Big Data Governance Frameworks for 'Data Revolution for Sustainable Development'

A key component of the process to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals is the call for a global 'data revolution' to better understand, monitor, and implement development interventions. Recently there has been several international proposals to use big data, along with reconfigured national statistical systems, to operationalise this 'data revolution for sustainable development.' This analysis by Meera Manoj highlights the different models of collection, management, sharing, and governance of global development data that are being discussed.

1. What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

2. The Need for a Data Revolution

3. Big Data: Characteristics and Use for Development

3.1. Characteristics of Big Data

3.2. Using Big Data for Development

4. Sustainable Development and Data Rights

5. Governance Frameworks Proposed

5.1. UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network

5.2. The UN DATA Revolution Group

5.3. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development

5.4. The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development of Data

5.5. The World Economic Forum (WEF)

5.6. Dr. Julia Lane - A Quadruple Data Helix

5.7. Data Pop Alliance

6. Conclusion

7. Endnotes

Speaking on Big Data, Dan Ariely commented that, "Everyone talks about it, nobody really knows how to do it, and everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so everyone claims they are doing it" [1]. This offers a useful insight into the lack of adequate discourse on the kind of governance and accountability frameworks that are needed to facilitate the developmental, sustainable, and responsible uses of big data.

In light of the recent international proposals to use big data to track the Sustainable Development Goals, this paper highlights the different models of management, sharing, and governance of data that are being discussed, and concurrently, how they conceptualise the various rights around big data and how are they to be protected.

1. What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

The Sustainable Development Goals, otherwise known as the Global Goals, build on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Adopted on 1 January 2016, these universally applicable 17 goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, seek to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities, tackle climate change and address a range of social needs like education, health, social protection and job opportunities over the next 15 years [2].

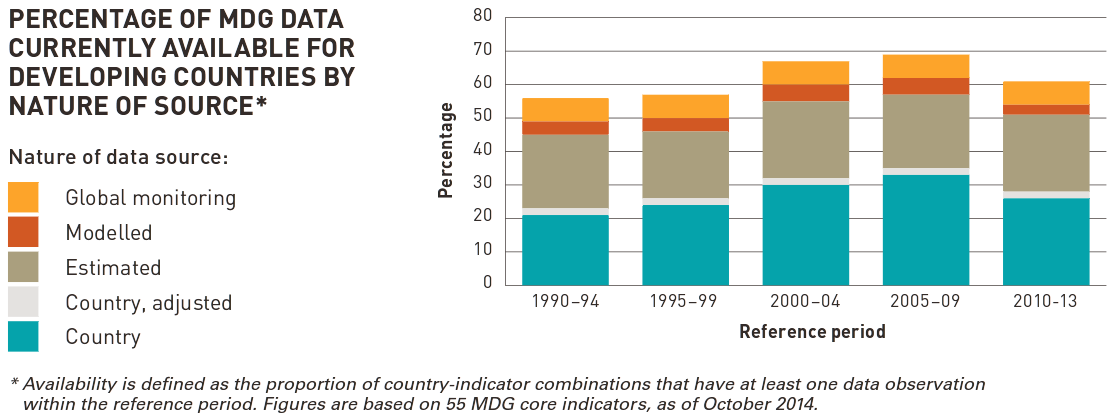

Source: UN Data Revolution Group, A World that Counts, 2014, p.12.

2. The Need for a Data Revolution

An overwhelming cause of concern regarding the precursor to the SDGs, the MDGs, is the data unavailability to monitor their progress. For instance, the figure below indicates that there is no five-year period when the availability of MDG related data is more than 70% of what is required. Entire groups of people and key issues remain invisible [3]. Lack of data is not only a problem for global statisticians, but also for people whose needs and demands remain invisible due to lack of quantitative representation of the same. For instance, the incidences of gender related crimes when not recorded could lead to a misconception on the achievement of the MDG of gender equality.

Source: UN, Sustainable Development Goals.

As the new goals (SDGs) cover a wider range of issues it is clear that a far higher level of detail is required. To this effect the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the post-2015 agenda has called for a "data revolution for sustainable development" [4].

The world is experiencing a Data Revolution and a "data deluge." One estimate has it that 90% of the data in the world has been created in the last 2 years. As Eric Schmidt of Google in 2010 famously said, "There were 5 exabytes of information created between the dawn of civilization through 2003, but that much information is now created every 2 days [5].

In its report A World that Counts, the UN Data Revolution Group defines the data revolution as an explosion in the volume of data, the speed with which data are produced, the number of producers of data, the dissemination of data, and the range of things on which there is data, coming from new technologies such as mobile phones and the “internet of things”, and from other sources, such as qualitative data, citizen-generated data and perceptions data [6].

This data revolution in the context of sustainable development has been defined by the UN Secretary General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group (IEAG) as follows:

[T]he integration of data coming from new technologies with traditional data in order to produce relevant high‐quality information with more details and at higher frequencies to foster and monitor sustainable development. This revolution also entails the increase in accessibility to data through much more openness and transparency, and ultimately more empowered people for better policies, better decisions and greater participation and accountability, leading to better outcomes for the people and the planet [7].

The majority of such “data coming from new technologies” is what can be called big data. It is data being generated in real-time, in high velocity and volume, in a variety of forms and formats, and on an increasing range of phenomenon that are being mediated by digital technologies – from governance to human communication. Further, a good part of such big data is not about the content of the phenomenon concerned but about its process – for example, Call Detail Records are generated for each mobile phone call a person makes and it contains data about the process of the call (time, location, duration, recipient, etc.) but not about the content of the call. Big data about various governmental and human processes are becoming a crucial instrument for documenting and monitoring of the same.

