should be further conditions attached to this provision, that would keep such research centers outside the purview of the exemption. Conditions such as making the results of the research publicly available, public interest, etc. could be considered for this purpose.

Rule 22 - Calling for Information from data fiduciary or intermediary - This rule read with the seventh schedule appears to dilute the data minimisation and purpose limitation provisions provided for in the Act. The wide ambit of powers appears to be in contravention of the Supreme Court judgement in the Puttaswamy case, which places certain restrictions on the government while collecting personal data. This “omnibus” provision flouts guardrails like necessity and proportionality that are important to safeguard the fundamental right to privacy.

It should be clarified whether this rule is merely an enabling provision to facilitate sharing of information, and only designated competent authorities as per law can avail of this provision. Need for Confidentiality

Additionally, the rule mandates that the government may “require the Data Fiduciary or intermediary to not disclose” any request for information made under the Act. There is no requirement of confidentiality indicated in the governing section, i.e. section 36, from which Rule 22 derives its authority. Talking about the avoidance of secrecy in government business, the Supreme Court in the State of U.P. v. Raj Narain, (1975) 4 SCC 428 has held that

“In a government of responsibility like ours, where all the agents of the public must be responsible for their conduct, there can but few secrets. The people of this country have a right to know every public act, everything, that is done in a public way, by their public functionaries. They are entitled to know the particulars of every public transaction in all its bearing. The right to know, which is derived from the concept of freedom of speech, though not absolute, is a factor which should make one wary, when secrecy is claimed for transactions which can, at any rate, have no repercussions on public security (2). To cover with [a] veil [of] secrecy the common routine business, is not in the interest of the public. Such secrecy can seldom be legitimately desired. It is generally desired for the purpose of parties and politics or personal self-interest or bureaucratic routine. The responsibility of officials to explain and to justify their acts is the chief safeguard against oppression and corruption.”

In order to ensure that state interests are also protected, there may be an enabling provision whereby in certain instances confidentiality may be maintained, but there has to be a supervisory mechanism whereby such action may be judged on the anvil of legal propriety.

Education, Epistemologies and AI: Understanding the role of Generative AI in Education

Emotional Contagion: Theorising the Role of Affect in COVID-19 Information Disorder

By incorporating theoretical frameworks from psychology, sociology, and communication studies, we reveal the complex foundations of both the creation and consumption of misinformation. From this research, fear emerged as the predominant emotional driver in both the creation and consumption of misinformation, demonstrating how negative affective responses frequently override rational analysis during crises. Our findings suggest that effective interventions must address these affective dimensions through tailored digital literacy programs, diversified information sources on online platforms, and expanded multimodal misinformation research opportunities in India.

Click to download the research paper

The Cost of Free Basics in India: Does Facebook's 'walled garden' reduce or reinforce digital inequalities?

In 2015, Facebook introduced internet.org in India and it faced a lot of criticism. The programme was relaunched as the Free Basics programme, ostensibly to provide, free of cost, access to the Internet to the economically deprived section of society. The content, i.e. websites, were pre-selected by Facebook and was provided by third-party providers. Later, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) ruled in favor of net neutrality, banning the program in India. A crucial conversation in this debate was also about whether the Free Basics program was going to actually be helpful for those it set out to support.

This paper examines Facebook’s Free Basics programme and its perceived role in bridging digital divides, in the context of India, where it has been widely debated, criticized and finally banned in a ruling from Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI). While the debate on the Free Basics programme has largely been embroiled around the principles of network neutrality, this paper will try to examine it from an ICT4D perspective, embedding the discussion around key development paradigms.

This essay begins by introducing the Free Basics programme in India and the associated proceedings, following which existing literature is reviewed to explore the concept of development, the perceived role of ICT in development, thus laying the scope of this discussion. The essay then examines the question of whether the Free Basics programme reduces or reinforces digital inequality by looking at 3 development paradigms: (1) Construction of knowledge, power structures and virtual colonization in the Free Basics Programme, (2) A sub-internet of the marginalized: looking at second level digital divides and (3) the Capabilities Approach and premise of connectivity as a source of equality and freedom.

The essay concludes with a view that the need for digital access should be viewed as a subset of overall contextual development as opposed to programs unto themselves and taking purely techno-solutionist approaches. There is a requirement for effective needs identification as part of ICT4D research to locate the users at the center and not at the periphery of the discussions. Lastly, policymakers should look into the addressal of more basic concerns like that of access and connectivity and not just on solutions which can be claimed as “quick-wins” in policy implementation.

Mapping the Legal and Regulatory Frameworks of the Ad-Tech Ecosystem in India

In this paper, we try to map the legal and regulatory framework dealing with Advertising Technology (Adtech) in India as well as a few other leading jurisdictions. Our analysis is divided into three main parts, the first being general consumer regulations, which apply to all advertising irrespective of the media – to ensure that advertisements are not false or misleading and do not violate any laws of the country. This part also covers the consumer laws which are specific to malpractices in the technology sector such as Dark Patterns, Influencer based advertising, etc.

The second part of the paper covers data protection laws in India and how they are relevant for the Adtech industry. The Adtech industry requires and is based on the collection and processing of large amounts of data from the users. It is therefore important to discuss the data protection and consent requirements that have been laid out in the spate of recent data protection regulations, which have the potential to severely impact the Adtech industry.

The last part of the paper covers the competition angle of the Adtech industry. Like with social media intermediaries, the Adtech industry in the world is also dominated by two or three players and such a scenario always lends itself easily to anti-competitive practices. It is therefore imperative to examine the competition law framework to see whether the laws as they exist are robust enough to deal with any possible anti competitive practices that may be prevalent in the Adtech sector.

The research was reviewed by Pallavi Bedi, it can be accessed here.