Navigating the 'Reconsideration' Quagmire (A Personal Journey of Acute Confusion)

An earlier analysis of ICANN’s Documentary Information Disclosure Policy already brought to light our concerns about the lack of transparency in ICANN’s internal mechanisms. Carrying my research forward, I sought to arrive at an understanding of the mechanisms used to appeal a denial of DIDP requests. In this post, I aim to provide a brief account of my experiences with the Reconsideration Request process that ICANN provides for as a tool for appeal.

Backdrop: What is the Reconsideration Request Process?

The Reconsideration Request process has been laid down in Article IV, Section 2 of the

ICANN Bylaws. Some of the key aspects of this provision have been outlined below[1],

- ICANN is obligated to institute a process by which a person materially affected by ICANN action/inaction can request review or reconsideration.

- To file this request, one must have been adversely affected by actions of the staff or the board that contradict ICANN’s policies, or actions of the Board taken up without the Board considering material information, or actions of the Board taken up by relying on false information.

- A separate Board Governance Committee was created with the specific mandate of reviewing Reconsideration requests, and conducting all the tasks related to the same.

- The Reconsideration Request must be made within 15 days of:

- FOR CHALLENGES TO BOARD ACTION: the date on which information about the challenged Board action is first published in a resolution, unless the posting of the resolution is not accompanied by a rationale, in which case the request must be submitted within 15 days from the initial posting of the rationale;

- FOR CHALLENGES TO STAFF ACTION: the date on which the party submitting the request became aware of, or reasonably should have become aware of, the challenged staff action, and

- FOR CHALLENGES TO BOARD OR STAFF INACTION: the date on which the affected person reasonably concluded, or reasonably should have concluded, that action would not be taken in a timely manner

- .The Board Governance Committee is given the power to summarily dismiss a reconsideration request if:

- the requestor fails to meet the requirements for bringing a Reconsideration Request;

- it is frivolous, querulous or vexatious; or

- the requestor had notice and opportunity to, but did not, participate in the public comment period relating to the contested action, if applicable

- If not summarily dismissed, the Board Governance Committee proceeds to review and reconsider.

- A requester may ask for an opportunity to be heard, and the decision of the Board Governance Committee in this regard is final.

- The basis of the Board Governance Committee’s action is public written record information submitted by the requester, by third parties, and so on.

- The Board Governance Committee is to take a decision on the matter and make a final determination or recommendation to the Board within 30 days of the receipt of the Reconsideration request, unless it is impractical to do so, and it is accountable to the Board to make an explanation of the circumstances that caused the delay.

- The determination is to be made public and posted on the ICANN website.

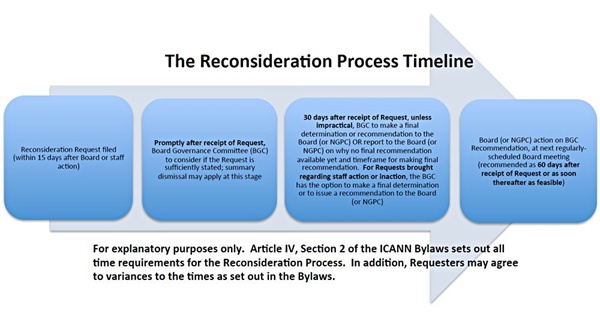

ICANN has provided a neat infographic to explain this process in a simple fashion, and I am reproducing it here:

(Image taken from https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/accountability/reconsiderationen)

Our Tryst with the Reconsideration Process

The Grievance

Our engagement with the Reconsideration process began with the rejection of two of our requests (made on September 1, 2015) under ICANN’s Documentary Information Disclosure Policy. The requests sought information about the registry and registrar compliance audit process that ICANN maintains, and asked for various documents pertaining to the same[2]:

- Copies of the registry/registrar contractual compliance audit reports for all the audits carried out as well as external audit reports from the last year (20142015).

- A generic template of the notice served by ICANN before conducting such an audit.

- A list of the registrars/registries to whom such notices were served in the last year.

- An account of the expenditure incurred by ICANN in carrying out the audit process.

- A list of the registrars/registries that did not respond to the notice within a reasonable period of time.

- Reports of the site visits conducted by ICANN to ascertain compliance.

- Documents which identify the registries/registrars who had committed material discrepancies in the terms of the contract.

- Documents pertaining to the actions taken in the event that there was found to be some form of contractual noncompliance.

- A copy of the registrar selfassessment form which is to be submitted to ICANN.

ICANN integrated both the requests and addressed them via one response on 1 October, 2015 (which can be found here). In their response, ICANN inundated us with already available links on their website explaining the compliance audit process, and the processes ancillary to it, as well as the broad goals of the programme none of which was sought for by us in our request. ICANN then went on to provide us with information on their ThreeYear Audit programme, and gave us access to some of the documents that we had sought, such as the preaudit notification template, list of registries/registrars that received an audit notification, the expenditure incurred to some extent, and so on .

Individual contracted party reports were denied to us on the basis of their grounds for nondisclosure. Further, and more disturbingly, ICANN refused to provide us with the names of the contracted parties who had been found under the audit process to have committed discrepancies. Therefore, a large part of our understanding of the way in which the compliance audit process works remains unfinished.