3. Big Data: Characteristics and Use for Development

3.1. Characteristics of Big Data

The simplest definition of big data is that it is a dataset of more than 1 petabyte. The US Bureau of Labour Statistics terms it to be non-sampled data, characterized by the creation of databases from electronic sources whose primary purpose is something other than statistical inference [8].

The characteristics which broadly distinguish Big Data are sometimes called the “3 V’s”: more volume, more variety and higher rates of velocity [9]. Big data sources generally share some or all of these features [10]:

- Digitally generated,

- Passively produced,

- Automatically collected,

- Geographically or temporally trackable, and

- Continuously analysed.

Increasingly, Big Data is recognised as creating "new possibilities for international development" [11]. It could provide faster, cheaper, more granular data and help meet growing and changing demands. It was claimed, for example, that "Google knows or is in a position to know more about France than INSEE" [12], its highly resourceful national statistical agency. To illustrate, Global Pulse gives the example of a hypothetical small household facing soaring commodity prices, particularly food and fuel [13]. They have the options of:

- Getting part of their food at a nearby World Food Programme distribution centre,

- Reducing mobile usage,

- Temporarily taking their children out of school,

- Calling a health hotline when children show signs of malnutrition related diseases, and

- Venting about their frustration on social media.

Such a systemic shock of food insecurity will prompt thousands of households to react in roughly similar ways. These collective behavioural changes may show up in different digital data sources:

- WFP might record that it serves twice as many meals a day,

- The local mobile operator may see reduced usage,

- UNICEF data may indicate that school attendance has dropped,

- Health hotlines might see increased volumes of calls reporting malnutrition, and

- Tweets mentioning the difficulty to “afford food” might begin to rise.

Thus the power of real-time, digital data to predict paths for development is immense. Amassing such a large volume of data which tracks practically every aspect of social behavious can revolutionize the field of official statistics and policy making.

Two points to be noted are: 1) all these data sources are not available for comparison in the real-time by default, so one task before using big data in developmental work is to make data from different sources available across agencies and make them comparable, and 2) finding repeating patterns within large data sets, sourced from varied origins, can not only allow for monitoring but also (statistically) predicting future possibilities and implications for development action.

3.2. Using Big Data for Development

There are several international organizations attempting to use such data.

Global Pulse, a United Nations initiative, launched by the Secretary-General in 2009, seeks to leverage innovations in digital data, rapid data collection and analysis to help decision-makers gain a real-time understanding of how crises impact vulnerable populations. To this end, Global Pulse is establishing an integrated, global network of Pulse Labs, anchored in Pulse Lab New York, to pilot the approach at country level [14].

The Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics, created in May 2014, pursuant to Statistical Commission, makes an inventory of ongoing activities and examples regarding the use of big data, addresses concerns related to methodology, human resources, quality and confidentiality, and develops guidelines on classifying various types of big data sources [15].

There have been applications even on a national and individual level. For instance, in 2013, various sources reported that the CIA had admitted to the “full monitoring of Facebook, Twitter, and other social networks” to identify links between events and sequences or paths leading to national security threats, ultimately leading to forecasting future activities and events [16].

In the field of conflict prevention is the emerging applications to map and analyse unstructured data generated by politically active Internet use by academics, activists, civil society organizations, and even general citizens. In reference to Iran’s post-election crisis beginning in 2009, it is possible to detect web-based usage of terms that reflect a general shift from awareness towards mobilization, and eventually action within the population [17].

The "Big Data, Small Credit" report proposes that financial inclusion can be promoted by allowing consumers with mobile phones to access credit formally as customers [18].

At a national level, the biggest challenge for most big data projects is the limited or restricted access the government agencies have to potential big data sets owned by the private sector [19]. The overall consensus is that Big Data to track SDGs must complement traditional data sources [20]. This is because big data may not always be available for the entire population, or include a diverse enough sample of the population. Moreover most big data projects measure development indicators through a correlation which may not always be correct unlike official data. For instance big data might help in predicting lowered household income through reducing mobile bills while traditional data directly collects income statistics.

In a survey by the Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics [21], it was found that only a few countries have developed a long-term vision for the use of big data, while many are formulating a big data strategy. Most countries have not yet defined business processes for integrating big data sources and results into their work and do not have a defined structure for managing big data projects.

Thus there exists a need to identify a governance framework for big data for sustainable development, not only at national level, but also at the international level.

4. Sustainable Development and Data Rights

Any discussion on governance frameworks would be incomplete without defining the kind of data rights they must seek to protect.

In the famous parable of the six blind men and the elephant they conclude that the elephant is like a wall, snake, spear, tree, fan or rope, depending upon where they touch. Similarly Internet experiences of individual users (what they touch) often contrast drastically with different views (what they conclude) on what would constitute data rights.

The IEAG in its report has identified the following set of data related rights, but has not defined any actual framework or process for ensuring them (yet) [22]:

- Right to be counted,

- Right to an identity,

- Right to privacy and to ownership of personal data,

- Right to due process (for example when data is used as evidence in proceedings, or in administrative decisions),

- Freedom of expression,

- Right to participation,

- Right to non-discrimination and equality, and

- Principles of consent.

Personal data is broadly defined as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable individual" [23]. Often primary data producers (users of services and devices generating data) are unaware of individual privacy infringements [24].

A survey by the Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics found that only a few countries have a specific privacy framework for big data, while most apply the privacy framework for traditional statistics to big data as well [25].

Conventionally, safeguards against the re-use of big data to protect data rights have involved the “anonymization” or “de-identification” of data, to conceal individual identities. Global Pulse, for instance, is putting forth the concept of Data Philanthropy, whereby "corporations take the initiative to anonymize (strip out all personal information) their data sets and provide this data to social innovators to mine the data for insights, patterns and trends in real-time or near real-time" [26]. There however exists a debate on whether data can actually be anonymized effectively. Several state that data can never be effectively de-anonymized due to technological challenges [27]. For instance, when the New York City government released de-anonymised data sets of New York cab drivers were made re-identifiable by approaching a separate method. Within less than 2 hours work, researchers knew which driver drove every single trip in this entire dataset. It would be even be easy to calculate drivers’ gross income, or infer where they live [28].

