Recapturing the Commons

Regulations that facilitate infrastructure with appropriate public resource use will enhance productivity.

The article was published in Business Standard on March 7, 2019 and in Organizing India Blogspot on March 8, 2019.

Growth in the third quarter was disappointing, but there are signs of a cyclical recovery, with a Purchasing Managers Index for manufacturing at a 14-month high. For a significant upward shift of our growth curve, however, apart from lower interest rates, policy-makers have to be constructive. What might we wish for? Here are some suggestions.

Accept the reality that investible funds in India are insufficient for our needs. These include our stock and net inflow of capital, and profits available for investment. We can try to increase our productive capacity or choose business-as-usual, thereby staying below our potential. Why? Because our activities aren’t profitable enough to induce and sustain investment. We need investment —in hard infrastructure, such as transportation and logistics, electricity, water and sewerage, and communications, and in second-order infrastructure, such as security and law and order, health care, education and training, banking, finance and insurance. There’s also the need for reorganisation of markets and practices, e.g., in agriculture, infrastructure, and government procurement.

There’s little doubt that digital connectivity is invaluable for all these. While the imperative is clear, the question is how to orchestrate achieving the desired results.

The telecom operators, alas, have low profitability, inadequate network coverage, and too much debt. Continuing as before means subpar access and productivity for all. We are all hamstrung, and even more so in rural areas. Because of the expanse an7d scattered users there, connectivity entails much higher costs with lower revenue potential.

Self-Organising Infrastructure – A Conceptual Flaw Without Regulatory Support

Meanwhile, there are conceptual flaws in our approach. The National Optical Fibre Network (Bharat Broadband Network Limited or BharatNet) was conceived as a countrywide fibre backbone. The plan was for optical fibre links to 250,000 gram panchayat villages covering India’s approximately 600,000 inhabited villages. A major assumption, however, was that private operators would build access networks to villages and to users. This was unrealistic for a number of reasons. First, there’s the cost of covering sparse users over large expanses with low revenue potential. Second, the supportive regulations for wireless technologies to build the access networks were/are not in place. For example, even for the established 5 GHz WiFi range used globally for WiFi hotspots, restrictive policies meant that 5 GHz equipment could not be used effectively in India in urban or rural installations. This changed with new regulations for 5 GHz, but only four months ago in October 2018 (for details see https://organizing-india.blogspot.com/2018/11/a-great-start-on-wi-fi-reforms.html).

Other wireless technologies for intermediate- and last-mile links are still blocked, and need enabling regulations.

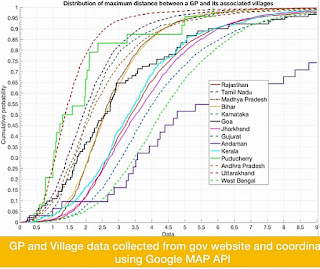

- The 700 MHz band: No operators bid for this given its high price, although it is very useful for covering distances of 5-10 km, and can penetrate walls and foliage. This band together with the 500 and 600 MHz bands could be used to connect gram panchayats to nearby villages. A study of inter-site distances in 14 states shows that most villages would be covered with this range (see Chart below).

Study of Inter Site Distances - Gram Panchayats and Villages

- The 500 and 600 MHz bands are allocated for TV, and therefore are part of the “tragedy of the unused commons”. Only a small fraction is used for broadcasting in India because of limited free-to-air TV and better alternatives. As they are earmarked for broadcasting, they are not used for telephony either.

- The 70-80 GHz band (E-band) is effective for short-range links covering more users at 3-4 km, but not permitted in India, although it is light-licensed in many countries with nominal fees, e.g., the USA, UK, Russia, and Australia. While ideally our regulations should align with global norms, there are exorbitant charges on operators (reportedly 37 per cent, plus corporate taxes), a debt overhang from spectrum auctions, huge investment needs, and relatively low revenue potential. Compelling arguments to let operators use the E-band with unlicensed access, with registry on a geo-location database to manage interference, to be reviewed after some years. The additional traffic will generate revenues from which government collections will increase.

- The 60 GHz (V-band for distances up to 1.6 km): the Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI) opposes making it licence-free as in most countries, and wants it assigned to operators for access and backhaul. For the same reasons as for E-band, operators could be allowed unlicensed access, with a review after some years.

Market Structure and Organisation

A larger problem is that legacy structural and organisational issues need concerted efforts to take requisite policy initiatives. This is perhaps a greater, more urgent need for ubiquitous connectivity.

Successive governments have struggled with revival plans for BSNL and MTNL, somewhat analogous to Air India and Indian Airlines in aviation. Governments have not provided sustained support for ambitious connectivity objectives. There is sometimes inadequate understanding of fast-changing, technically complex enterprises, and episodic attention is given to large enterprises that need timely capital- and skill-intensive decisions (and decision-makers in place), and the upgrading of skills and operating practices. BSNL and MTNL are declining, with bailouts, market disruption through price-cutting, and inability to deliver profits. This is a huge opportunity cost on citizens. However, it is conceivable that with appropriate leadership, and organisational and capital backing, these enterprises could contribute effectively to ubiquitous connectivity, rather than being a drag and/or a disruptive factor. This could happen, for instance, if an alliance were possible with private sector operators providing leadership, organisation and capital, while state ownership concentrates on safeguarding the public interest.

Bharti Enterprises’ Chairman Sunil Mittal has suggested an alliance with Vodafone for an optical fibre network. Bharti and Vodafone already have a joint venture, Indus Towers, providing passive infrastructure services to operators. If regulations enabled active infrastructure from a consortium including BSNL and MTNL, it would leverage the infrastructure while reducing the capital requirements, and increase delivery capability. The entire thrust of regulations could be oriented to facilitating service delivery, leveraging capital, equipment and human resources.

The regulatory approach should aim to facilitate access equitably to public resources that belong to citizens, and not to create obstacles.