Internet Governance Blog

- Using information from court orders, user reports, and government orders, and running network tests from six ISPs, Kushagra Singh, Gurshabad Grover and Varun Bansal presented the largest study of web blocking in India. Through their work, they demonstrated that major ISPs in India use different techniques to block websites, and that they don’t block the same websites (link).

- Gurshabad Grover and Kushagra Singh collaborated with Simone Basso of the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) to study HTTPS traffic blocking in India by running experiments on the networks of three popular Indian ISPs: ACT Fibernet, Bharti Airtel, and Reliance Jio (link).

- For The Leaflet, Torsha Sarkar and Gurshabad Grover wrote about the legal framework of blocking in India — Section 69A of the IT Act and its rules. They considered commentator opinions questioning the constitutionality of the regime, whether originators of content are entitled to a hearing, and whether Rule 16, which mandates confidentiality of content takedown requests received by intermediaries from the Government, continues to be operative (link).

- In the Hindustan Times, Gurshabad Grover critically analysed the confidentiality requirement embedded within Section 69A of the IT Act and argued how this leads to internet users in India experiencing arbitrary censorship (link).

- Torsha Sarkar, along with Sarvjeet Singh of the Centre for Communication Governance (CCG), spoke to Medianama delineating the procedural aspects of section 69A of the IT Act (link).

- Arindrajit Basu spoke to the Times of India about the geopolitical and regulatory implications of the Indian government’s move to ban fifty-nine Chinese applications from India (link).

-

Amber Sinha dissects the Puttaswamy Judgment through an analysis of the sources, scope and structure of the right, and its possible limitations. [link]

-

Through a visual guide to the fundamental right to privacy, Amber Sinha and Pooja Saxena trace how courts in India have viewed the right to privacy since Independence, explain how key legal questions were resolved in the Puttaswamy Judgement, and provide an account of the four dimensions of privacy — space, body, information and choice — recognized by the Supreme Court. [link]

-

Based on publicly available submissions, press statements, and other media reports, Arindrajit Basu and Amber Sinha track the political evolution of the data protection ecosystem in India, on EPW Engage. They discuss how this has, and will continue to impact legislative and policy developments. [link]

-

For the AI Policy Exchange, Arindrajit Basu and Siddharth Sonkar examine the Automated Facial Recognition Systems (AFRS), and define the key legal and policy questions related to privacy concerns around the adoption of AFRS by governments around the world. [link]

-

Over the past decade, reproductive health programmes in India have been digitising extensive data about pregnant women. In partnership with Privacy International, we studied the Mother and Child Tracking system (MCTS), and Ambika Tandon presents the impact on the privacy of mothers and children in the country. [link]

-

While the right to privacy can be used to protect oneself from state surveillance, Mira Swaminathan and Shubhika Saluja write about the equally crucial problem of lateral surveillance — surveillance that happens between individuals, and within neighbourhoods, and communities — with a focus on this issue during the COVID-19 crisis. [link]

-

Finally, take a dive into the archives of the Centre for Internet and Society to read our work, which was cited in the Puttaswamy judgment — essays by Ashna Ashesh, Vidushi Marda and Bhairav Acharya that displaced the notion that privacy is inherently a Western concept, by attempting to locate the constructs of privacy in Classical Hindu [link], and Islamic Laws [link]; and Acharya’s article in the Economic and Political Weekly, which highlighted the need for privacy jurisprudence to reflect theoretical clarity, and be sensitive to unique Indian contexts [link].

A Guide to Drafting Privacy Policy under the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, (PDP Bill) which is currently being deliberated by the Joint Parliamentary Committee, is likely to be tabled in the Parliament during the winter session of 2021.

Media Market Risk Ratings: India

The Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) and the Global Disinformation Index (GDI) are launching a study into the risk of disinformation on digital news platforms in India, creating an index that is intended to serve donors and brands with a neutral assessment of news sites that they can utilise to defund disinformation.

Beyond the PDP Bill: Governance Choices for the DPA

This article examines the specific governance choices the Data Protection Authority (DPA) in India must deliberate on vis-à-vis its standard-setting function, which are distinct from those it will encounter as part of its enforcement and supervision functions.

