How To Win Friends, FB Style

True to form—and Facebook—there was a warm, friendly and familial feel to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s townhall meeting at Melon, California, with Mark Zuckerberg on September 27. Modi got emotional (yet again) while talking about his mother. Zuckerberg, the youngish founder of the world’s largest social networking site, got his parents to meet and pose with Modi.

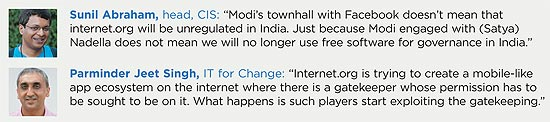

The article by Arindam Mukherjee was published in Outlook on October 12, 2015. Sunil Abraham was quoted.

“The most amazing moment was when I talked about our families,” Zuckerberg wrote in a post, “and he (Modi) shared stories of his childhood....” That’s just the kind of stuff we would see and post on Facebook—the benign visage of a profitable, all-pervasive US-based corporation. (Needless to say, everyone who has worked on this story is a registered user).

Of course, we know Modi too is on Facebook. No other Indian politician has so effectively utilised the power of ‘likes’: and he has got 30 million. The problem with this chummy approach is that one could almost forget that the PM is also the supreme leader of a country that is Facebook’s second-largest market in the world with 125 million users. A few days earlier, Zuckerberg flew to Seattle to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping. Facebook is not present in China. “On a personal note, this was the first time I’ve ever spoken with a world leader entirely in a foreign language,” wrote Zuckerberg in another post.

In contrast, Modi and Zuckerberg were speaking the same language. In fact, they even jointly updated their profile picture on Facebook—wrapped in the shades of the Indian tricolour—to support the Modi government’s Digital India initiative. Millions of Indians followed suit. And that’s when the shit hit the internet—it was discovered that people supporting the Digital India campaign were also putting in a ‘yes’ vote for Facebook’s contentious initiative internet.org (free but restricted net access; see accompanying faqs for all the details). Immediately, Modi became a party to the raging debate in India over net neutrality. This is unfortunate as the Modi government is yet to put on paper its stand on net neutrality. The nervous reaction to this engagement is also a function of the new truism of our times—“with this government, you never know”.

What we do know is that the internet.org class name was built into the code for support for Digital India. Many experts feel this is not a coincidence; rather a clever ploy by Facebook to get the support of Indians and promote its internet.org initiative. This upset a vocal community of activists who see internet.org on the opposite camp. This led to the charge that Facebook was trying to influence the debate. Says Sunil Abraham, executive director with the Bangalore-based Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), “The moves by Facebook are quite juvenile as it is trying to use the Modi visit to further muddy the net neutrality debate. We should be concerned about Facebook trying to damage the debate in India to spin the PM’s participation in its own favour.” Of course, there are two sides to this debate. There are many people within the government who feel net neutrality is an elitist concern—increasing internet penetration, which Facebook and other such initiatives promise, is the way forward in a poor, unconnected country like India. “Today to talk about net neutrality is to talk about the 20 per cent who have access to the internet,” says telecom expert Mahesh Uppal. “It is unreasonable to dismiss out of hand anybody who offers free service to a subset of websites or services. Eventually, access to internet must come first before we talk about net neutrality.”

Facebook promoted internet.org along with Samsung, Nokia, Qualcomm, Ericsson, MediaTek and Opera Software, the aim being to provide free internet service to developing nations. India, obviously, is a hot target for Facebook. Facebook has a partnership with Reliance in the country; the free internet service will be available only to Reliance users and the free access will be limited to Facebook’s partner sites. The debate over internet.org too has picked up steam in India—big media companies like NDTV and Times of India have pulled out of it on these issues. While Facebook has stressed that internet.org will ensure that the internet reaches people who do not have access to it, there have been concerns that it will restrict internet access only to sites that are internet.org’s partners.

On its part, Facebook has been quick to refute the charge. A spokesperson in the US said, “There is absolutely no connection between updating your profile picture for Digital India and internet.org. An engineer mistakenly used the words ‘internet.org profile picture’ as a shorthand name he chose for part of the code.” The code was changed soon after. Despite repeated requests, representatives from Facebook India were unavailable for comment.

But the damage has been done. Many now openly question Facebook’s motives in India and whether they have been truthful or not. Given all this brouhaha, questions will naturally be raised about Modi’s alignment with Facebook. Digital India is many things—but obviously increasing net penetration is one its goals. “Now whatever he does on net neutrality, it will be seen in terms of whether it will benefit Google or Facebook. That is the risk he took. I would like to know why the diplomatic advisors took the risk of putting the PM in a bargaining position instead of a bonus at the end of a deal,” says Prof Narendar Pani, who teaches at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore.