What we did

Dissatisfied with this response, I went on to file a Reconsideration request (number 1522) as per their standard format on November 2, 2015. (The request filed can be accessed here).As grounds for reconsideration, I stated that “As a part of my research I was tracking the ICANN compliance audit process, and therefore required access to audit reports in cases where discrepancies where formally found in their actions. This is in the public interest and therefore requires to be disclosed...While providing us with an array of detailed links explaining the compliance audit process, the ICANN staff has not been able to satisfy our actual requests with respect to gaining an understanding of how the compliance audits help in regulating actions of the registrars, and how they are effective in preventing breaches and discrepancies.” Therefore, I requested them to make the records in question publicly available “We request ICANN to make the records in question, namely the audit reports for individual contracted parties that reflect discrepancies in contractual compliance, which have been formally recognised as a part of your enforcement process. We further request access to all documents that relate to the expenditure incurred by ICANN in the process, as we believe financial transparency is absolutely integral to the values that ICANN stands by.”

The Board Governance Committee’s response3

The determination of the Board Governance Committee was that our claims did not merit reconsideration, as I was unable to identify any “misapplication of policy or procedure by the ICANN Staff”, and my only issue was with the substance of the DIDP Response itself, and substantial disagreements with a DIDP response are not proper bases for reconsideration

(emphasis supplied).

The response of the Board Governance Committee was educative of the ways in which they determine Reconsideration Requests. Analysing the DIDP process, it held that ICANN was well within its powers to deny information under its defined Conditions for NonDisclosure, and denial of substantive information did not amount to a procedural violation. Therefore, since the staff adhered to established procedure under the DIDP, there was no basis for our grievance, and our request was dismissed..

Furthermore, as a postscript, it is interesting to note that the Board Governance Committee delayed its response time by over a month, by its own admission “In terms of the timing of the BGC’s recommendation, it notes that Section 2.16 of Article IV of the Bylaws provides that the BGC shall make a final determination or recommendation with respect to a reconsideration request within thirty days, unless impractical. To satisfy the thirtyday deadline, the BGC would have to have acted by 2 December 2015. However, due to the timing of the BGC’s meetings in November and December, the first practical opportunity for the BGC to consider Request 1522 was 13 January 2016.”4

Whither do I wander now?

To me, this entire process reflected the absurdity of the Reconsideration request structure as an appeal mechanism under the Documentary Information Disclosure Policy. As our experience indicated, there does not seem to be any way out if there is an issue with the substance of ICANN’s response. ICANN, commendably, is particular about following procedure with respect to the DIDP. However, what is the way forward for a party aggrieved by the flaws in the existing policy? As I had analysed earlier, the grounds for ICANN to not disclose information are vast, and used to deny a large chunk of the information requests that they receive. How is the hapless requester to file a meaningful appeal against the outcome of a bad policy, if the only ground for appeal is noncompliance with the procedure of said bad policy? This is a serious challenge to transparency as there is no other way for a requester to acquire information that ICANN may choose to withold under one of its myriad clauses. It cannot be denied that a good information disclosure law ought to balance the free disclosure of information with the holding back of information that truly needs to be kept private.[3][4] However, it is this writer’s firm opinion that even instances where information is witheld, there has to be a stronger explanation for the same, and moreover, an appeals process that does not take into account substantive issues which might adversely affect the appellant falls short of the desirable levels of transparency. Global standards dictate that grounds for appeal need to be broad, so that all failures to apply the information disclosure law/policy may be remedied.6 Various laws across the world relating to information disclosure often have the following as grounds for appeal: an inability to lodge a request, failure to respond to a request within the set time frame, a refusal to disclose information, in whole or in part, excessive fees and not providing information in the form sought, as well as a catchall clause for other failures.7

Furthermore, independent oversight is the heart of a proper appeal mechanism in such situations[5]; the power to decide the appeal must not rest with those who also have the discretion to disclose the information, as is clearly the case with ICANN, where the Board Governance Committee is constituted and appointed by the ICANN Board itself [one of the bodies against whom a grievance may be raised].

Suggestions

We believe ICANN, in keeping with its global, multistakeholder, accountable spirit, should adopt these standards as well, especially now that the transition looms around the corner. Only then will the standards of open, transparent and accountable governance of the Internet upheld by ICANN itself as the ideal be truly, meaningfully realised. Accordingly, the following standards ought to be met with:

- Establishment of an independent appeals authority for information disclosure cases

- Broader grounds for appeal of DIDP requests

- Inclusion of disagreement with the substantive content of a DIDP response as a ground for appeal.

- Provision of proper reasoning for any justification of the witholding of information that is necessary in the public interest.

[1] Article IV, Section 2, ICANN Bylaws, 2014 available at https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/governance/bylawsen/#IV

[2] Copies of the request can be found here and here.

[3] Katherine Chekouras, Balancing National Security with a Community's RighttoKnow: Maintaining

Public Access to Environmental Information Through EPCRA 's NonPreemption Clause, 34 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev 107, (2007).

[4] Toby Mendel, Freedom of Information: A Comparative Legal Study 151 (2nd edn, 2008).

Id, at 152

34 Available here. https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/reconsideration1522cisfinaldetermination13jan16en.pdf

[5] Mendel, supra note 6.