FinFisher in India and the Myth of Harmless Metadata

In this article, Maria Xynou argues that metadata is anything but harmless, especially since FinFisher — one of the world's most controversial types of spyware — uses metadata to target individuals.

In light of PRISM, the Central Monitoring System (CMS) and other such surveillance projects in India and around the world, the question of whether the collection of metadata is “harmless” has arisen.[1] In order to examine this question, FinFisher[2] — surveillance spyware — has been chosen as a case study to briefly examine to what extent the collection and surveillance of metadata can potentially violate the right to privacy and other human rights. FinFisher has been selected as a case study not only because its servers have been recently found in India[3] but also because its “remote monitoring solutions” appear to be very pervasive even on the mere grounds of metadata.

FinFisher in India

FinFisher is spyware which has the ability to take control of target computers and capture even encrypted data and communications. The software is designed to evade detection by anti-virus software and has versions which work on mobile phones of all major brands.[4] In many cases, the surveillance suite is installed after the target accepts installation of a fake update to commonly used software.[5] Citizen Lab researchers have found three samples of FinSpy that masquerades as Firefox.[6]

FinFisher is a line of remote intrusion and surveillance software developed by Munich-based Gamma International. FinFisher products are sold exclusively to law enforcement and intelligence agencies by the UK-based Gamma Group.[7] A few months ago, it was reported that command and control servers for FinSpy backdoors, part of Gamma International´s FinFisher “remote monitoring solutions”, were found in a total of 25 countries, including India.[8]

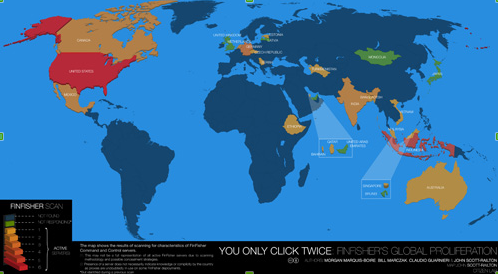

The following map, published by the Citizen Lab, shows the 25 countries in which FinFisher servers have been found.[9]

|

|

|---|

| The above map shows the results of scanning for characteristics of FinFisher command and control servers. |

FinFisher spyware was not found in the countries coloured blue, while the colour green is used for countries not responding. The countries using FinFisher range from shades of orange to shades of red, with the lightest shade of orange ranging to the darkest shade of red on a scale of 1-6, and with 1 representing the least active servers and 6 representing the most active servers in regards to the use of FinFisher. On a scale of 1-6, India is marked a 3 in terms of actively using FinFisher.[10]

Research published by the Citizen Lab reveals that FinSpy servers were recently found in India, which indicates that Indian law enforcement agencies may have bought this spyware from Gamma Group and might be using it to target individuals in India.[11] According to the Citizen Lab, FinSpy servers in India have been detected through the HostGator operator and the first digits of the IP address are: 119.18.xxx.xxx. Releasing complete IP addresses in the past has not proven useful, as the servers are quickly shut down and relocated, which is why only the first two octets of the IP address are revealed.[12]

The Citizen Lab's research reveals that FinFisher “remote monitoring solutions” were found in India, which, according to Gamma Group's brochures, include the following:

- FinSpy: hardware or software which monitors targets that regularly change location, use encrypted and anonymous communications channels and reside in foreign countries. FinSpy can remotely monitor computers and encrypted communications, regardless of where in the world the target is based. FinSpy is capable of bypassing 40 regularly tested antivirus systems, of monitoring the calls, chats, file transfers, videos and contact lists on Skype, of conducting live surveillance through a webcam and microphone, of silently extracting files from a hard disk, and of conducting a live remote forensics on target systems. FinSpy is hidden from the public through anonymous proxies.[13]

- FinSpy Mobile: hardware or software which remotely monitors mobile phones. FinSpy Mobile enables the interception of mobile communications in areas without a network, and offers access to encrypted communications, as well as to data stored on the devices that is not transmitted. Some key features of FinSpy Mobile include the recording of common communications like voice calls, SMS/MMS and emails, the live surveillance through silent calls, the download of files, the country tracing of targets and the full recording of all BlackBerry Messenger communications. FinSpy Mobile is hidden from the public through anonymous proxies.[14]