All this matters because the Modi government positions itself as digital-friendly, even though its moves on this front have been invasive (the push for Aadhar despite a legal sanction and increasing reports of monitoring digital conversations), and contradictory (the abortive porn and WhatsApp bans, among others). “The PM is going way beyond the e-governance plan to a stage where the government will just sit and watch people speaking. It is scary,” says internet activist Usha Ramanathan. She feels it doesn’t make sense to have companies like Google sharing ideas with the government while Indian people are being kept out of the loop. “And now Facebook will be joining that gang, it doesn’t make sense. What has Facebook done to get that privilege?” she asks.

Here again there is a carefully worded counter-argument. Former telecom entrepreneur and Rajya Sabha MP Rajeev Chandrashekhar says, “Net neutrality is a definition that would be made in the public domain. It will not be influenced by the PM’s engagement with Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg. Anyone who tries to mess with the definition of net neutrality will be met with a public outcry and judicial intervention.” The substance of this view is that Modi was within his rights to speak to corporations to further Digital India, or Make in India for that matter, and that there should be an open debate on the future direction of net neutrality.

Clearly, the political knives are out. “Either the prime minister is not being briefed properly or he does not read his brief properly,” says former UPA minister Manish Tewari. Arguing that governments should be discussing rules of engagement in cyberspace, and not stakeholders, he asks, “Is India comfortable with that construct especially when the bulk of the technology companies, the root servers which form the underlying hardware of the internet, are all based in the US, and one being in Europe?”

Although the government is yet to firm up its decision on net neutrality and a policy on it is yet to be announced, the debate has already acquired political colour in India, with the Congress and Aam Aadmi Party putting their weight behind the people’s voice. This is the first time that there has been a nation-wide upsurge of such an unprecedented size and magnitude on an internet policy. Says AAP’s Adarsh Shastri, “Facebook, Google etc are just tools. People can use them at will. To make them the mainstay of your programme for digital empowerment is to step on the civil rights and liberties of citizens. Doing this is a complete no-no. Let people access internet as they want is the way to go.”

A consultation paper floated by telecom regulator Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) got almost 15 lakh responses from the Indian public in support of net neutrality. There was also strong opposition to zero rating platforms announced by telecom companies like Airtel which sought to provide free access to some websites on their platform in much the same way that internet.org proposes. And the reactions to the Facebook coding error are a pointer to what people in India think. Says Nikhil Pahwa, editor of Medianama and a leading net neutrality activist, “The reactions of the people to the Facebook event were heartening and showed that people are emotive and there is still mass support for net neutrality. The reaction to the TRAI paper was not a flash in the pan.”

Interestingly, a couple of months ago, a department of telecommunications committee had said that internet.org was a violation of net neutrality and should not be allowed. It will be difficult for Modi and the government to overrule that and give it full and free access in India. Internet experts feel that the engagement with India and Modi was a desperate move by Facebook to get numbers from India. Says internet expert Mahesh Murthy, “Facebook is pulling out all stops to get favour for internet.org and is desperate about it. If India says yes, many others will say yes, but if India says no, other countries will follow.”

Murthy says Facebook’s real problem is that it is finding it difficult to justify its price to earnings ratio as against its user numbers vis-a-vis Google which is much better in this respect. For this, it is desperately trying to get numbers, and with China banning Facebook, the only country left to get numbers is India. The massive electronic and print campaign at the cost of Rs 40-50 crore is a pointer towards this. He says everything about internet.org is about hooking Indians to it.

No wonder, Facebook has been cultivating Indian media. The Modi visit has also been tarnished by the news that Facebook paid for the travel and accommodation of journalists from three Indian newspapers and one magazine to go and cover the Facebook-Modi meeting and get favourable coverage. Says writer-activist Arundhati Roy, “Many journalists covering the event for the Indian media were flown in from India by Facebook. So were some who asked pre-assigned questions at the event. I don’t know who sponsored the crocodile tears and the clothes.” It is also quite strange that the entire display picture and source code controversy got almost no play in the national media which chose instead to talk about Modi’s speech and his tears.

All said and done, it is obvious that Facebook may be seeing India as an easy and vulnerable target which can be manipulated for its own advantage. Says Parminder Jeet Singh, executive director with IT for Change, an NGO working on information society, “India has low internet penetration and lots of people want to get on to the internet. There is low purchasing power but lots of aspiration. So the moment a free service is offered, a whole lot of people are likely to jump on it.” And that is something Facebook may be looking and aiming at.

Currently, three processes are on that will determine how India will look at net neutrality—one at the DoT, one at TRAI and a third one at a parliamentary standing committee. But given the massive people’s response net neutrality has got vis-a-vis TRAI’s paper and also during the present Facebook issue, the outcome is predictable. Or so it seems. There’s a lot of money power at stake. For now, millions of internet Indians have already voted with that dislike button. And then, governments move in mysterious ways.