Even the OECD opines that the current model of limiting identifiability of individuals is unsustainable. It recommends moving towards one where the focus is on transparency around how data is being used, rather than preventing specific types of use, stating that - "research funding agencies and data protection authorities should collaborate to develop an internationally recognized framework code of conduct covering the use of new forms of personal data, particularly those generated via network communication. This framework, built on best practice procedures for consent from data subjects, data sharing and re-use, anonymization methods, etc., could be adapted as necessary for specific national circumstances" [29].

Thus, there is a push for the arguement that the historical approaches to protecting privacy and confidentiality — namely, informed consent and anonymity — no longer hold [30]. Some have even suggested using big data itself to keep track of user permissions for each piece of data to act as a legal contract [31].

There is an overall consensus that any legal or regulatory mechanisms set up to mobilise the 'data revolution for sustainable development' should protect the data rights of the people [32], without any clear agreement on what these rights may be.

5. Governance Frameworks Proposed

A largely unanswered question that is posed in light of the emerging consensus on the use of Big Data for monitoring SDGs is within what sort of governance frameworks these data collection and analysis methods will operate. Methods of collection and the key actors involved in data analysis, management, storage and coordination. The role of NGOs and CSOs, if any, within these systems must be delineated. Certain key global organizations and eminent researchers have suggested the following models.

5.1. UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network

In 2012, the UN Secretary-General launched the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) to mobilize global scientific and technological expertise to promote practical problem solving for sustainable development, including the design and implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [33]. It has proposed the following.

Collection

The Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (IAEGSDG) and the United Nations Statistical Commission are to establish roadmaps for strengthening specific data collection tools that enable the monitoring of SDG indicators.

Analysis

Based on discussions with a large number of statistical offices, including Eurostat, BPS Indonesia, the OECD, the Philippines, the UK, and many others, 100 is recommended to be the maximum number of global indicators to analyse data for which NSOs can report and communicate effectively in a harmonized manner. This conclusion was strongly endorsed during the 46th UN Statistical Commission and the Expert Group Meeting on SDG indicators [34].

Specialist indicators developed by thematic communities must be used for data analysis as they include input and process metrics that are helpful complements to official indicators, which tend to be more outcome-focused. For example, the UN Inter-Agency Group on Child Mortality Estimation has developed a specialist hub responsible for analysing, checking, and improving mortality estimation. This is a leading source for child morality information for both governments and non-governmental actors [35].

Research arms of private companies such as Microsoft Research, IBM research, SAS, and R&D arms of telecom companies could directly partner with official statistical systems to share sophisticated analysing techniques [36].