- FinFly USB: hardware which is inserted into a computer and which can automatically install the configured software with little or no user-interaction and does not require IT-trained agents when being used in operations. The FinFly USB can be used against multiple systems before being returned to the headquarters and its functionality can be concealed by placing regular files like music, video and office documents on the device. As the hardware is a common, non-suspicious USB device, it can also be used to infect a target system even if it is switched off.[15]

- FinFly LAN: software which can deploy a remote monitoring solution on a target system in a local area network (LAN). Some of the major challenges law enforcement faces are mobile targets, as well as targets who do not open any infected files that have been sent via email to their accounts. FinFly LAN is not only able to deploy a remote monitoring solution on a target´s system in local area networks, but it is also able to infect files that are downloaded by the target, by sending fake software updates for popular software or to infect the target by injecting the payload into visited websites. Some key features of the FinFly LAN include: discovering all computer systems connected to LANs, working in both wired and wireless networks, and remotely installing monitoring solutions through websites visited by the target. FinFly LAN has been used in public hotspots, such as coffee shops, and in the hotels of targets.[16]

- FinFly Web: software which can deploy remote monitoring solutions on a target system through websites. FinFly Web is designed to provide remote and covert infection of a target system by using a wide range of web-based attacks. FinFly Web provides a point-and-click interface, enabling the agent to easily create a custom infection code according to selected modules. It provides fully-customizable web modules, it can be covertly installed into every website and it can install the remote monitoring system even if only the email address is known.[17]

- FinFly ISP: hardware or software which deploys a remote monitoring solution on a target system through an ISP network. FinFly ISP can be installed inside the Internet Service Provider Network, it can handle all common protocols and it can select targets based on their IP address or Radius Logon Name. Furthermore, it can hide remote monitoring solutions in downloads by targets, it can inject remote monitoring solutions as software updates and it can remotely install monitoring solutions through websites visited by the target.[18]

Although FinFisher is supposed to be used for “lawful interception”, it has gained notoriety for targeting human rights activists.[19] According to Morgan Marquis-Boire, a security researcher and technical advisor at the Munk School and a security engineer at Google, FinSpy has been used in Ethiopia to target an opposition group called Ginbot.[20] Researchers have argued that FinFisher has been sold to Bahrain's government to target activists, and such allegations were based on an examination of malicious software which was emailed to Bahraini activists.[21] Privacy International has argued that FinFisher has been deployed in Turkmenistan, possibly to target activists and political dissidents.[22]

Many questions revolving around the use of FinFisher and its “remote monitoring solutions” remain vague, as there is currently inadquate proof of whether this spyware is being used to target individuals by law enforcement agencies in the countries where command and control servers have been found, such as India.[23] However, FinFisher's brochures which were circulated in the ISS world trade shows and leaked by WikiLeaks do reveal some confirmed facts: Gamma International claims that its FinFisher products are capable of taking control of target computers, of capturing encrypted data and of evading mainstream anti-virus software.[24] Such products are exhibited in the world's largest surveillance trade show and probably sold to law enforcement agencies around the world.[25] This alone unveils a concerning fact: spyware which is so sofisticated that it even evades encryption and anti-virus software is currently in the market and law enforcement agencies can potentially use it to target activists and anyone who does not comply with social conventions.[26] A few months ago, two Indian women were arrested after having questioned the shutdown of Mumbai for Shiv Sena patriarch Bal Thackeray's funeral.[27] Thus, it remains unclear what type of behaviour is targeted by law enforcement agencies and whether spyware, such as FinFisher, would be used in India to track individuals without a legally specified purpose.

Furthermore, India lacks privacy legislation which could safeguard individuals from potential abuse, while sections 66A and 69 of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008, empower Indian authorities with extensive surveillance capabilites.[28] While it remains unclear if Indian law enforcement agencies are using FinFisher spy products to unlawfully target individuals, it is a fact that FinFisher control and command servers have been found in India and that, if used, they could potentially have severe consequences on individuals' right to privacy and other human rights.[29]

The Myth of Harmless Metadata

Over the last months, it has been reported that the Central Monitoring System (CMS) is being implemented in India, through which all telecommunications and Internet communications in the country are being centrally intercepted by Indian authorities. This mass surveillance of communications in India is enabled by the omission of privacy legislation and Indian authorities are currently capturing the metadata of communications.[30]

Last month, Edward Snowden leaked confidential U.S documents on PRISM, the top-secret National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance programme that collects metadata through telecommunications and Intenet communications. It has been reported that through PRISM, the NSA has tapped into the servers of nine leading Internet companies: Microsoft, Google, Yahoo, Skype, Facebook, YouTube, PalTalk, AOL and Apple.[31] While the extent to which the NSA is actually tapping into these servers remains unclear, it is certain that the NSA has collected metadata on a global level.[32] Yet, the question of whether the collection of metadata is “harmful” remains ambiguous.

