Is India Prepared for a Cyber Attack? Suckfly And Other Past Responses Say No

From mandatory disclosures to improving CERT-IN’s functioning and transparency, there is much to be done in the event of future cyber attacks.

The article by Sushil Kambampati was published in the Wire on September 21, 2016. Pranesh Prakash was quoted.

In early September, details about India’s top secret Scorpene submarine program were published online. This presumed data breach brought the issue of cyber security into the headlines.

However, earlier this year, news of potentially catastrophic breaches of Indian networks barely made a blip. On May 17, the cyber-security firm Symantec stated in a blog post that it had traced breaches of several Indian organisations to a cyber-espionage group called Suckfly. The targeted systems belonged to the central government, a large financial institution, a vendor to the largest stock exchange and an e-commerce company. The espionage activity began in April 2014 and continued through 2015, Symantec said. Based on the targets that were penetrated, Symantec speculated that the espionage was targeted at the economic infrastructure of India. Such allegations should be ringing alarm bells inside the government and amongst private businesses across the country. And yet, from the official public response, one would think nothing was amiss.

A week later, another cyber-security firm, Kaspersky Lab, announced that it too had tracked at least one cyberespionage group, called Danti, that had penetrated Indian government systems through India’s diplomatic entities.

Breaches of corporate and government networks are nothing new. Usually, these breaches come to light if the perpetrators reveal the attack, the target of the attack discloses the breach, or because the leaked data shows up on the Internet. The Suckfly and Danti breaches are unusual because they were reported by a third party while the targets (in this case, Indian organisations and the government) themselves have remained silent. The breaches reported by Symantec and Kaspersky of Indian organisations received tepid coverage in India. A few news organisations published the same wire story that basically rewrote information in the original posts, but there was very little follow-up as there was not much follow-up investigation to determine the targets or an analysis to gauge how much damage the leaks could cause.

Part of the reason there was no fallout may have to do with the reluctance of the parties involved to provide information. Symantec, in response to multiple requests for more details, kept referring to the original blog post. The government made no statement either confirming or denying the report. Several banks, e-commerce companies and government agencies were asked whether they were aware of Suckfly, whether they had been breached by the organisation and whether Symantec had contacted them. Only Yatra, Axis Bank and Flipkart responded, denying that they had been penetrated by Suckfly. The National Stock Exchange also said it had not been penetrated, although the questions asked were about whether any of the stock exchange’s vendors had been penetrated and if they had been, whether the NSE knew about such a breach.

This collective lack of response across the board indicates a mindset that shows unpreparedness for the cyber threats that are very real, existent and ongoing. Compare the Suckfly reaction to the threat of a terrorist infiltration. In that scenario, the government goes on high alert, resources are mobilised and the public is warned. The government then tries to identify the threat and stop it from doing any harm. Citizens demand that in the future the government take proactive steps to catch infiltrators and prevent any future threats.

Weak government response

One method that Suckfly uses to gain access, according to Symantec, is by signing its malware with stolen digital certificates. This is the same method that was used to infect and sabotage the Iranian nuclear centrifuges with the Stuxnet virus, so the potential for harm of these breaches cannot be understated. Several security experts confirmed the plausibility of such doomsday scenarios as two-factor authentication being turned off for credit card transactions, unauthorised money transfers, leakage of credit card details, stolen password hashes or personal information, massive numbers of fake e-commerce orders and the manipulation of the stock exchange.

All the targets taken together, the potential for economic damage that the Suckfly breach poses is immense. If another country or malevolent group wanted to wreak havoc in India, it could trigger banking panic by emptying accounts or a stock-market collapse by dumping stocks at fractional values.

Even more disturbing, though, is that if a foreign entity has access to government networks, it has the potential to collect passwords to critical systems using key-loggers and password scanners. From there the entity could steal national security data, disrupt control systems of electrical grids or nuclear facilities and gain access to everything the government knows about its citizens, including personal details, financial information and identity information. On an only slightly less dangerous level, the central bank’s funds could be stolen, like the recent attempt to heist $800 million from the central bank of Bangladesh.

A report on risks facing India, published in August by KPMG and the Confederation of Indian Industry said: “While traditionally cyber attacks were largely used for causing financial and reputational loss, today they have a potential of posing a threat to human life. While the perpetrators behind these attacks traditionally were a few challenge loving ‘hackers’ with unbridled curiosity, we see an increasing number of state sponsored cyber terrorists and organised criminals behind the attacks today.”

