The Centre for Internet and Society’s comments and recommendations to the: Report on AI Governance Guidelines Development

The Centre for Internet & Society (CIS) submitted its comments and recommendations on the Report on AI Governance Guidelines Development.

With research assistance by Anuj Singh

I. Background

On 6 January 2025, a Subcommittee on ‘AI Governance and Guidelines Development’ under the Advisory Group put out the Report on AI Governance Guidelines Development, which advocated for a whole-of-government approach to AI governance. This sub-committee was constituted by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) on November 9, 2023, to analyse gaps and offer recommendations for developing a comprehensive framework for governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As various AI governance conversations take centre stage, this is a welcome step, and we hope that there are more opportunities through public comments and consultations to improve on this important AI document.

CIS’ comments are inline with the submission guidelines, we have provided both comments and suggestions based on the headings and text provided in the report.

II. Governance of AI

The subcommittee report has explained its reasons for staying away from a definition. However, it would be helpful to set the scope of AI, at the outset of the report, given that different AI systems have different roles and functionalities. Having a clearer framework in the beginning can help readers better understand the scope of the conversation in the report. This section also states that AI can now “perform complex tasks without active human control or supervision”, while there are instances where AI is being used without an active human control, there is a need to emphasise on the need for humans in the loop. This has also been highlighted in the OECD AI principles which this report draws inspiration from.

A. AI Governance Principles

A proposed list of AI Governance principles (with their explanations) is given below.

While referring to the OECD AI principles is a good first step in understanding the global best practices, it is suggested that an exercise in mapping of all global AI principles documents published by international and multinationals organisations and civil society is undertaken, to determine principles that are most important for India. The OECD AI principles also come from regions that have a better internet penetration, and higher literacy rate than India, hence for them the principle of “Digital by design governance” would be possible to be achieved but in India, a digital first approach, especially in governance, could lead to large scale exclusions.

B. Considerations to operationalise the principles

1. Examining AI systems using a lifecycle approach

The sub committee has taken a novel approach to define the AI life cycle. The terms “Development, Deployment and Diffusion” have not been seen in any of the major publications about AI lifecycle. While academicians (e.g. Chen et al. (2023), De Silva and Alahakoon (2022)) have pointed out that the AI life cycle contains the following stages - design, development and deployment, others (Ng et al. (2022) have defined it as “data creation, data acquisition, model development, model evaluation and model deployment. Even NASSCOM’s Responsible AI Playbook follows the “conception, designing, development and deployment, as some of the key stages in the AI life cycle. Similarly the OECD also recognised “i) ‘design, data and models’ ii) ‘verification and validation’; iii) ‘deployment’; and iv) ‘operation and monitoring’.” as the phases of the AI life cycle. The subcommittee hence could provide citation as well as a justification of using this novel approach to the AI lifecycle, and state the reason for moving away from the recognised stages. Steering away from an understood approach could cause some confusion amongst different stakeholders who may not be as well versed with AI terminologies and the AI lifecycle to begin with.

2. Taking an ecosystem-view of AI actors

While the report rightly states that multiple actors are involved across the AI lifecycle, it is also important to note that the same actor could also be involved in multiple stages of the AI lifecycle. For example if we take the case of an AI app used for disease diagnosis. The medical professional can be the data principal (using their own data), the data provider (using the app thereby providing the data), and the end user (someone who is using the app for diagnosis). Similarly if we look at the example of a government body, it can be the data provider, the developer (if it is made inhouse or outsourced through tenders), the deployer, as well as the end user. Hence for each AI application there might be multiple actors who play different roles and whose roles might not be static.

While looking at governance approaches, the approach must ideally not be limited to responsibilities and liabilities, especially when the “data principal” and individual end users are highlighted as actors; the approach should also include rights and means of redressal in order to be a rights based people centric approach to AI governance.