According to the National Information Standards Organization (NISO), the term “metadata” is defined as “structured information that describes, explains, locates or otherwise makes it easier to retrieve, use or manage an information resource”. NISO claims that metadata is “data about data” or “information about information”.[33] Furthermore, metadata is considered valuable due to its following functions:

- Resource discovery

- Organizing electronic resources

- Interoperability

- Digital Identification

- Archiving and preservation

Metadata can be used to find resources by relevant criteria, to identify resources, to bring similar resources together, to distinguish dissimilar resources and to give location information. Electronic resources can be organized through the use of various software tools which can automatically extract and reformat information for Web applications. Interoperability is promoted through metadata, as describing a resource with metadata allows it to be understood by both humans and machines, which means that data can automatically be processed more effectively. Digital identification is enabled through metadata, as most metadata schemes include standard numbers for unique identification. Moreover, metadata enables the archival and preservation of large volumes of digital data.[34]

Surveillance projects, such as PRISM and India's CMS, collect large volumes of metadata, which include the numbers of both parties on a call, location data, call duration, unique identifiers, the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number, email addresses, IP addresses and browsed webpages.[35] However, the fact that such surveillance projects may not have access to content data might potentially create a false sense of security.[36] When Microsoft released its report on data requests by law enforcement agencies around the world in March 2013, it revealed that most of the disclosed data was metadata, while relatively very little content data was allegedly disclosed.[37]

imilarily, Google's transparency report reveals that the company disclosed large volumes of metadata to law enforcement agencies, while restricting its disclosure of content data.[38]

Such reports may potentially provide a sense of security to the public, as they reassure that the content of personal emails, for example, has not been shared with the government, but merely email addresses – which might be publicly available online anyway. However, is content data actually more “harmful” than metadata? Is metadata “harmless”? How much data does metadata actually reveal?

The Guardian recently published an article which includes an example of how individuals can be tracked through their metadata. In particular, the example explains how an individual is tracked – despite using an anonymous email account – by logging in from various hotels' public Wi-Fi and by leaving trails of metadata that include times and locations. This example illustrates how an individual can be tracked through metadata alone, even when anonymous accounts are being used.[39]

Wired published an article which states that metadata can potentially be more harmful than content data because “unlike our words, metadata doesn't lie”. In particular, content data shows what an individual says – which may be true or false – whereas metadata includes what an individual does. While the validity of the content within an email may potentially be debateable, it is undeniable that an individual logged into specific websites – if that is what that individuals' IP address shows. Metadata, such as the browsing habits of an individual, may potentially provide a more thorough and accurate profile of an individual than that individuals' email content, which is why metadata can potentially be more harmful than content data.[40]

Furthermore, voice content is hard to process and written content in an email or chat communication may not always be valid. Metadata, on the other hand, provides concrete patterns of an individuals' behaviour, interests and interactions. For example, metadata can potentially map out an individuals' political affiliation, interests, economic background, institution, location, habits and the people that individual interacts with. Such data can potentially be more valuable than content data, because while the validity of email content is debateable, metadata usually provides undeniable facts. Not only is metadata more accurate than content data, but it is also ideally suited to automated analysis by a computer. As most metadata includes numeric figures, it can easily be analysed by data mining software, whereas content data is more complicated.[41]

FinFisher products, such as FinFly LAN, FinFly Web and FinFly ISP, provide solid proof that the collection of metadata can potentially be “harmful”. In particular, FinFly LAN can be deployed in a target system in a local area network (LAN) by infecting files that are downloaded by the target, by sending fake software updates for popular software or by infecting the payload into visited websites. The fact that FinFly LAN can remotely install monitoring solutions through websites visited by the target indicates that metadata alone can be used to acquire other sensitive data.[42]

FinFly Web can deploy remote monitoring solutions on a target system through websites. Additionally, FinFly Web can be covertly installed into every website and it can install the remote monitoring system even if only the email address is known.[43] FinFly ISP can select targets based on their IP address or Radius Logon Name. Furthermore, FinFly ISP can remotely install monitoring solutions through websites visited by the target, as well as inject remote monitoring solutions as software updates.[44] In other words, FinFisher products, such as FinFly LAN, FinFly Web and FinFly ISP, can target individuals, take control of their computers and their data, and capture even encrypted data and communications with the help of metadata alone.