Management

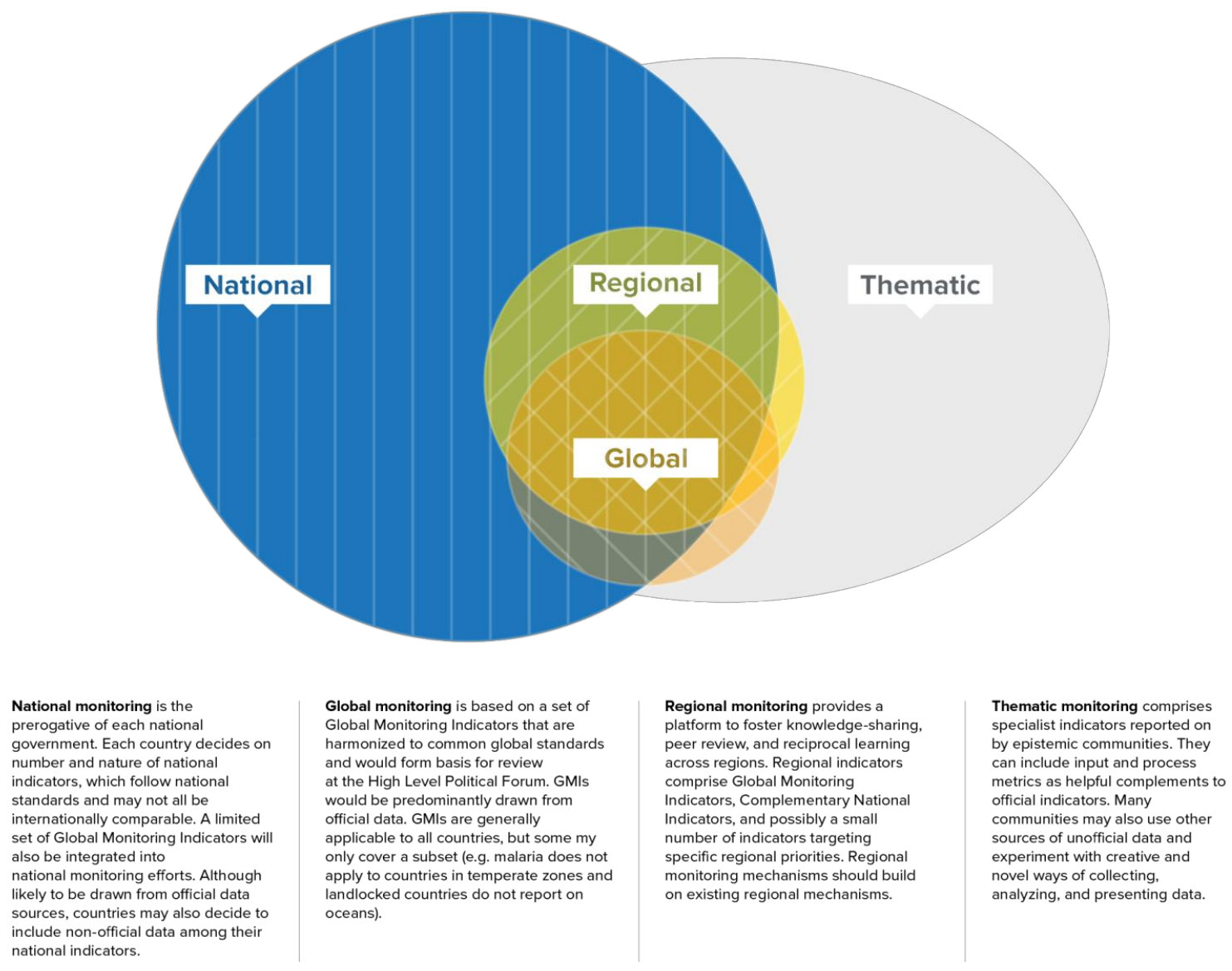

Four levels of monitoring, national, regional, global, and thematic, should be "organized in an integrated architecture" [37].

Countries must decide individually whether official data must be complemented with non-official indicators from big data which can add richness to the monitoring of the SDGs.

Where possible, regional monitoring should build on existing regional mechanisms, such as the Regional Economic Commissions, the Africa Peer Review Mechanism, or the Asia-Pacific Forum on Sustainable Development [38].

To coordinate thematic monitoring under the SDGs, each thematic initiative may have one or more lead specialist agencies or “custodians” as per the IAEG-MDG monitoring processes. Lead agencies would be responsible for convening multi-stakeholder groups, compiling detailed thematic reports, and encouraging ongoing dialogues on innovation. These thematic groups can become testing grounds in launching a data revolution for the SDGs, trialling new measurements and metrics that in time can feed into the global monitoring process with annual reports [39].

Schematic illustration with explanation of the indicators for national, regional, global, and thematic monitoring.

Source: UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals: Launching a Data Revolution for the SDGs, 2015, p.3.

Role of NSOs

Monitoring the SDG agenda will require substantive improvements in national statistical capacity. Assessments of existing capacity to fulfil SDG monitoring expectations must be undertaken and needs be integrated into National Strategies for the Development of Statistics (NSDSs) [40].

Coordination

A Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data must be established and a World Forum on Sustainable Development Data be convened in 2016 to create mechanisms for ongoing collaboration and innovation.

A high-level, powerful group of businesses and states must convene the various data and transparency sustainable development initiatives under one umbrella.

To ensure comparability, Global Monitoring Indicators must be harmonized across countries by one lead technical or specialist agency which will additionally coordinate data standards and collection and provide technical support.

The following table indicates the suggested Lead Agencies for individual SDGs [41].

| Number | Sustainable Development Goal | Lead Agencies |

| 1. | No Poverty | World Bank, UNDP, UNSD, UNICEF, ILO, FAO, UN-Habitat, UNISDR, WHO, CRED, UNFPA, and UN Population Division |

| 2. | No Hunger | FAO, WHO, UNICEF, and Internal Fertilizer Industry Associaton (IFA) |

| 3. | Good Health | WHO, UN Population Division, UNICEF, World Bank, GAVI, UN AIDS, and UN-Habitat |

| 4. | Quality Education | UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank |

| 5. | Gender Equality | UNICEF, UN Women, WHO, UNSD, ILO, UN Population Division, and UNFPA |

| 6. | Clean Water and Sanitation | WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), FAO, UN Water, and UNEP |

| 7. | Renewable Energy | Sustainable Energy for All, IEA, WHO, World Bank, and UNFCC |

| 8. | Good Jobs and Economic Growth | IMF, World Bank, UNSD, and ILO |

| 9. | Innovation and Infrastructure | World Bank, OECD, UNIDO, UNFCC, UNESCO, and ITU |

| 10. | Reduced Inequalities | UNSD, World Bank, and OECD |

| 11. | Sustainable Cities and Communities | UN-Habitat, Global City Indicators Facility, WHO, CRED, UNISDR, FAO, and UNEP |

| 12. | Responsible Consumption | EITI, UNCTAD, UN Global Compact, FAO, UNEP Ozone Secretariat, WBCSD, GRI, IIRC, and Global Compact |

| 13. | Climate Action | OECD DAC, UNFCCC, and IEA |

| 14. | Life below Water | UNEP-WCMC, IUCN, and FMC |

| 15. | Life on Land | FAO, UNEP, IUCN, and UNEP- WCMC |

| 16. | Peace and Justice | UNODC, WHO, UNOCHA, UNCHR, IOM, OCHA, OECD, UN Global Compact, EITI, UNCTAD, UNICEF, UNESCO, and Transparency International |

| 17. | Partnership for the Goals | BIS, IASB, IFRS, IMF, WIPO, WTO, UNSD, OECD, World Bank, OECD DAC, and SDSN |

5.2. The UN DATA Revolution Group

The group constituted by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in August 2014, is an Independent Expert Advisory Group with the aim of making concrete recommendations on bringing about a 'data revolution for sustainable development' [42]. In its report, A World that Counts, it makes the following recommendations [43].

Collection

Clear standards on data collection methods must be developed based on the UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics. Periodic audits must be conducted by professional and independent third parties to ensure data quality.

Governments, civil society, academia and the philanthropic sector must work together strengthening statistical literacy so that all people have capacity to input into and evaluate the quality of data.

Social entrepreneurs, private sector, academia, media, civil society and other individuals and institutions must be engaged globally with incentives (prizes, data challenges) to encourage data sharing.

Analysis

A SDGs Analysis and Visualisation Platform is to be set up for fostering private-public partnerships and community-led peer-production efforts for data analysis.

A dashboard on ”the state of the world” will engage the UN, think-tanks, academics and NGOs in analysing, and auditing data.