In light of such serious threats, the government needs to take more action to mitigate the threat and reassure the public that it is on top of the situation. Reports of encounters between the armed forces and alleged terrorists are frequently relayed to the press. Similarly, the National Informatics Centre (NIC) or its parent organisation, the Department of Electronics and Information Technology, needs to make a public statement when breaches of government systems or of private organisations at this scale come to light. The investigative agencies need to open an enquiry into the matter.

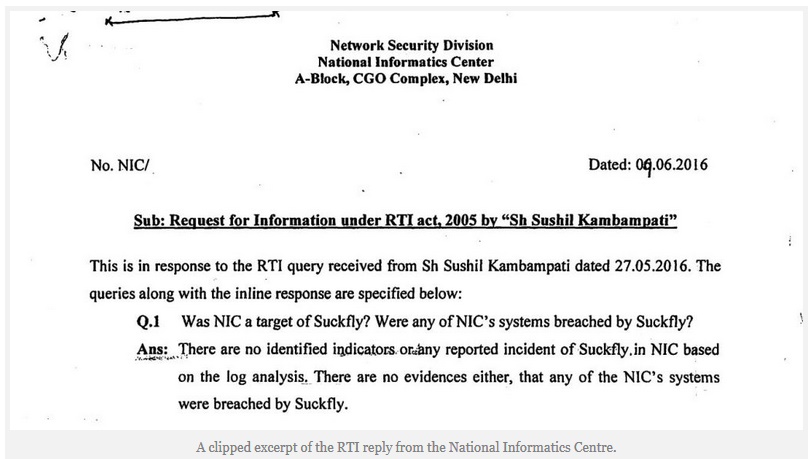

In the Suckfly case, it took a right-to-information query from this author to get a response from the NIC. In the response, the NIC stated that it was unaware of any breach of its systems by Suckfly, that it did not use Symantec’s services and that Symantec had not notified NIC of any breach. Of course, the response also raises many more questions, which could be asked if the government took an attitude of openness and disclosure.

The government also needs to step up its efforts of identifying and neutralising the threat. The Indian government’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-IN) is responsible, according to its website, for “responding to computer security incidents as and when they occur” and also collecting information on and issuing “guidelines, advisories, vulnerability notes and whitepapers relating to information security practices, procedures, prevention, response and reporting of cyber incidents.” Yet, as of September 12, its website does not mention the Backdoor.Nidoran exploit which Suckfly allegedly used to gain access during at least one of its attacks. The CVE-2015-2545 vulnerability that Danti used, according to Kaspersky, is also unlisted. Any organisation or person relying on CERT-IN to get notifications of vulnerabilities would be in the dark and exposed to a breach.

CERT-IN is a perfect example of where the government could really do so much more, starting with some very basic things. For example, by design, contact e-mail addresses listed on the site cannot be clicked on or copied, and so have to be retyped. Such a measure would barely stop even a novice hacker. E-mail messages sent to one of the contact email address bounce back. While it laudably posts its e-mail encryption hash on its contact page, one of the identifiers does not match what is registered in the public KeyStores (usually that would be a sign of a hack). Most glaringly, anyone searching for information on a vulnerability on the site will have to click in and out of every document because the site does not have a search function. Collectively, these flaws give the impression that while the government has thought about cyber-security, it is not putting enough resources and effort into making that a credible initiative.

The government’s regulatory agencies also need to get into the fray. For example, one of the organisations that Suckfly allegedly breached is a large financial institution. It makes sense, therefore that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which oversees all financial institutions, should make it mandatory that a bank notify the RBI whenever there is a security breach. The RBI did just that in a notification issued on June 2, 2016, after the Suckfly breach. However, the notification does not address the need to inform the public. The RBI itself also needs to be more forthcoming. In the Suckfly instance the RBI has not made any statements about whether financial institutions under its supervision are secure. It took an RTI query to get a statement from the RBI, and there it responded that it had no information on the matter.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), which oversees the country’s stock exchanges, initially did not respond directly as to whether it knew of the breach at any IT firm that supplies an Indian stock exchange. However, SEBI reacted to an RTI query by asking all the stock exchanges under its mantle to verify with each of their IT vendors whether there had been any breach. They all denied it. If any of them are being untruthful, they have made a false statement to SEBI. However, if taken at their word, the public can take comfort in the fact that the stock market was not compromised by this attack.