Big Tech’s privacy promise to consumers could be good news — and also bad news

Rajat Kathuria, Isha Suri write: Its use as a tool for market development must balance consumer protection, innovation, and competition.

UN Questionnaire on Digital Innovation, Technologies and Right to Health

The Centre for Internet & Society (CIS) contributed to the questionnaire put out by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, on digital innovation, technologies and the right to health. The responses were authored by Pahlavi and Shweta Mohandas, and edited by Indumathi Manohar.

The PDP Bill 2019 Through the Lens of Privacy by Design

This paper evaluates the PDP Bill based on the Privacy by Design approach. It examines the implications of Bill in terms of the data ecosystem it may lead to, and the visual interface design in digital platforms. This paper focuses on the notice and consent communication suggested by the Bill, and the role and accountability of design in its interpretation.

The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing: Demanding your Data

The increasing digitalization of the economy and ubiquity of the Internet, coupled with developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) has given rise to transformational business models across several sectors.

Reclaiming AI Futures: Call for Contributions and Provocations

CIS is pleased to share this call for contributions by Mozilla Fellow Divij Joshi. CIS will be working with Divij to edit, collate, and finalise this publication. This publication will add to Divij’s work as part of the AI observatory. The work is entirely funded by Divij Joshi.

Comments to National Digital Health Mission: Health Data Management Policy

CIS has submitted comments to the National Health Data Management Policy. We welcome the opportunity provided to our comments on the Policy and we hope that the final Policy will consider the interests of all the stakeholders to ensure that it protects the privacy of the individual while encouraging a digital health ecosystem.

Mapping Web Censorship & Net Neutrality Violations

For over a year, researchers at the Centre for Internet and Society have been studying website blocking by internet service providers (ISPs) in India. We have learned that major ISPs don’t always block the same websites, and also use different blocking techniques. To take this study further, and map net neutrality violations by ISPs, we need your help. We have developed CensorWatch, a research tool to collect empirical evidence about what websites are blocked by Indian ISPs, and which blocking methods are being used to do so. Read more about this project (link), download CensorWatch (link), and help determine if ISPs are complying with India’s net neutrality regulations.

Fundamental Right to Privacy — Three Years of the Puttaswamy Judgment

Today marks three years since the Supreme Court of India recognised the fundamental right to privacy, but the ideals laid down in the Puttaswamy Judgment are far from being completely realized. Through our research, we invite you to better understand the judgment and its implications, and take stock of recent issues pertaining to privacy.

Comments on NITI AAYOG Working Document: Towards Responsible #AIforAll

The NITI Aayog Working Document on Responsible AI for All released on 21st July 2020 serves as a significant statement of intent from NITI Aayog, acknowledging the need to ensure that any conception of “Responsible AI” must fulfill constitutional responsibilities, incorporated through workable principles. However, as it is a draft document for discussion, it is important to highlight next steps for research and policy levers to build upon this report.

Investigating TLS blocking in India

A study into Transport Layer Security (TLS)-based blocking by three popular Indian ISPs: ACT Fibernet, Bharti Airtel and Reliance Jio.

Towards Algorithmic Transparency

This policy brief examines the issue of transparency as a key ethical component in the development, deployment, and use of Artificial Intelligence.

After the Lockdown

This post was first published in the Business Standard, on April 2, 2020.

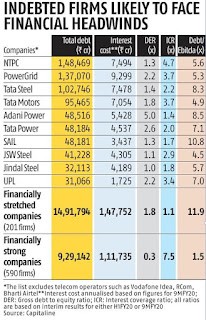

Source: Krishna Kant: "Coronavirus shutdown puts Rs 15-trillion debt at risk, to impact finances", BS, March 30, 2020:

For the longer term, a fundamental reconsideration for allocating resources is needed through coherent, orchestrated policy planning and support. What the government can do as a primary responsibility, besides ensuring law and order and security, is to develop our inadequate and unreliable infrastructure, including facilities and services that enable efficient production clusters, their integrated functioning, and skilling. For instance, Apple’s recent decision against moving iPhone production from China to India was reportedly because similar large facilities (factories of 250,000) are not feasible here, and second, our logistics are inadequate. Such considerations should be factored into our planning, although Apple may well have to revisit the very sustainability of the concept of outsize facilities that require the sort of repressive conditions prevailing in China. However, we need not aim for building unsustainable mega-factories. Instead, a more practical approach may be to plan for building agglomerations of smaller, sustainable units, that can aggregate their activity and output effectively and efficiently. Such developments could form the basis of numerous viable clusters, and where possible, capitalise on existing incipient clusters of activities. Such infrastructure needs to be extended to the countryside for agriculture and allied activities as well, so that productivity increases with a change from rain-fed, extensive cultivation to intensive practices, with more controlled conditions.