Academics and scientists are to analyse data to provide long-term perspectives, knowledge and data resources at all levels.

The “Global Forum of SDG-Data Users” will ensure feedback loops between data producers, processors and users to improve the usefulness of data and information produced.

A “SDGs data lab” to support the development of a first wave of SDG indicators is to be established mobilizing key public, private and civil society data providers, academics and stakeholders working with the Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Storage

A “world statistics cloud” will store data and metadata produced by different institutions but according to common standards, rules and specifications.

Role of NSOs

Civil society organisations must share data and processing methods with private and public counterparts on the basis of agreements. They must hold governments and companies accountable using evidence on the impact of their actions, provide feedback to data producers, develop data literacy and help communities and individuals generate and use data.

NSOs are the central players of the Data Revolution. Their autonomy must be strengthened to maintain data quality. They must abandon expensive and cumbersome production processes, incorporate new data sources like big data that is human and machine-readable, compatible with geospatial information systems and available quickly enough to ensure that the data cycle matches the decision cycle. Collaborations with the private sector can boost technical and financial investments.

Coordination

Key stakeholders must create a “Global Consensus on Data”, to adopt principles concerning legal, technical, privacy, geospatial and statistical standards. Best practices related to public data such as the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and the G8 Open Data Charter are recommended foundations for such principles.

A UN-led “Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data” is proposed, to coordinate and broker key global public-private partnerships for data sharing [44].

A “World Forum on Sustainable Development Data” and “Network of Data Innovation Networks” will be a converging point for the data ecosystem to share ideas and experiences for improvements, innovation and technology transfer.

5.3. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD)

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an inter-governmental organization that seeks to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people globally. It has made the following proposals [45].

Collection

Data is to be collected from National statistical agencies, national and international researchers and international organisations.

Role of NSOs

By leveraging the expertise of telecommunications companies and software developers, for instance, national statistical systems could potentially reduce costs and improve the availability of data to monitor development goals [46].

Coordination

National Data Forums for Social Science Data must be created for the development of social science data for improved coordination between social scientists, data producers (national statistical agencies, government departments, large private sector businesses and sources undertaking academic direction), and data curators.

Social science research communities must contribute to national plans of action after a needs assessment [47]. Research funding agencies must collaborate at the international level for a common system for referencing datasets in research publications [48].

5.4. The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development of Data

The partnership is a global network of governments, NGOs, and businesses working to strengthen the inclusivity, trust, and innovation in the way that data is used to address the world’s sustainable development efforts [49].

Analysis

There must be a common framework for information processing. At minimum, a simple lexicon must tag each datum specifying:

- What: i.e. the type of information contained in the data,

- Who: the observer or reporter,

- How: the channel through which the data was acquired,

- How much: whether the data is quantitative or qualitative, and

- Where and when: the spatio-temporal granularity of the data.

Analysis of data involves filtering relevant information, summarising keywords and categorising into indicators. This intensive mining of socioeconomic data, known as “reality mining,” can be done by: (1) Continuous analysis of real time streaming data, (2) Digestion of semi-structured and unstructured data to determine perceptions, needs and wants. (3) Real-time correlation of streaming data with slowly accessible historical data repositories.

Use of big data for developmental goals can draw upon all three techniques to various degrees depending on availability of data and the specific needs.

Role of NSOs

NSOs have a pivotal part to play in the data revolution. Countries and organizations believe that big data cannot replace traditional official statistical data as it is based more on perception than facts. To quote Winston Churchill, "Do not trust any statistics that you did not fake yourself."

For instance, a study found that Google Flu Trends, to detect influenza epidemics, predicted nonspecific flu-like respiratory illnesses well but not actual flu. The mismatch was due to popular misconceptions on influenza symptoms. This has important policy implications. Doctors using Google Flu Trends may overstock on flu vaccines or be overly inclined to diagnose normal respiratory illnesses as influenza [50].

However Big Data if understood correctly, can inform where further targeted investigation is necessary and give immediate responses to favourably change outcomes.

5.5. The World Economic Forum (WEF)

The WEF is an International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation. It engages the foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas [51]. In the report titled Big Data, Big Impact: New Possibilities for International Development, it makes the following recommendations [52].