SEBI also issued a cyber-security policy framework for its stock exchanges in July 2015, around the time when Suckfly may have been actively attacking systems. Where the RBI asks financial institutions to report breaches within six hours of detection, SEBI requires the reports to be quarterly. Given how fast information travels and how many transactions can be done in mere minutes, that seems like too much time for SEBI to take any effective action. SEBI’s policy also does not address the need to inform the public.

What is needed is a coordinated, comprehensive and unified policy that applies to stock exchanges, financial institutions, government organisations and private companies. It doesn’t matter from where the data is being stolen, what matters is how quickly the organisation learns of it and lets people know so that they too can take any action they need to.

Right or wrong?

The across-the-board denials of any breach raise the question whether Symantec was mistaken. Skeptics could even wonder whether the company exaggerated the situation to increase sales of its products and services. For its part, Symantec refuses to provide any further information about the breach beyond what is in its initial post; crucial information in this regard would include more forensic details, which could identify whether the breach actually took place. Symantec also would not confirm whether it had notified the targets of the attacks, though the government says it has not been alerted by Symantec.

On the other hand, according to Sastry Tumuluri, a former Chief Information Security Officer for the state of Haryana, Symantec probably did correctly identify the breaches. Symantec collects vast amounts of information at every point where it has a presence, such as on individual computers, at internet interconnection points and web hosts globally. All that data can give a fairly accurate and reliable indication of systems being penetrated. Depending on their capabilities and level of sophistication, the target organisations could also truthfully say that they have not detected a breach.

If Symantec’s is correct in conjecturing that the Suckfly breach targeted India’s economic sector, its lack of further action is disturbing. India is one of the world’s ten largest economies and instability here would have ripple effects globally. Then there is the potential of catastrophic cyberterrorism. It is in everyone’s interest that Symantec reach out to the government and to let the public know which organisations may be compromised.

According to Pranesh Prakash, Policy Director at the Centre for Internet and Society and Bruce Schneier, a globally recognised security expert, the lack of knowledge regarding which organisations were targeted reduces people’s trust in the Internet across the board. In an email response, Schneier wrote, “Symantec has an obligation to disclose the identities of those attacked. By leaving this information out, Symantec is harming us all. We all have to make decisions on the Internet all the time about who to trust and who to rely on. The more information we have, the better we can make those decisions.”

Looking at it in the other direction, it is not apparent whether the government has asked Symantec and Kaspersky for more information and a disclosure of who the targets were. After all, if government systems were breached, it is a matter of national security. If the government has indeed reached out and received more information, it has an obligation to let the public know.

What other governments and private companies are belatedly learning is that it is better to proactively disclose the breaches before the information gets out through other parties. When US retailer Target came under attack, its data breach was first revealed by security reporter Michael Krebs. Target was criticised for not coming forth itself and faced several lawsuits. In the US, most states and jurisdictions have laws that require companies to disclose data breaches, although transparency advocates point out that there is great variation on how long companies can wait to disclose and what events trigger a mandatory disclosure. In Europe, telecoms and Internet Service Providers must report a breach within 24 hours and other organisations have 72 hours.

India has no mandatory disclosure law in the case of data breaches at government or private organisations, Prakash said. It is something that CIS supports and had proposed since 2011, he added.

According to Schneier, a mandatory disclosure law would also be valuable if confidentiality agreements would otherwise prevent a security firm such as Symantec from disclosing names of targets.

Finally, private companies need to understand that they are not doing themselves any favours by remaining silent on the matter. Even if Suckfly or its clients do not use the information they may have gained, the lack of disclosure by the targets will weaken trust in online commerce and financial transactions, says Prakash. For example, looking at e-commerce, while it is true that e-commerce has grown rapidly in India, a study in 2014 by YourStory and Kalaari Capital found that lack of trust and doubt about online security were hurdles for 80% of people who had never made an online purchase.

When an organisation lets the public know that it has been breached, users of the service or site can evaluate what action they need to take. For example if a person uses the same password across multiple sites, they would know they needed to change the password at the other sites. Depending on the breach they would also be able to alert credit card companies as well as friends and family.

As the KPMG report states, cyber attacks are only going to become more common. Despite multiple warnings, the response on the part of the Indian government and private organisations has been quite underwhelming. The government needs to proactively monitor and respond to attacks. Lawmakers need to pass laws establishing privacy policies and mandatory disclosures. Companies will also need to invest in better security practices as well as gain public trust by reacting to breaches promptly and letting the public know what they are doing to recover from them.