India's Aadhaar with biometric details of its billion citizens is making experts uncomfortable

"Indians in general have yet to understand the meaning and essence of privacy," says Member of Parliament, Tathagata Satpathy.

The blog post was published by Mashable India on February 14, 2017. Sunil Abraham was quoted.

But on Feb. 3, privacy was the hot topic of debate among many in India, thanks to a tweet that showed random people being identified on the street via Aadhaar, India's ubiquitous database that has biometric information of more than a billion Indians.

That's how India Stack, the infrastructure built by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), welcomed OnGrid, a privately owned company that is going to tap on the world's largest biometrics system, conjuring images of Minority Report style surveillance.

But how did India get here?

Aadhaar's foundation

Not long ago, there were more people in India without a birth or school certificate than those with one (PDF). They had no means to prove their identity. This also contributed to what is more popularly known as “leakage” in the government subsidy fundings. The funds weren’t reaching the right people, in some instances, and much of it was being siphoned off by middlemen.

Nearly a decade ago, the government began scrambling for ways to tackle these issues. Could technology come to the rescue? The government dialled techies, people like Nandan Nilekani, a founder of India's mammoth IT firm Infosys, for help.

In 2008, they formulated Aadhaar, an audacious project "destined" to change the prospects of Indians. It was similar to Social Security number that US residents are assigned, but its implications were further reaching.

At the time, the government said it will primarily use this optional program to help the poor who are in need of services such as grocery and other household items at subsidized rates.

Eight years later, Aadhar, which stores identity information such as a photo, name, address, fingerprints and iris scans of its citizens and also assigns them with a unique 12-digit number, has become the world's largest biometrics based identity system.

According to the Indian government, over 1.11 billion people of the country's roughly 1.3 billion citizens have enrolled themselves in the biometrics system. About 99 percent of all adults in India have an Aadhaar card, it said last month.

Today, the significance of Aadhaar, which on paper remains an optional program, is undeniable in the country. The government says Aadhaar has already saved it as much as $5 billion.

But that's not it.

There's a bit of Aadhaar in everyone's life

Aadhaar (Hindi for foundation) has long moved beyond helping the poor. The UPI (Unified Payment Interface), another project by the Indian government that uses Aadhaar, is helping the country's much unbanked population to avail financial services for the first time. Nilekani calls it a "WhatsApp moment" in the Indian financial sector.

In December last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched BHIM, a UPI-based payments app that aims to get millions of Indians to do online money transactions for the first time, irrespective of which bank they had their accounts with. With BHIM, transferring money is as simple as sending a text message. People can also scan QR codes and pay merchants for their purchases.

"This app is destined to replace all cash transactions," Modi said at the launch event. "BHIM app will revolutionize India and force people worldwide to take notice," he added.

The next phase, called Aadhaar Enabled Payments System will do away with smartphones. People will be able to make payments by swiping their finger on special terminals equipped with fingerprint sensors rather than swiping cards.

Last year, the government said people could store their driver license documents in an app called DigiLocker, should they want to be relieved from the burden of carrying paper documents. DigiLocker is a digital cloud service that any citizen in India can avail using their Aadhaar information.

The government also plans to hand out "health cards" to senior citizens, mapped to their Aadhaar number, which will store their medical records, which doctors will be able to access.

“Aadhaar is an instrument for good governance. Aadhaar is the mode to reach the poor without the middlemen,” Ravi Shankar Prasad, India’s IT minister said in a press conference last year.

But despite all the ways Aadhaar is making meaningful impact in millions of lives, some people are very skeptical about it. And for them, the scale at which Aadhaar operates now is only making things worse.

A security nightmare

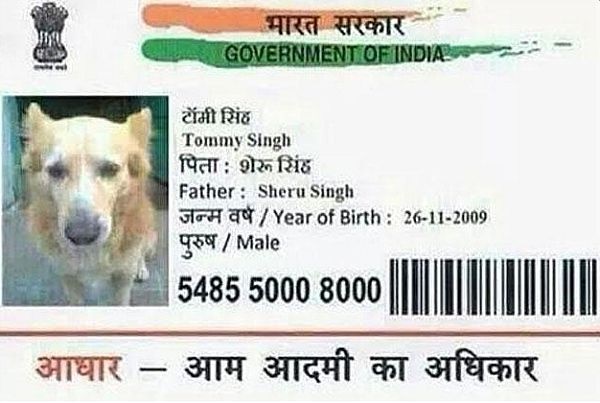

There have been multiple reports suggesting bogus and fake entries in Aadhaar database. Instances of animals such as dogs and cows having their own Aadhaar identification numbers have been widely reported. In one instance, even Hindu god Hanuman was found to have an Aadhaar card.

The problem, it appears, is Aadhaar database has never been verified or audited, according to multiple security experts, privacy advocates, lawyers, and politicians who spoke to Mashable India this month.

“There are two fundamental flaws in Aadhaar: it is poorly designed, and it is being poorly verified,” Member of Parliament and privacy advocate, Rajeev Chandrasekhar told Mashable India. “Aadhaar isn’t foolproof, and this has resulted in fake data get into the system. This in turn opens new gateways for money launderers,” he added.

Another issue with Aadhaar is, Chandrasekhar explains, there is no firm legislation to safeguard the privacy and rights of the billion people who have enrolled into the system. There’s little a person whose Aadhaar data has been compromised could do. “Citizens who have voluntarily given their data to Aadhaar authority, as of result of this, are at risk,” he added.