Collection

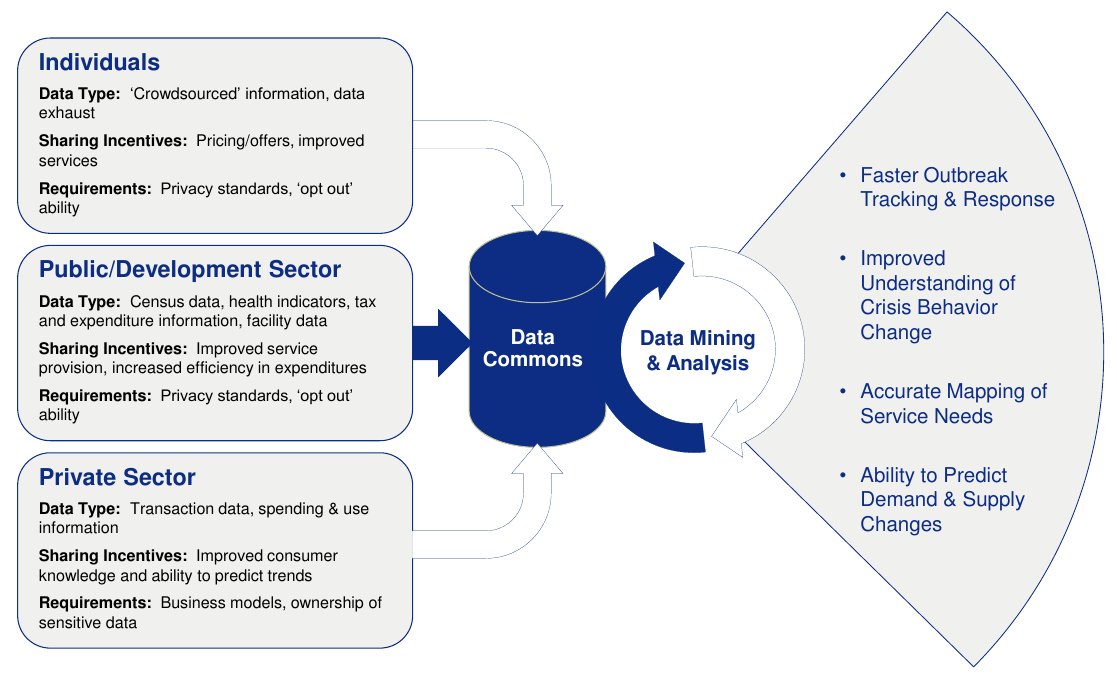

Data production and development actors include individuals, public sector and the private sector. Each produce different kinds of data that have unique requirements. The private sector maintains vast troves of transactional data, much of which is "data exhaust," or data created as a by-product of other transactions. The public sector maintains enormous datasets in the form of census data, health indicators, and tax and expenditure information. The following figure highlights the different kinds of data that each sector collects and what incentives they have to share the data along with requirements to maintain such data.

World Economic Forum - Diagram on Data Commons.

Source: World Economic Forum, Big Data, Big Impact: New Possibilities for International Development, 2012, p.4.

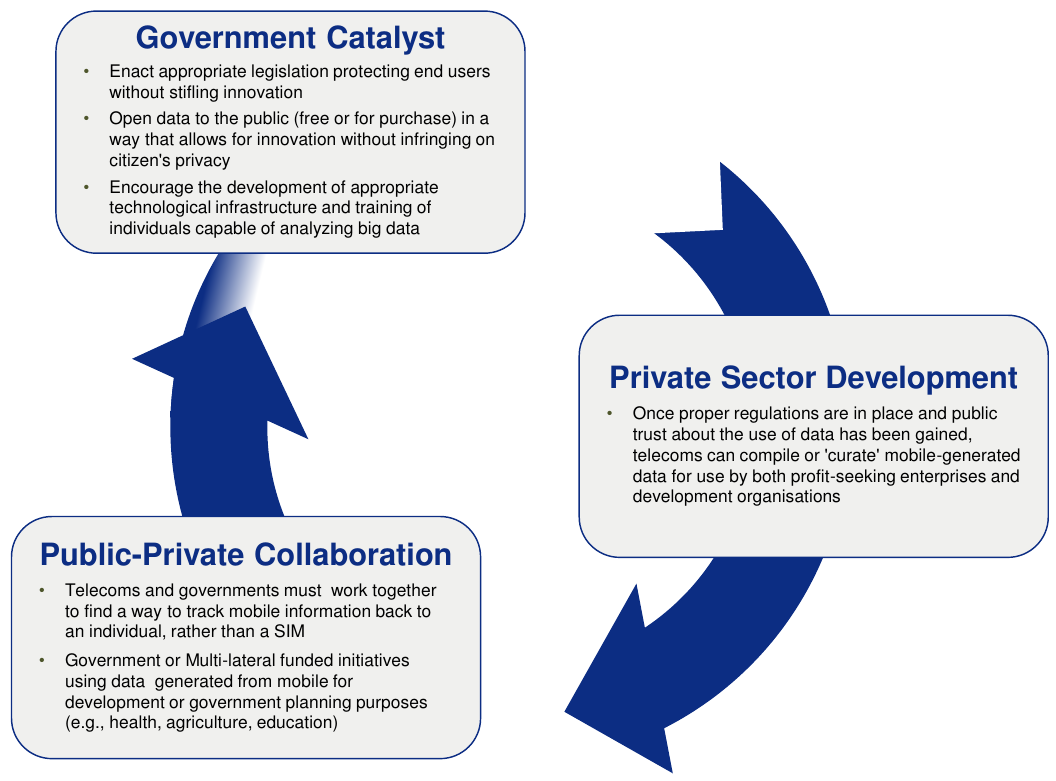

Business models must be created to provide the appropriate incentives for private-sector actors to share data. Such models already exist in the Internet environment. For instance companies in search and social networking profit from products they offer at no charge to end users because the usage data these products generate is valuable to other ecosystem actors. Similar models could be created in garnering Big Data for SDGs. The following flowchart illustrates how different sectors must work together to incentivise data collection and sharing.

World Economic Forum - Diagram on Global Coordination.

Source: World Economic Forum, Big Data, Big Impact: New Possibilities for International Development, 2012, p.7.

5.6. Dr. Julia Lane - A Quadruple Data Helix

Dr. Julia Lane is a Professor in the Wagner School of Public Policy at New York University; and also a Provostial Fellow in Innovation Analytics and a Professor in the Center for Urban Science and Policy [53]. She has done extensive research on the uses of big data. In her paper titled "Big Data for Public Policy: A Quadruple Data Helix," she makes the following suggestions [54].

Collection

In the future there will exist a model of a quadruple data helix for data collection which will have four strands — state and city agencies, universities, private data providers, and federal agencies.i

A new set of institution, city/university data facilities, must be established. These institutions should form the backbone of the quadruple helix, with direct connections to the private sector and to the federal statistical agencies.

Analysis

There is a need for graduate training for non-traditional students, who need to understand how to use data science tools as part of their regular employment. They must identify and capture the appropriate data, understand how data science models and tools can be applied, and determine how associated errors and limitations can be identified from a social science perspective.i

Universities can act as a trusted independent third party to process, store, analyze, and disseminate data. ii

Management

The new infrastructure must ensure that data from disparate sources are collected managed and used in a manner that is informed by end users. There are many technical challenges: disparate data sets must be ingested, their provenance determined, and metadata documented. Researchers must be able to query data sets to know what data are available and how they can be used. And if data sets are to be joined, they must be joined in a scientific manner, which means that workflows need to be traced and managed in such a way that the research can be replicated.