3. Leveraging technology for governance

While the use of techno-legal approach in governance is picking up speed there is a need to look at existing Central and State capacity to undertake this, and also look at what are the ways this could affect people who still do not have access to the internet. One example of a techno legal approach that has seen some success has been the Bhumi programme in Andhra Pradesh that used blockchain for land records, however this also led to the weakening of local institutions, and also led to exclusion of marginalised people Kshetri (2021). It was also stated that there was a need to strengthen existing institutions before using a technological measure.

Secondly, while the sub committee has emphasized on the improvements in quality of generative AI tools, there is a need to assess how these tools work for Indian use cases. It was reported last year that ChatGPT could not answer all the questions relating to the Indian civil services exam, and failed to correctly answer questions on geography, however it was able to crack tough exams in the USA. In addition to this, a month ago the Finance Ministry has advised government officials to refrain from using generative AI tools on official devices for fear of leakage of confidential information.

Thirdly, the subcommittee needs to assess India’s data preparedness for this scale of techno legal approach. In our study which was specific to healthcare and AI in India, where we surveyed medical professionals, hospitals and technology companies, a common understanding was that data quality in Indian datasets was an issue, and that there was somewhere reliance on data from the global north. This could be similar in other sectors as well, hence when this data is used to train the system it could lead to harms and biases.

III. GAP ANALYSIS

A. The need to enable effective compliance and enforcement of existing laws.

The sub-committee has highlighted the importance of ensuring that the growth of AI does not lead to unfair trade practices and market dominance. It is hence important to analyse whether the existing laws on antitrust and competition, and the regulatory capacity of Competition Commission of India are robust enough to deal with AI, and the change in technology and technology developers.

There is also an urgent need to assess the issues that might come under the ambit of competition throughout the lifecycle of AI, including in areas of chip manufacturing, compute, data, models and IP. While the players could keep changing in this evolving area of technology there is a need to strengthen the existing regulatory system, before looking at techno legal measures.

We suggest that before a techno legal approach is sought in all forms of governance, there is an urgent need to map the existing regulations both central and state and assess how they apply to regulating AI, and assess the capacity of existing regulatory bodies to regulate issues of AI. In the case of healthcare for example there are multiple laws, policies and guidelines, as well as regulatory bodies that apply to various stages of healthcare and various actors and at times these regulations do not refer to each other or cause duplications that could lead to lack of clarity.

Below we are adding our comments and suggestions certain subsections in this section on The need to enable effective compliance and enforcement of existing laws

1. Intellectual property rights

a. Training models on copyrighted data and liability in case of infringement

While Section. 14 of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957 provides copyright holders with exclusive rights to copy and store works, considering the fact that training AI models involves making non-expressive uses of work, a straightforward conclusion may not be drawn easily. Hence, the presumption that training models on copyrighted data constitutes infringement is premature and unfounded.

This report states “The Indian law permits a very closed list of activities in using copyrighted data without permission that do not constitute an infringement. Accordingly, it is clear that the scope of the exception under Section 52(1)(a)(i) of the Copyright Act, 1957 is extremely narrow. Commercial research is not exempted; not-for-profit 10 institutional research is not exempted. Not-for-profit research for personal or private use, not with the intention of gaining profit and which does not compete with the existing copyrighted work is exempted. “

Indian copyright law follows a ‘hybrid’ model of limitations and exceptions under s.52(1). S. 52(1)(a), which is the ‘fair dealing’ provision, is more open-ended than the rest of the clauses in the section. Specifically, the Indian fair dealing provision permits fair dealing with any work (not being a computer programme) for the purposes of private or personal use, including research.

If India is keen on indigenous AI development, specifically as it relates to foundation models, it should work towards developing frameworks for suitable exceptions ,as may be appropriate. Lawmakers could distinguish between the different types of copyrighted works and public-interest purposes while considering the issue of infringement and liability

b. Copyrightability of work generated by using foundation models

We suggest that a public consultation would certainly be a useful exercise in ensuring opinions and issues of all stakeholders including copyright holders, authors, and users are taken into account.

