Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, 419A Rules and IT (Amendment) Act, 2008, 69 Rules

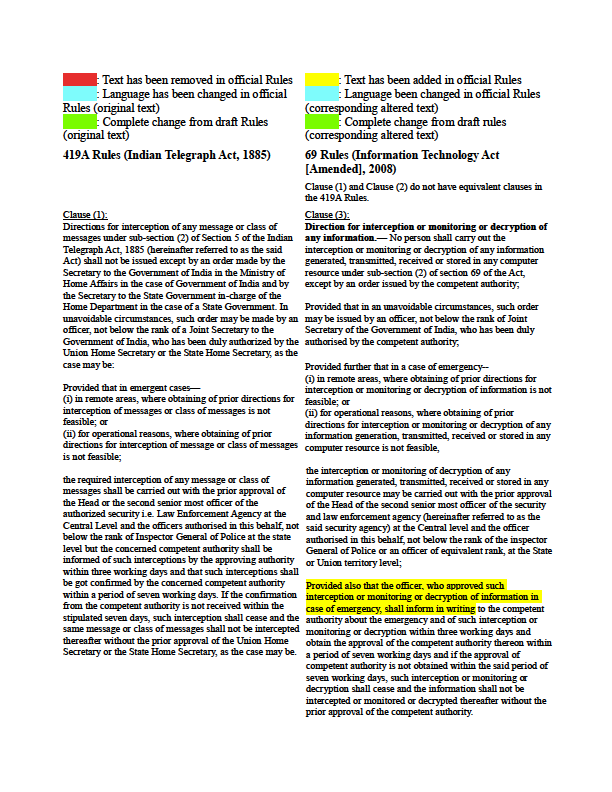

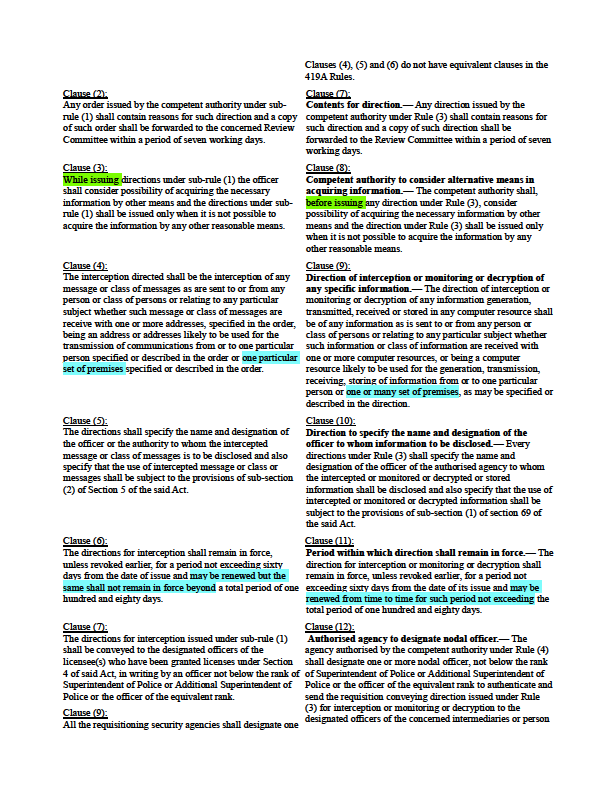

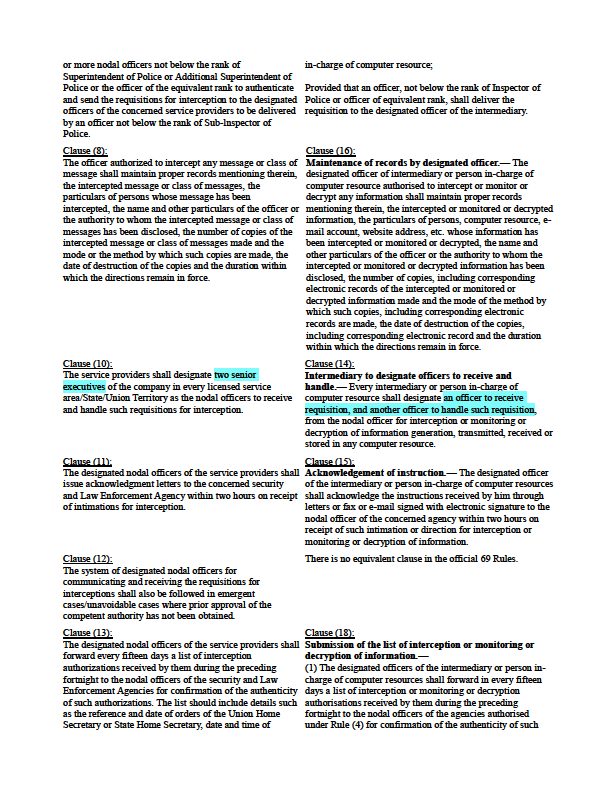

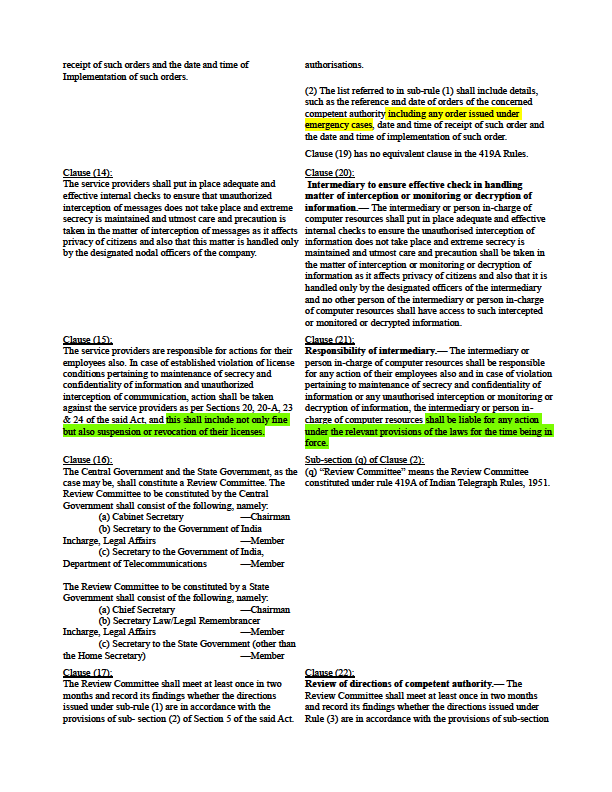

Jadine Lannon has performed a clause-by-clause comparison of the 419A Rules of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 and the 69 Rules under Section 69 of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008 in order to better understand how the two are similar and how they differ. Though they are from different Acts entirely, the Rules are very similar. Notes have been included on some changes we deemed to be important.

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

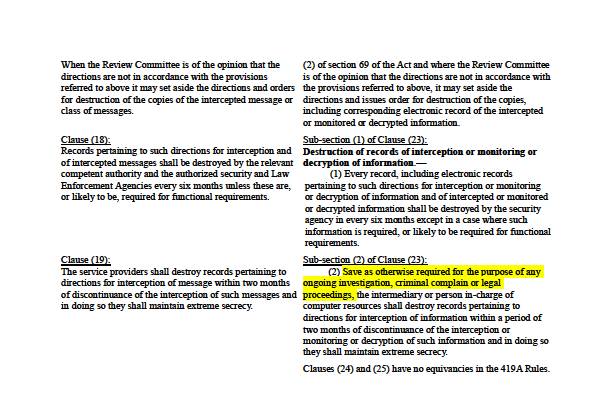

Though they are from different Acts entirely, the 419A Rules from the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 and the 69 Rules from the Information Technology (Amended) Act, 2008 are very similar. In fact, much of the language that appears in the official 69 rules is very close, if not the same in many places, as the language found in the 419A rules. The majority of the change in language between the 419A Rules and the equivalent 69 Rules acts to clarify statements or wordings that may appear vague in the former. Aside from this, it appears that many of the 69 Rules have been cut-and-pasted from the 419A Rules.

Arguably the most important change between the two sets of rules takes place between Clause (3) of the 419A Rules and Clause (8) of the 69 Rules, where the phrase “while issuing directions [...] the officer shall consider possibility of acquiring the necessary information by other means” has been changed to “the competent authority shall, before issuing any direction under Rule (3), consider possibility of acquiring the necessary information by other means”. This is an important distinction, as the latter requires other options to be looked at before issuing the order for any interception or monitoring or decryption of any information, whereas the former could possibly allow the interception of messages while other options to gather the “necessary” information are being considered. It seems unreasonable that the state and various state-approved agencies could possibly be intercepting the personal messages of Indian citizens in order to gather “necessary” information without having first established that interception was a last resort.