Coordination

The role of State and City agencies is to address immediate policy issues, rather than to build long-term data infrastructures as their mandate is to work with city data than the full spectrum of available data.

5.7. Data-Pop Alliance

Data-Pop Alliance is a global coalition on Big Data and development created by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, MIT Media Lab, and Overseas Development Institute that brings together researchers, experts, practitioners, and activists to promote a people-centred big data revolution through collaborative research, capacity building, and community engagement [55]. It makes the following suggestions.

Collection

The idea of shared responsibility between the public and private sector is a proposed operational principles to create a deliberative space. Mechanisms and legal frameworks must be devised for private companies to share their big data under formalized and stable arrangements instead of being compelled by ad hoc requests from researchers and policymakers.

The media too, could avoid publishing statistical data collected by unexplained methodologies by employing "statistical editors" and disseminate verified information.

Role of NSOs

For official statistics, engaging with Big Data is not a technical consideration but a political obligation. In a two tier system of official and non-official statistics, the public and investors tend to distrust official figures. For instance, the results of the 2010 census in the UK are being disputed on the basis of sewage data.

It is imperative for NSOs to retain, or regain, their primary role as the legitimate custodian of knowledge and creator of a deliberative public space to democratically drive human development [56].

6. Conclusion

The Big data frameworks provide some useful insights on monitoring mechanisms though some questions remain unanswered in each model. Key actors that have been proposed include city and state agencies like NSOs, private companies, social scientists, private individuals and international research agencies. Data analysis can be through public-private collaborations, data philanthropy, and using indicators by thematic communities.

Collection

There appears consensus across models that collection must be effected through public private partnerships while providing incentives.

Analysis

While several methods of analysis have been proposed by the Global Partnership it is unclear on who will be conducting the analysis. The UNSDSN has suggested that it be conducted by academics and scientists with Julia Lane stating it must be through public private partnerships which appear more feasible and transparent.

Role of NSOs

All frameworks agree on the pivotal role of NSOs and acknowledge them as the key players and coordinators at the national level. They must be strengthened financially, technologically and politically. Most frameworks seek to empower national agencies which will coordinate collaborations with the private sector through incentives while protecting personal data.

Coordination

Several international fora have been proposed to enable coordination while there is consensus that the NSOs. A Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, a Global Consensus on Data and a World Forum on Sustainable Development Data have been suggested. UN organizations appear to be suggesting more responsibility for those in the UN framework with UNSDSN giving an extensive list of lead agencies (UNDP, UN Women, Who etc) while the WEF emphasises on the private sector, Data Pop Alliance on NSOs, and Prof. Lane on State and City agencies.

On an international level countries can opt to join international organization that are being setup for the purpose. It remains to be seen whether all countries globally can achieve such a feat in a coordinated manner without infringing on data rights when unanswerable to any set international organization. The burden appears to fall on civil society and market forces within the private sector to regulate this process. For instance when a private sector company starts providing large un-anonymized data sets for government use, the privacy concerns of civil society that result in them opting for the company’s competitor’s more privacy friendly products will result in a regulation through market forces. However these forces may have disparate strengths in different contexts and countries depending on market practices and information asymmetry resulting in the lack of a uniform accountability mechanism.

7. Endnotes

[1] Dan Ariely, Facebook, January 06, 2013, https://www.facebook.com/dan.ariely/posts/904383595868.

[2] United Nations Organizations, 'Sustainable Development Goals' (United Nations Sustainable Development, 26 September 2015), http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/, accessed 6 June 2016.

[3] Data Revolution Group, 'A World that Counts: Mobilising the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development' (November 2014), http://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/A-World-That-Counts2.pdf, accessed 8 June 2016.

[4] High level panel on the post-2015 development agenda , 'A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development'(Post2015hlp,0rg, July 2012), http://www.post2015hlp.org/, accessed 8 June 2016.

[5] Gary King, 'Ensuring the Data-Rich Future of the Social Sciences' [2011] 3(2) Science, http://gking.harvard.edu/files/datarich.pdf, accessed 8 June 2016.

[6] See [3].

[7] Ibid.

[8] Michael Horrigan, 'Big Data: A Perspective from the BLS' (Amstatorg, 1 January 2013) http://magazine.amstat.org/blog/2013/01/01/sci-policy-jan2013/, accessed 4 June 2016.

[9] UN Global Pulse, 'Big Data for Development: Challenges & Opportunities' (6 May 2012) http://www.unglobalpulse.org/sites/default/files/BigDataforDevelopment-UNGlobalPulseJune2012.pdf, accessed 5 June 2016.

[10] Emmanuel Letouzé and Johannes Jütting, 'Official Statistics, Big Data and Human Development: Towards a New Conceptual and Operational Approach' (2014) 12(3), Data-Pop Alliance White papers Series, https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/events-documents/5161.pdf, accessed 4 June 2016.

[11] See [9].

[12] See [10].

[13] See [9].

[14] UN Global Pulse, 'About: United Nations Global Pulse' (2016) http://www.unglobalpulse.org/about-new, accessed 7 June 2016.

[15] UN Stats, 'Global Working Group' (2014) http://unstats.un.org/unsd/bigdata/, accessed 8 June 2016.

[16] New York City Press Release, ‘Mayor Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Kelly and Microsoft Unveil New, State-of-the-Art Law Enforcement Technology that Aggregates and Analyzes Existing Public Safety Data in Real Time to Provide a Comprehensive View of Potential Threats and Criminal Activity’ (New York City, 8 August 2012), http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/291-12/mayor-bloomberg-police-commissioner-kelly-microsoft-new-state-of-the-art-law, accessed 2 July 2016.