The automotive industry, the largest employer in manufacturing, provides an example for other sectors. It was a success story like telecom until recently, but is now floundering, partly because of inappropriate policies, despite its systematic efforts at incorporating collaborative planning and working with the government. It has achieved the remarkable transformation of moving from BS-IV to BS-VI emission regulations in just three years, upgrading by two levels with an investment of Rs 70,000 crore, whereas European companies have taken five to six years to upgrade by one level. This has meant that there was no time for local sourcing, and therefore heavy reliance on global suppliers, including China. While the collaborative planning model adopted by the industry provides a model for other sectors, the question here is, what now. In a sense, it was not just the radical change in market demand with the advent of ridesharing and e-vehicles, but also the government’s approach to policies and taxation that aggravated its difficulties.

India’s ‘Self-Goal’ in Telecom

This post was first published in the Business Standard, on March 5, 2020.

The government apparently cannot resolve the problems in telecommunications. Why? Because the authorities are trying to balance the Supreme Court order on Adjusted Gross Revenue (AGR), with keeping the telecom sector healthy, while safeguarding consumer interest. These irreconcilable differences have arisen because both the United Progressive Alliance and the National Democratic Alliance governments prosecuted unreasonable claims for 15 years, despite adverse rulings! This imagined “impossible trinity” is an entirely self-created conflation.

If only the authorities focused on what they can do for India’s real needs instead of tilting at windmills, we’d fare better. Now, we are close to a collapse in communications that would impede many sectors, compound the problem of non-performing assets (NPAs), demoralise bankers, increase unemployment, and reduce investment, adding to our economic and social problems.

Is resolving the telecom crisis central to the public interest? Yes, because people need good infrastructure to use time, money, material, and mindshare effectively and efficiently, with minimal degradation of their environment, whether for productive purposes or for leisure. Systems that deliver water, sanitation, energy, transport and communications support all these activities. Nothing matches the transformation brought about by communications in India from 2004 to 2011 in our complex socio-economic terrain and demography. Its potential is still vast, limited only by our imagination and capacity for convergent action. Yet, the government’s dysfunctional approach to communications is in stark contrast to the constructive approach to make rail operations viable for private operators.

India’s interests are best served if people get the services they need for productivity and wellbeing with ease, at reasonable prices. This is why it is important for government and people to understand and work towards establishing good infrastructure.

What the Government Can Do

An absolute prerequisite is for all branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), the press and media, and society, to recognise that all of us must strive together to conceptualise and achieve good infrastructure. It is not “somebody else’s job”, and certainly not just the Department of Telecommunications’ (DoT’s). The latter cannot do it alone, or even take the lead, because the steps required far exceed its ambit.

Act Quickly

These actions are needed immediately:

First, annul the AGR demand using whatever legal means are available. For instance, the operators could file an appeal, and the government could settle out of court, renouncing the suit, accepting the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) ruling of 2015 on AGR.

Second, issue an appropriate ordinance that rescinds all extended claims. Follow up with the requisite legislation, working across political lines for consensus in the national interest.

Third, take action to organise and deliver communications services effectively and efficiently to as many people as possible. The following steps will help build and maintain more extensive networks with good services, reasonable prices, and more government revenues.

