This is a time when, as

the authorities deal with a lockdown, there needs to be an equal

emphasis on providing for large numbers of people without the money for

food and necessities, while the rest of us wait it out. Hard as it is,

an MIT scholar writes that after the Spanish flu in 1918, cities that

restricted public gatherings sooner and longer had fewer fatalities, and

emerged with stronger economic growth.

1 It

is likely that costs and benefits vary with economic and social

capacity, and we may have a harder time with it here. Going forward,

government action to help provide relief, rehabilitate people and deal

with loss needs to be well planned, including targeting aid to the urban

and displaced poor.

2

As important now as to

ensure the lockdown continues is to plan on how to revive productive

activity and the economy, and restore public confidence. A systematic

approach will likely yield better results.

A major element of the

recovery plan is steps such as liberal credit and amortisation terms,

perhaps much more than the three-month extension the Reserve Bank of

India (RBI) has announced. A primary purpose is the re-initiation of

large-scale activities such as construction, of which there are

reportedly about 200,000 large projects around the country. These have

to be nursed back to being going concerns. The RBI may need to consider

doing more, including lowering rates.

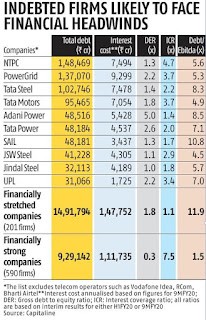

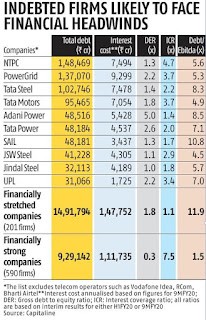

An ominous development

that has grown as the economy slowed is financial stress that could

swell non-performing assets (NPAs). At the half-year ending September

2019, about half of non-financial large corporations in India, excluding

telecom, showed financial stress (see table).

Source: Krishna Kant: "Coronavirus shutdown puts Rs 15-trillion debt at risk, to impact finances", BS, March 30, 2020:

These include some of

India’s largest companies, producing power, steel, and chemicals. The

201 companies have total debt of nearly Rs 15 trillion, more than half

of all borrowings. There is also the debt overhang of the National

Highways Authority of India, and of the telecom companies. Ironically,

the telecom companies are our lifeline now, despite having nearly

collapsed under debt because of ill-advised policies in the past, which

have still not changed. Perhaps our obvious dependence telecom services

now will spark well conceived, convergent policies for this sector, so that we can function effectively.

A start with immediate

changes in administrative rules for 60GHz, 70-80GHz, and 500-700MHz

wireless use, modelled on the US FCC regulations as was done for the

5GHz Wi-Fi in October 2018, could change the game. It will provide the

opportunity in India for the innovation of devices, their production,

and use, possibly unleashing this sector. This can help offset our

reliance on imported technology and equipment. However, such changes in

policies and purchasing support have eluded us thus far. Now, the only

way our high-technology manufacturers can thrive is to succeed

internationally, in order to be able to sell to the domestic market.

Imagine how hard that might be, and you begin to get an inkling of why

we have few domestic product champions, struggling against odds in areas

such as optical switches, networking equipment, and wireless devices.

For order-of-magnitude change, however, structural changes need to be

worked out in consultation with operators in the organisation of

services through shared infrastructure.

For the longer term, a fundamental

reconsideration for allocating resources is needed through coherent,

orchestrated policy planning and support. What the government can do as a

primary responsibility, besides ensuring law and order and security, is

to develop our inadequate and unreliable infrastructure, including

facilities and services that enable efficient production clusters, their

integrated functioning, and skilling. For instance, Apple’s recent

decision against moving iPhone production

from China to India was reportedly because similar large facilities

(factories of 250,000) are not feasible here, and second, our logistics

are inadequate. Such considerations should be factored into our

planning, although Apple may well have to revisit the very

sustainability of the concept of outsize facilities that require the

sort of repressive conditions prevailing in China. However, we need not

aim for building unsustainable mega-factories. Instead, a more practical

approach may be to plan for building agglomerations of smaller,

sustainable units, that can aggregate their activity and output

effectively and efficiently. Such developments could form the basis of

numerous viable clusters, and where possible, capitalise on existing

incipient clusters of activities. Such infrastructure needs to be

extended to the countryside for agriculture and allied activities as

well, so that productivity increases with a change from rain-fed,

extensive cultivation to intensive practices, with more controlled

conditions.

The automotive industry,

the largest employer in manufacturing, provides an example for other

sectors. It was a success story like telecom until recently, but is now

floundering, partly because of inappropriate policies, despite its

systematic efforts at incorporating collaborative planning and working

with the government. It has achieved the remarkable transformation of

moving from BS-IV to BS-VI emission regulations in just three years,

upgrading by two levels with an investment of Rs 70,000 crore, whereas

European companies have taken five to six years to upgrade by one level.

This has meant that there was no time for local sourcing, and therefore

heavy reliance on global suppliers, including China. While the

collaborative planning model adopted by the industry provides a model

for other sectors, the question here is, what now. In a sense, it was

not just the radical change in market demand with the advent of

ridesharing and e-vehicles, but also the government’s approach to

policies and taxation that aggravated its difficulties.

Going forward, policies

that are more congruent in terms of societal goals, including employment

that support the development of large manufacturing opportunities, need

to be thought through from a perspective of aligning and integrating

objectives (in this case, transportation). Areas such as automotive and

other industries for the manufacture of road and rail transport vehicles

need to be considered from the perspective of reconfiguring the

purpose, flow, and value-added, to achieve both low-cost, accessible

mass transport, and vehicles for private use that complement

transportation objectives as also employment and welfare.

Systematic and convergent planning and implementation across sectors could help achieve a better revival.

Shyam (no space) Ponappa at gmail dot com