[17] Francesco Mancini, 'New Technology and the Prevention of Violence and Conflict' (Reliefwebint, April 2013), http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ipi-e-pub-nw-technology-conflict-prevention-advance.pdf, accessed 2 July 2016.

[18] Arjuna Costa, Anamitra Deb, and Michael Kubzansky, 'Big Data, Small Credit: The Digital Revolution and Its Impact on Emerging Market Consumers,' (Omidyar, 3 March 2013) https://www.omidyar.com/sites/default/files/file_archive/insights/Big%20Data,%20Small%20Credit%20Report%202015/BDSC_Digital%20Final_RV.pdf, accessed 2 July 2016.

[19] United Nations Economic and Social Council, 'Report of the Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics' (UN Stats, 3 March 2015), http://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/doc15/2015-4-BigData-E.pdf, accessed 8 June 2016.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] See [3].

[23] OECD, 'OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data' (23 September 1980), http://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/oecdguidelinesontheprotectionofprivacyandtransborderflowsofpersonaldata.htm, accessed 29 May 2016.

[24] Amir Efrati, ''Like' Button Follows Web Users' (WSJ, 18 May 2011) http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704281504576329441432995616, accessed 23 May 2016.

[25] See [15].

[26] Robert Kirkpatrick, 'Data Philanthropy: Public and Private Sector Data Sharing for Global Resilience' (UN Global Pulse, 16 September 2011), http://www.unglobalpulse.org/blog/data-philanthropy-public-private-sector-data-sharing-global-resilience, accessed 4 June 2016.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Arvind Narayanan, 'No silver bullet: De-identification still doesn't work' (1 April 2016), http://randomwalker.info/publications/no-silver-bullet-de-identification.pdf, accessed 3 July 2016.

[29] OECD Global Science Forum, 'New Data for Understanding the Human Condition: International Perspectives,' (February 2013) http://www.oecd.org/sti/sci-tech/new-data-for-understanding-the-human-condition.pdf, accessed 2 June 2016.

[30] S. Barocas, 'The Limits of Anonymity and Consent in the Big Data Age,' in Privacy, Big Data, and the public good: Frameworks for Engagement (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[31] A. Pentland, 'Institutional Controls: The New Deal on Data,' in Privacy, Big Data, and the public good: Frameworks for Engagement (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[32] See [3].

[33] UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 'About Us: Vision and Organization' (2012) http://unsdsn.org/about-us/vision-and-organization/, accessed 2 June 2016.

[34] UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 'Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals: Launching a data revolution for the SDGs' (12 June 2015) http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/150612-FINAL-SDSN-Indicator-Report1.pdf, accessed 4 June 2016.

[35] UNICEF, 'CME Info - Child Mortality Estimates' (2014) http://www.childmortality.org/, accessed 1 June 2016.

[36] See [10].

[37] UNESCO, 'Technical report by the Bureau of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) on the process of the development of an indicator framework for the goals and targets of the post-2015 development agenda' (6 March 2015) http://www.uis.unesco.org/ScienceTechnology/Documents/unsc-post-2015-draft-indicators.pdf, accessed 3 June 2016.

[38] UN, 'The Road to Dignity by 2030: Ending Poverty, Transforming All Lives and Protecting the Planet ' (4 December 2014) http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/reports/SG_Synthesis_Report_Road_to_Dignity_by_2030.pdf, accessed 7 June 2016.

[39] Ibid.

[40] UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 'Data for Development: An Action Plan to Finance the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development' (10 July 2015) http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Data-For-Development-An-Action-Plan-July-2015.pdf, accessed 3 June 2016.

[41] See [34].

[42] UN Data Revolution Group, 'About the Independent Expert Advisory Group' (6 November 2014) http://www.undatarevolution.org/about-ieag/, accessed 4 June 2016.

[43] See [3].

[44] The Partnership has already been established, and it is developing a further framework.

[45] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development), 'The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): About' (2016) http://www.oecd.org/about/, accessed 2 June 2016.

[46] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 'Strengthening National Statistical Systems to Monitor Global Goals' (2015) http://www.oecd.org/dac/POST-2015%20P21.pdf, accessed 1 June 2016.

[47] Ibid.

[48] OECD Global Science Forum, 'New Data for Understanding the Human Condition: International Perspectives' (February 2013) http://www.oecd.org/sti/sci-tech/new-data-for-understanding-the-human-condition.pdf, accessed 2 June 2016.

[49] The Global Partnership On Sustainable Development Data, 'Who We Are: The Data Ecosystem and the Global Partnership' (2016) http://www.data4sdgs.org/who-we-are/, accessed 5 June 2016.

[50] World Economic Forum, 'Big Data, Big Impact: New Possibilities for International Development' (22 January 2012) http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TC_MFS_BigDataBigImpact_Briefing_2012.pdf, accessed 8 June 2016.

[51] World Economic Forum, 'Our Mission: The World Economic Forum' (12 January 2016) https://www.weforum.org/about/world-economic-forum/, accessed 7 June 2016.

[52] See [50].

[53] Julia Lane, Homepage, http://www.julialane.org/.

[54] Julia Lane, 'Big Data for Public Policy: The Quadruple Helix' (2016) 8(1) Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, DOI:10.1002/pam.21921, accessed 1 June 2016.

[55] Data-Pop Alliance, 'Data-Pop Alliance: Our Mission' (May 2014) http://datapopalliance.org/, accessed 1 June 2016.

[56] See [10].

8. Author Profile

Meera Manoj is a law student at the Gujarat National Law University, Gandhinagar and has completed her first year. She is passionate about civil rights, feminism, economics in law and anything involving paneer. She aspires to travel the world and build up a vast library, with unparalleled sections on International Law and Archie comics.