Another potentially significant change between the rules can be found between Clause (15) of the 419A Rules, which states, in the context of punishment of a service provider, the action taken shall include “not only fine but also suspension or revocation of their licenses”, whereas Clause (21) of the 69 Rules states that the punishment of an intermediary or person in-charge of computer resources “shall be liable for any action under the relevant provisions of the time being in force”. This is an interesting distinction, possibly made to avoid issues with legal arbitrariness associated with assigning punishments that differ for those punishments for the same activities laid out under the Indian Penal Code. Either way, the punishments for a violation of the maintenance of secrecy and confidentiality as well as unauthorized interception (or monitoring or decryption) could potentially be much harsher under the 69 Rules.

In the same vein, the most significant clarification through a change in language takes place between Clause (10) of the 419A and Clause (14) of the 69 Rules: “the service providers shall designate two senior executives of the company” from the 419A Rules appears as “every intermediary or person in-charge of computer resource shall designate an officer to receive requisition, and another officer to handle such requisition” in the 69 Rules. This may be an actual difference between the two sets of Rules, but either way, it appears to be the most significant change between the equivalent Clauses.

The addition of certain clauses in the 69 Rules can also give us some interesting insights about what was of concern when the 419A rules were being written. To begin, the 419A rules provide no definitions for any of the specific terms used in the Rules, whereas the 69 Rules include a list of definitions in Clause (2). Clause (4) of 69 Rules, which deals which the authorisation of an agency of the Government to perform interception, monitoring and decryption, is sorely lacking in the 419A rules, which alludes to “authorised security [agencies]” without ever providing any framework as to how these agencies become authorised or who should be doing the authorising.

The 69 Rules also include Clause (5), which deals with how a state should go about obtaining authorisation to issue directions for interception, monitoring and/or decryption in territories outside of its jurisdiction, which is never mentioned in 419A rules, lamely sentencing states to carry out the interception of messages only within their own jurisdiction.

Lastly, Clause (24), which deals with the prohibition of interception, monitoring and/or decryption of information without authorisation, and Clause (25), which deals with the prohibition of the disclosure of intercepted, monitored and/or decrypted information, have fortunately been added to the 69 Rules.