Enable Spectrum Usage on Feasible Terms

Wireless regulations

It is infeasible for fibre or cable to reach most people in India, compared with wireless alternatives. Realistically, the extension of connectivity beyond the nearest fibre termination point is through wireless middle-mile connections, and Wi-Fi for most last-mile links. The technology is available, and administrative decisions together with appropriate legislation can enable the use of spectrum immediately in 60GHz, 70-80GHz, and below 700MHz bands to be used by authorised operators for wireless connectivity. The first two bands are useful for high-capacity short and medium distance hops, while the third is for up to 10 km hops. The DoT can follow its own precedent set in October 2018 for 5GHz for Wi-Fi, i.e., use the US Federal Communications Commission regulations as a model.1 The one change needed is an adaptation to our circumstances that restricts their use to authorised operators for the middle-mile instead of open access, because of the spectrum payments made by operators. Policies in the public interest allowing spectrum use without auctions do not contravene Supreme Court orders.

Policies: Revenue sharing for spectrum

A second requirement is for all licensed spectrum to be paid for as a share of revenues based on usage as for licence fees, in lieu of auction payments. Legislation to this effect can ensure that spectrum for communications is either paid through revenue sharing for actual use, or is open access for all Wi-Fi bands. The restricted middle-mile use mentioned above can be charged at minimal administrative costs for management through geo-location databases to avoid interference. In the past, revenue-sharing has earned much more than up-front fees in India, and rejuvenated communications.2 There are two additional reasons for revenue sharing. One is the need to manufacture a significant proportion of equipment with Indian IPR or value-added, to not have to rely as much as we do on imports. This is critical for achieving a better balance-of-payments, and for strategic considerations. The second is to enable local talent to design and develop solutions for devices for local as well as global markets, which is denied because it is virtually impossible for them to access spectrum, no matter what the stated policies might claim.

Policies and Organisation for Infrastructure Sharing

Further, the government needs to actively facilitate shared infrastructure with policies and legislation. One way is through consortiums for network development and management, charging for usage by authorised operators. At least two consortiums that provide access for a fee, with government’s minority participation in both for security and the public interest, can ensure competition for quality and pricing. Authorised service providers could pay according to usage.

Press reports of a consortium approach to 5G where operators pay as before and the government “contributes” spectrum reflect seriously flawed thinking.3 Such extractive payments with no funds left for network development and service provision only support an illusion that genuine efforts are being made to the ill-informed, who simultaneously rejoice in the idea of free services while acclaiming high government charges (the two are obviously not compatible).

Instead of tilting at windmills that do not serve people’s needs while beggaring their prospects, commitment to our collective interests requires implementing what can be done with competence and integrity.

Shyam (no space) Ponappa at gmail dot com

1. https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/2018_10_29%20DCC.pdf

2. http://organizing-india.blogspot.in/2016/04/ breakthroughs- needed-for-digital-india.html

3. https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/govt-considering-spv-with-5g-sweetener-as-solution-to-telecom-crisis-120012300302_1.html

‘Future of Work’ in India’s IT/IT-es Sector

The Centre for Internet and Society has recently undertaken research into the impact of Industry 4.0 on work in India. Industry 4.0, for the purposes of the research, is conceptualised as the technical integration of cyber physical systems (CPS) into production and logistics and the use of the ‘internet of things’ (connection between everyday objects) and services in (industrial) processes. By undertaking this research, CIS seeks to complement and contribute to the discourse and debates in India around the impact of Industry 4.0. In furtherance of the same, this report seeks to explore several key themes underpinning the impact of Industry 4.0 specifically in the IT/IT-es sector and broadly on the nature of work itself.

RBI Ban on Cryptocurrencies not backed by any data or statistics

In March 2020, the Supreme Court of India quashed the RBI order passed in 2018 that banned financial services firms from trading in virtual currency or cryptocurrency. Keeping this policy window in mind, the Centre for Internet & Society will be releasing a series of blog posts and policy briefs on cryptocurrency regulation in India

Cryptocurrency Regulation in India – A brief history

In March 2020, the Supreme Court of India quashed the RBI order passed in 2018 that banned financial services firms from trading in virtual currency or cryptocurrency. Keeping this policy window in mind, the Centre for Internet & Society will be releasing a series of blog posts and policy briefs on cryptocurrency regulation in India

A Compilation of Research on the PDP Bill

The most recent step in India’s initiative to create an effective and comprehensive Data Protection regime was the call for comments to the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, which closed last month. Leading up to the comments, CIS has published numerous research pieces with the goal of providing a comprehensive overview of how this legislation would place India within the global scheme, and how the local situation has developed, as well as analysing its impacts on citizens’ rights.