Lack of clarity about cashless and online transactions makes digital payments more worrisome

Even as demonetisation pushes for more and more cashless and online transactions through, e-wallets, banks and other such apps, there is a serious lack of clarity on how these companies handle customer data, and how it is shared with other entities. "Data is the new oil," is an oft repeated phrase in nearly every technology related conversation that comes up anywhere in India today.

The article by Neha Alawadhi was published in the Economic Times on December 1, 2016. Sunil Abraham was quoted.

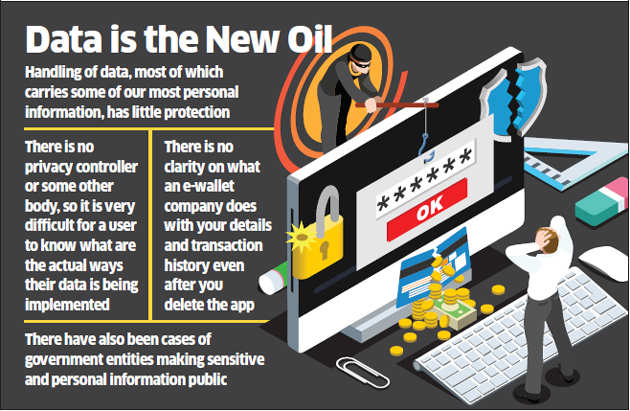

However, the handling of this data, most of which carries some of our most personal information, has little protection if it is misused by a private or government entity.

Sample this: at an industry event, a Bengaluru-based startup claimed to solve the problem of credit worthiness of individuals for small loans by using some unusual means. To determine credit worthiness, the company maps everything in your phone — right from how many SMSes you receive for non-payment of dues, to how you fill out your loan application form. The company also claims that it can map, using your phone data, the area of your residence and office.

There are several other companies, especially those in the financial technology (fintech) space, doing similar mapping. The Wall Street Journal on Monday reported that more than three dozen local governments across China are compiling digital records of social and financial behaviour to rate credit worthiness. A person gets a score deduction for violations such as fare cheating, jaywalking and violating family-planning rules.

India may be some distance away from such a credit scoring system, but the increased use of online transactions — financial or otherwise — is sure to lead to similar business models.

"You have no clue what data you are sharing with fintech companies. They are collecting data from other sources and combining it to assess your credit score," said Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Centre for Internet Society.

For example, there is no clarity on what an e-wallet company does with your details and transaction history even after you delete the app. "If there is large level of customer migration of users from an app company, they will just become a data analytics company. The bigger danger in future is the growth of large data intermediaries which are similar to Visa and Mastercard networks, which purchase big databases and further sell this data and build their services or product on top of that. There are large privacy concerns there," said Apar Gupta, advocate and Internet policy expert. While lack of a privacy law or controller has been a long standing concern, the existing law for data protection — Section 43(A) of the Information Technology Act— also offers only very basic protection and is "grossly inadequate", according to Abraham.

To make matters worse, they also lack a strict enforcement mechanism. "We don’t know what are the data practices (adopted by apps). There is no privacy controller or some other body, so it is very difficult for a user to know what are the actual ways their data is being implemented," said Gupta.

There have also been cases of government entities making sensitive and personal information public. Earlier this year, DataMeet, a community of data science enthusiasts, found that Bengaluru Police released 13,000 call data records (CDR) of potential on-going investigations during a hackathon with focus on solving problems of cities.

"There has been very little talk about data ethics and data practices in India. But cases of misuse of data are frequent," noted DataMeet member Srinivas Kodali in a blogpost.