Rahul Narayan, a lawyer who is counselling several petitioners challenging the Aadhaar project, echoed similar sentiments. “There’s no concrete regulation in place,” he told Mashable India. “The scope for abuses in Aadhaar is very vast,” he added.

But regulation — or its lack thereof — is only one of the many challenges, experts say. Sunil Abraham, the executive director of Bangalore-based research organisation the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), says the security concerns around Aadhaar are alarming.

“Aadhaar is remote, covert, and non-consensual,” he told Mashable India, adding the existence of a central database of any kind, but especially in the context of the Aadhaar, and at the scale it is working is appalling.

Abraham said fingerprint and iris data of a person can be stolen with little effort — a “gummy bear” which sells for a few cents, can store one’s fingerprint, while a high resolution camera can capture one’s iris data.

Aadhaar doesn’t use basic principles of cryptography, and much of its security is not known.

Aadhaar is also irrevocable, which strands a person, whose data has been compromised, with no choice but to get on with life, Abraham said, adding that these vulnerabilities could have been averted had the government chosen smart cards instead of biometrics.

On top of this, he added, that Aadhaar doesn’t use basic principles of cryptography, and much of the security defences it uses are not known.

Had the government open sourced Aadhaar code to the public (a common practice in the tech community), security analysts could have evaluated the strengths of Aadhaar. But this too isn’t happening.

At CIS, Sunil and his colleagues have written over half-a-dozen open letters to the UIDAI (the authority that governs Aadhaar project) raising questions and pointing holes in the system. But much of their feedback has not returned any response, Abraham told Mashable India.

India Stack: A goldmine for everyone

As part of its push to make Aadhaar more useful, the UIDAI created what is called India Stack, an infrastructure through which government bodies as well as private entities could leverage Aadhaar's database of individual identities. This is what sparked the initial debate about privacy when India Stack tweeted the controversial photo.

Speaking to Mashable India, Piyush Peshwani, a founder of OnGrid, however dismissed the concerns, clarifying that the picture was for representation purposes only. He said OnGrid is building a trust platform, through which it aims to make it easier for recruiters to do background check on their potential employees after getting their consent.

India Stack and OnGrid have since taken down the picture from their Twitter accounts. "OnGrid, much like other 200 companies working with UIDAI, can only retrieve information of users after receiving their prior consent," he said.

The lack of information from the UIDAI and India Stack is becoming a real challenge for citizens, many feel. There also appears to be a conflict of interest between the privately held companies and those who helped design the framework of Aadhaar.

As Rohin Dharmakumar, a Bangalore-based journalist pointed out, Peshwani was part of the core team member of Aadhaar project. A lawyer, who requested to be not identified, told Mashable India that there is a chance that these people could be familiar with Aadhaar’s roadmap and use the information for business advantage, to say the least.

Most people Mashable India spoke to are questioning the way these third-party companies are handling Aadhaar data. There is no regulation in place to prevent these companies from storing people’s data or even creating a parallel database of their own — a view echoed by Abraham, Narayan, and Chandrasekhar.

Not mandatory only on paper

But for many, the biggest concern with Aadhaar remains just how aggressively it is being implemented into various systems. For instance, in the past one month alone, students in most Indians states who want to apply for NEET, a national level medical entrance test, were told by the education board CBSE that they will have to provide their Aadhaar number.

A few months ago, Aadhaar was also made mandatory for students who wanted to appear in JEE, an all India common engineering entrance examination conducted for admission to various engineering colleges in the country.

The apex Supreme Court of India recently asked the central government to register the phone number of all mobile subscribers in India (there are about one billion of those in India) to their respective Aadhaar cards. Telecom carriers are already enabling new connections to get activated by verifying users with Aadhaar database.

A prominent journalist who focuses on privacy and laws in India questioned the motive. “When they kickstarted UIDAI, people were told that this an optional biometrics system. But since then the government has been rather tight-lipped on why it is aggressively pushing Aadhaar into so many areas,” he told Mashable India, requesting not to be identified.

"It is especially difficult to explain why privacy is necessary for a society to advance when taken in the context of Aadhaar."

“It is especially difficult to explain why privacy is necessary for a society to advance when taken in the context of Aadhaar. The Aadhaar card is being offered to people in need, especially the poor, by making them believe that services and subsidies provided by the government will be held back from them unless they register,” Satpathy told Mashable India.

The central government said last week Aadhaar number would be mandatory for availing food grains through the Public Distribution System under the National Food Security Act. In October last year, the government made Aadhaar mandatory for those who wanted to avail cooking gas at subsidized prices.

“No matter how many laws are made about not making Aadhaar mandatory, ultimately it depends on the last mile person who is offering any service to inform citizens about their rights,” Satpathy added.

“These last-mile service providers are companies who would benefit from collecting and bartering big data for profit. They would be least interested to inform citizens about their rights and about the not mandatory status of Aadhaar.

“As Aadhaar percolates more and is used by more government and private services, the citizen will start assuming it's a part of their life. This card is already being misunderstood as if it is essential like a passport,” he added.

“My worry is that this data will be used by government for mass surveillance, ethnic cleansing and other insidious purposes,” Satpathy said. “Once you have information about every citizen, the powerful will not refrain from misusing it and for retention of power. The use of big data for psycho-profiling is not unknown to the world anymore.”

Mashable India reached out to UIDAI on Feb. 8 for comment on the privacy and security concerns made in this report. At the time of publication, the authority hadn't responded to our queries.