C. The need for a whole-of-government approach.

While the information existing in silos is a significant issue and roadblock, if the many guidelines and existing principles have taught us anything, it is that without specificity and direct applicability it is difficult for implementers to extrapolate principles into their development, deployment and governance mechanisms. The committee assumes a sectoral understanding from the government on various players in highly regulated sectors such as healthcare or financial services. However, as our recent study on AI in healthcare indicates, there are significant information gaps when it comes to shared understanding of what data is being used for AI development, where the AI models are being developed and what kind of partnerships are being entered into, for development and deployment of AI systems. While the report also highlights the concerns about the siloed regulatory framework, it is also important to consider how the sector specific challenges lend themselves to the cross-sectoral discussion. Consider that an AI credit scoring system in financial services is leading to exclusion errors.

Additionally, consider an AI system being deployed for disease diagnosis. While both use predictive AI, the nature of risk and harm are different. While there can be common and broad frameworks to potentially test efficacy of both AI models, the exact parameters for testing them would have to be unique. Therefore, it will be important to consider where bringing together cross-sectoral stakeholders will be useful and where it may need more deep work at the sector level.

IV. Recommendations

1. To implement a whole-of-government approach to AI Governance, MeitY and the Principal Scientific Adviser should establish an empowered mechanism to coordinate AI Governance.

We would like to reiterate the earlier section and highlight the importance of considering how the sector specific challenges lend themselves to the cross-sectoral discussion. While the whole of government approach is good as it will help building a common understanding between different government institutions, this approach might not be sufficient when it comes to AI governance. It is because this is based on the implicit assumption that internal coordination among various government bodies is enough to manage AI related risks.

2.To develop a systems-level understanding of India’s AI ecosystem, MeitY should establish, and administratively house, a Technical Secretariat to serve as a technical advisory body and coordination focal point for the Committee/ Group.

The Subcommittee report states at this stage, it is not recommended to establish a Committee/ Group or its Secretariat as statutory authorities, as making such a decision requires significant analysis of gaps, requirements, and possible unintended outcomes. While these are valid considerations, it is necessary that there are adequate checks and balances in place. If the secretariat is placed within MeitY then safeguards must be in place to ensure that officials have autonomy in decision making. The subcommittee suggests that MeitY can bring officials on deputation from other departments. Similarly the committee proposes bringing experts from the industry, while it is important for informed policy making, there is also risk of regulatory capture. Setting a cap on the percentage of industry representatives and full disclosure of affiliations of experts involved are some of the safeguards which can be considered. We also suggest that members of civil society are also considered for this Secretariat.

3.To build evidence on actual risks and to inform harm mitigation, the Technical Secretariat should establish, house, and operate an AI incident database as a repository of problems experienced in the real world that should guide responses to mitigate or avoid repeated bad outcomes.

The report suggests that the technical secretariat will develop an actual incidence of AI-related risks in India. In most instances, an AI incident database will assume that an AI related unfavorable incident has already taken place, which then implies that it's no longer a potential risk but an actual harm. This recommendation takes a post-facto approach to assessing AI systems, as opposed to conducting risk assessments prior to the actual deployment of an AI system. Further, it also lays emphasis on receiving reports from public sector organizations deploying AI systems. Given that public sector organizations, in many cases, would be the deployers of AI systems as opposed to the developers, they may have limited know-how on functionality of tools and therefore the risks and harms.

It is important to clarify and define what will be considered as an AI risk as this could also depend on stakeholders, for example losing clients due to an AI system for a company is a risk, and so is an individual being denied health insurance because of AI bias. With this understanding, while there is a need to keep an active assessment of risks and the emergence of new risks, the Technical Secretariat could also undergo a mapping of the existing risks which have been highlighted by academia and civil society and international organisations and begin the risk database with that. In addition, the “AI incident database” should also be open to research institutions and civil society organisations similar to The OECD AI Incidents Monitor.

4. To enhance transparency and governance across the AI ecosystem, the Technical Secretariat should engage the industry to drive voluntary commitments on transparency across the overall AI ecosystem and on baseline commitments for high capability/widely deployed systems.

It is commendable that the sub committee in this report extends the transparency requirement to the government, with the example of law enforcement. This would create more trust in the systems and also add the responsibility on the companies providing these services to be compliant with existing laws and regulations.

