'What Security Breach?' The Unchanging Tone of UIDAI's Denials

This week brought with it another instance of Aadhaar déjà vu. The narrative is now eerily familiar to people with even a passing acquaintance with the matter.

The article by Karan Saini was published in the Wire on September 12, 2018

A security vulnerability in the Aadhaar ecosystem comes to light, usually through civil society stakeholders or the media. The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) issues a standard denial, refuses to publicly acknowledge that it has to course-correct and fix the problem, and the public waits for the process to repeat.

Following a three-month-long investigation by Huffington Post into the known and documented problem of cracked Aadhaar enrolment software, several security experts from within the country and elsewhere were able to conclude that the authenticity of entries within the Aadhaar database was likely compromised to an unknown extent. This was a direct result of a patched version of the enrolment software with stripped security features being circulated and used by potential hostile actors – among others.

The patched software bypasses several crucial security features of the enrolment client and could have also been used to get around the biometric authentication which legitimate enrolment operators would have to undertake before attempting to add new entries to the database.

The UIDAI responded to this report with a statement which is nearly identical to many of the authority’s previous press releases on alleged security incidents.

In its statement, the UIDAI said that “the claims made in the report about Aadhaar being vulnerable to tampering leading to ghost entries in Aadhaar database by purportedly bypassing operators’ biometric authentication to generate multiple Aadhaar cards is totally baseless”.

The statement which was issued by the authority seems straightforward but is actually cryptic in its very nature. The story published by Huffington Post did not categorically assert that the software bypass was being used ‘to generate multiple Aadhaar cards’, while the authority’s statement specifically refuted this claim.

This is, sadly, not new. The Aadhaar authority has always purposely misinterpreted what is actually being alleged in critical stories, and then presented their interpretations in their statements of rebuttal, which essentially amount to irresponsible dissemination of misleading information.

For instance, the UIDAI ignores that even without the issue of cracked enrolment software, there are already many proven cases of ghost entries in the database, including that of a Pakistani ISI spy as well as an Uzbek national involved in illegal sex-trade in the country. Both of these persons held real, valid Aadhaar cards which were issued to them under false identities.

The UIDAI also states that enrolments are verified at their backend system in order to prevent any such false entries from finding their way into the database. Given this, the question arises – how did these highlighted cases of false entries make it through the supposed checks and balances in place to the point where Aadhaar numbers for these persons were issued (and delivered)?

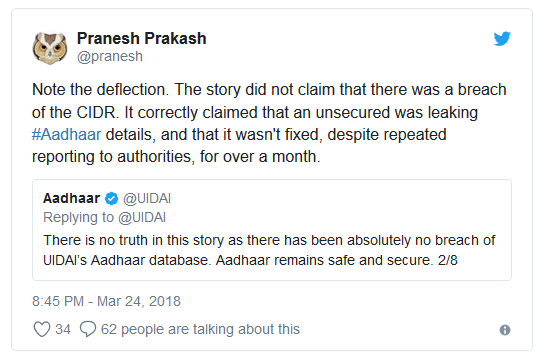

Similar events took place when in March 2018, ZDNet broke the story of an application programming interface (API) hosted on the website of utility provider Indane Gas, which could have been abused by hackers to steal information such as full names, Aadhaar numbers, names of linked banking institutions as well as details of the specific utility provider which a person uses for a major chunk of the population.

The UIDAI statement at the time baldly claimed that there was no breach of its central database (what is called the ‘CIDR’) and that biometric data were safe. The only problem? Neither of these issues were asserted or even hinted at in the original story.

Reporters from the publication had attempted to reach out to UIDAI repeatedly – and that too through several mediums of communication, such as phone, email and even direct messages to the official UIDAI Twitter account – all to no avail.

“We tried to contact UIDAI by phone and email after we learned of the Aadhaar data leak. We eventually sent all the details in a Twitter DM message — but only because UIDAI wouldn’t offer […] an email address to send this data leak issue to,” posted Zack Whittaker, the reporter who had broken the story for ZDNet, as a tweet on his public Twitter account.

This was not the first time the authority had done such a thing (and neither was it the last, as we see with the Huffington Post story), as witnessed in the January 2018 incident with the Tribune; where the UIDAI did not respond to the paper’s attempts at communication at all before publication and later used it to state that no security incident had taken place altogether.

Reporters from the Huffington Post had also attempted to reach out to UIDAI prior to publication of the story; attempts at communication which the UIDAI willingly left unanswered. After UIDAI’s rebuttal, the Huffington Post published a statement of their own in which they asserted that they stood by the claims made in their story, while also making it known that the UIDAI had never responded directly to any of their communication.

The UIDAI’s most recent statement deploys a bizarre array of security jargon including buzzwords such as “full encryption”, “access control” and “tamper resistance” – without providing any elaboration on what any of these things would help prevent with regard to the issues raised in the media report.

This obfuscation is very troubling, and particularly so for those people who do not actively follow news regarding the troubles of the programme or other media organisations that are not equipped to understand the nuances of security reporting. For both groups of people, the statements issued by the UIDAI would be enough of an assertion to lead them to believe that all is well with the project and that anyone saying otherwise is an “unscrupulous element” with “vested interests”.

After the first few incidents, the authority’s cookie-cutter response seems to be part of the playbook through which they seek to protect their image: by retaining the ability to publicly deny an incident, even if it has already taken place; which is done by never confirming (or even acknowledging) an issue before publication. This is presumably done out of fear of the reputational damage which would inevitably be caused by admittance of a compromise or fault on their part.

Consider what happened with the Tribune breach report. The UIDAI officially denied it (even though some of their lower-level officials were quoted in the story), filed an FIR against the journalist. When the dust settled down, a prominent business newspaper ran a story which strangely enough quoted anonymous officials who highlighted the steps that were taken to fix the problem.

The UIDAI understands that ‘the first step in solving a problem is to recognise that it does exist’. Acknowledging problems within the Aadhaar project would be catastrophically damaging for the authority as well as the public’s perception of them. This is why we are always presented with almost indistinguishable statements of rebuttal and denial from the UIDAI, which too are never backed with any evidence.

Seeing as how the UIDAI’s statements almost always end up backfiring, their decision to employ a social media agency to monitor the internet for chatter on Aadhaar starts to make a little sense. For a while now, the authority has wished to undertake mass digital surveillance through social media and other online forums in order to track “top detractors” of the Aadhaar scheme and counter them to effectively “neutralise negative sentiments” surrounding the project.

This move, however, was challenged by petitioner Mahua Moitra who saw it as “an attempt by the State to overreach the jurisdiction of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in matters where the legality of social media surveillance and Aadhaar itself is under challenge”.

For now, the next time we are hit with a sense of déjà vu when it comes to an Aadhaar-related security incident, we should see through the UIDAI’s statements for what they truly are: hopeless attempts at damage control for a system that is crumbling at its very foundation.