The example of FinFisher products illustrates that metadata can potentially be as “harmful” as content data, if acquired unlawfully and without individual consent.[45] Thus, surveillance schemes, such as PRISM and India's CMS, which capture metadata without individuals' consent can potentially pose a major threat to the right to privacy and other human rights.[46] Privacy can be defined as the claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine when, how and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.[47] Furthermore, privacy is at the core of human rights because it protects individuals from abuse by those in power.[48] The unlawful collection of metadata exposes individuals to the potential violation of their human rights, as it is not transparent who has access to their data, whether it is being shared with third parties or for how long it is being retained.

It is not clear if Indian law enforcement agencies are actually using FinFisher products, but the Citizen Lab did find FinFisher command and control servers in the country which indicates that there is a high probability that such spyware is being used.[49] This probability is highly concerning not only because the specific spy products have such advanced capabilities that they are even capable of capturing encrypted data, but also because India currently lacks privacy legislation which could safeguard individuals.

Thus, it is recommended that Indian law enforcement agencies are transparent and accountable if they are using spyware which can potentially breach their citizens' human rights and that privacy legislation is enacted into law. Lastly, it is recommended that all surveillance technologies are strictly regulated with regards to the protection of human rights and that Indian authorities adopt the principles on communication surveillance formulated by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Privacy International.[50] The above could provide a decisive first step in ensuring that India is the democracy it claims to be.

[1]. Robert Anderson (2013), “Wondering What Harmless 'Metadata' Can Actually Reveal? Using Own Data, German Politician Shows Us”, The CSIA Foundation, http://bit.ly/1cIhu7G

[2]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, http://bit.ly/fnkGF3

[3]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, “You Only Click Twice: FinFisher's Global Proliferation”, The Citizen Lab, 13 March 2013, http://bit.ly/YmeB7I

[4]. Michael Lewis, “FinFisher Surveillance Spyware Spreads to Smartphones”, The Star: Business, 30 August 2012, http://bit.ly/14sF2IQ

[5]. Marcel Rosenbach, “Troublesome Trojans: Firm Sought to Install Spyware Via Faked iTunes Updates”, Der Spiegel, 22 November 2011, http://bit.ly/14sETVV

[6]. Intercept Review, Mozilla to Gamma: stop disguising your FinSpy as Firefox, 02 May 2013, http://bit.ly/131aakT

[7]. Intercept Review, LI Companies Review (3) – Gamma, 05 April 2012, http://bit.ly/Hof9CL

[8]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying, Citizen Lab and Canada Centre for Global Security Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, 01 May 2013, http://bit.ly/ZVVnrb

[9]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, “You Only Click Twice: FinFisher's Global Proliferation”, The Citizen Lab, 13 March 2013, http://bit.ly/YmeB7I

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying, Citizen Lab and Canada Centre for Global Security Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, 01 May 2013, http://bit.ly/ZVVnrb

[12]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, “You Only Click Twice: FinFisher's Global Proliferation”, The Citizen Lab, 13 March 2013, http://bit.ly/YmeB7I

[13]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinSpy: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/zaknq5

[14]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinSpy Mobile: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/19pPObx

[15]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly USB: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/1cJSu4h

[16]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly LAN: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/14J70Hi

[17]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly Web: Remote Monitoring & Intrusion Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/19fn9m0

[18]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly ISP: Remote Monitoring & Intrusion Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/13gMblF

[19]. Gerry Smith, “FinSpy Software Used To Surveil Activists Around The World, Reports Says”, The Huffington Post, 13 March 2013, http://huff.to/YmmhXI