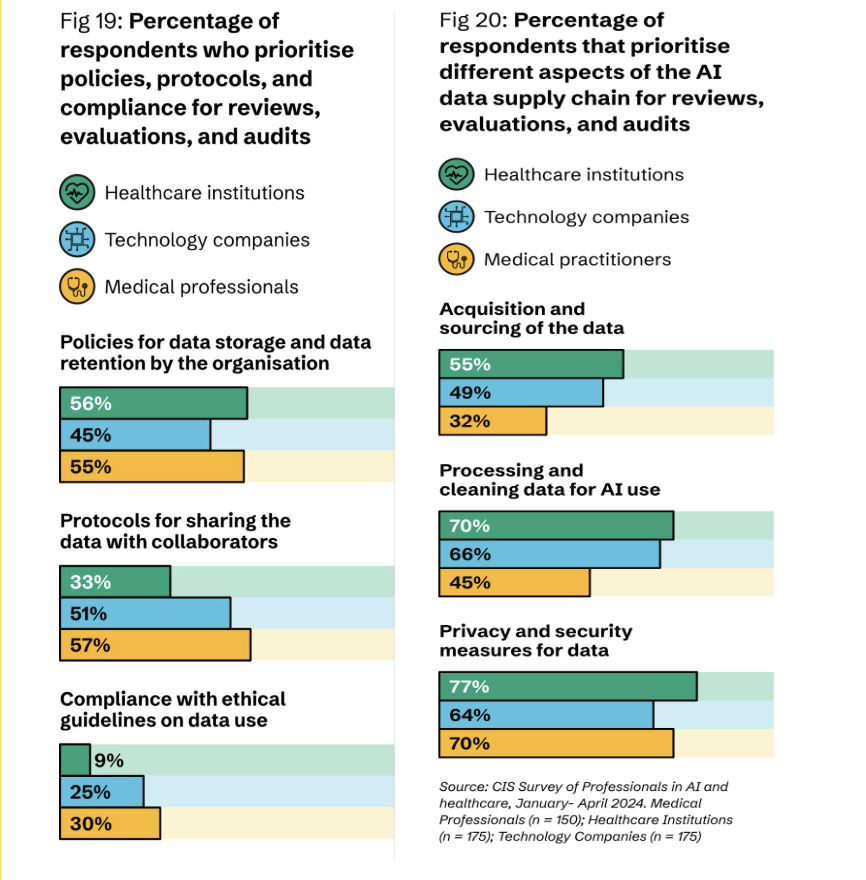

While the transparency measures listed will ensure better understanding of processes of AI developers and deployers, there is also a need to bring in responsibility along with transparency. While this report also mentions ‘peer review by third parties’, we would also like to suggest auditing as a mechanism to undertake transparency and responsibility. In our study on AI data supply chain & auditability and healthcare in India, (which surveyed 150 medical professionals, 175 respondents from healthcare institutions and 175 respondents from technology companies); revealed that 77 percent of healthcare institutions and 64 percent of the technology companies surveyed for this study, conducted audits or evaluations of the privacy and security measures for data.

5. Form a sub-group to work with MEITY to suggest specific measures that may be considered under the proposed legislation like Digital India Act (DIA) to strengthen and harmonise the legal framework, regulatory and technical capacity and the adjudicatory set-up for the digital industries to ensure effective grievance redressal and ease of doing business.

It would be necessary to provide some clarity on where the process to the Digital India Act is currently. While there were public consultations in 2023, we have not heard about the progress in the development of the Act. The most recent discussion on the Act was in January 2025, where S Krishnan, Secretary, Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY), stated that they were in no hurry to carry forward the draft Digital India Act and regulatory framework around AI. He also stated that the existing legal frameworks were currently sufficient to handle AI intermediaries.

We would also like to highlight that during the consultations on the DIA it was proposed to replace the Information Technology Act 2000. It is necessary that the subcommittee give clarity on this, since if the DIA is enacted, this reports section III on GAP analysis especially around the IT Act, and Cyber Security will need to be revisited.