[20]. Jeremy Kirk, “FinFisher Spyware seen Targeting Victims in Vietnam, Ethiopia”, Computerworld: IDG News, 14 March 2013, http://bit.ly/14J8BwW

[21]. Reporters without Borders: For Freedom of Information (2012), The Enemies of the Internet: Special Edition: Surveillance, http://bit.ly/10FoTnq

[22]. Privacy International, FinFisher Report, http://bit.ly/QlxYL0

[23]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, “You Only Click Twice: FinFisher's Global Proliferation”, The Citizen Lab, 13 March 2013, http://bit.ly/YmeB7I

[24]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinSpy: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/zaknq5

[25]. Adi Robertson, “Paranoia Thrives at the ISS World Cybersurveillance Trade Show”, The Verge, 28 December 2011, http://bit.ly/tZvFhw

[26]. Gerry Smith, “FinSpy Software Used To Surveil Activists Around The World, Reports Says”, The Huffington Post, 13 March 2013, http://huff.to/YmmhXI

[27]. BBC News, “India arrests over Facebook post criticising Mumbai shutdown”, 19 November 2012, http://bbc.in/WoSXkA

[28]. Indian Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, The Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008, http://bit.ly/19pOO7t

[29]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying, Citizen Lab and Canada Centre for Global Security Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, 01 May 2013, http://bit.ly/ZVVnrb

[30]. Phil Muncaster, “India introduces Central Monitoring System”, The Register, 08 May 2013, http://bit.ly/ZOvxpP

[31]. Glenn Greenwald & Ewen MacAskill, “NSA PRISM program taps in to user data of Apple, Google and others”, The Guardian, 07 June 2013, http://bit.ly/1baaUGj

[32]. BBC News, “Google, Facebook and Microsoft seek data request transparency”, 12 June 2013, http://bbc.in/14UZCCm

[33]. National Information Standards Organization (2004), Understanding Metadata, NISO Press, http://bit.ly/LCSbZ

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. The Hindu, “In the dark about 'India's PRISM'”, 16 June 2013, http://bit.ly/1bJCXg3 ; Glenn Greenwald, “NSA collecting phone records of millions of Verizon customers daily”, The Guardian, 06 June 2013, http://bit.ly/16L89yo

[36]. Robert Anderson, “Wondering What Harmless 'Metadata' Can Actually Reveal? Using Own Data, German Politician Shows Us”, The CSIA Foundation, 01 July 2013, http://bit.ly/1cIhu7G

[37]. Microsoft: Corporate Citizenship, 2012 Law Enforcement Requests Report,http://bit.ly/Xs2y6D

[38]. Google, Transparency Report, http://bit.ly/14J7hKp

[39]. Guardian US Interactive Team, A Guardian Guide to your Metadata, The Guardian, 12 June 2013, http://bit.ly/ZJLkpy

[40]. Matt Blaze, “Phew, NSA is Just Collecting Metadata. (You Should Still Worry)”, Wired, 19 June 2013, http://bit.ly/1bVyTJF

[41]. Ibid.

[42]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly LAN: Remote Monitoring & Infection Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/14J70Hi

[43]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly Web: Remote Monitoring & Intrusion Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/19fn9m0

[44]. Gamma Group, FinFisher IT Intrusion, FinFly ISP: Remote Monitoring & Intrusion Solutions, WikiLeaks: The Spy Files, http://bit.ly/13gMblF

[45]. Robert Anderson, “Wondering What Harmless 'Metadata' Can Actually Reveal? Using Own Data, German Politician Shows Us”, The CSIA Foundation, 01 July 2013, http://bit.ly/1cIhu7G

[46]. Shalini Singh, “India's surveillance project may be as lethal as PRISM”, The Hindu, 21 June 2013, http://bit.ly/15oa05N

[47]. Cyberspace Law and Policy Centre, Privacy, http://bit.ly/14J5u7W

[48]. Bruce Schneier, “Privacy and Power”, Schneier on Security, 11 March 2008, http://bit.ly/i2I6Ez

[49]. Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton, For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying, Citizen Lab and Canada Centre for Global Security Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, 01 May 2013, http://bit.ly/ZVVnrb

[50]. Elonnai Hickok, “Draft International Principles on Communications Surveillance and Human Rights”, The Centre for Internet and Society, 16 January 2013, http://bit.ly/XCsk9b