How Web 2.0 responded to Hazare

Social media often fails to give us time to form critical opinions. ‘It mirrored the spectacle that we were being fed by TV channels', says Nishant Shah in an interview with Deepa Kurup. This news was published in the Hindu on April 11, 2011.

By Day Two of the protests at Jantar Mantar, where social activist Anna Hazare was leading a fast-unto-death against corruption, most commentators were drawing fierce parallels with Tahrir Square, and other pro-democracy revolutions in the Middle-East.

Soon enough, the social media angle raised its head. After a quiet Tuesday, when television channels began to “play up” the protests, Wednesday morning saw social media platforms abuzz with chatter. Initiated by campaign organisers, the India Against Corruption team, Facebook profile badges, missed call campaigns and petitions (most notably on online campaign site Avaaz (where over 6.17 lakh have registered support) entered the scene.

In 140 characters, #janlokpal, #annahazare and the less gracious #meranetachorhain began to trend on Twitter. YouTube shows up around 2,000 video results, a lot of which are amateur videos shot by participants.

‘Causes' application requests for “brandishing corruption”, ‘Like'-this-revolution requests and Tweets on how you can indeed weed out the corruption demon with a Re-Tweet, were abound.

But did this social media buzz translate into more people on the ground? Did the Tweets and chain e-mails, that were doing the rounds fairly early on, manage to drive public opinion, or outrage, as in this case? On this, the jury is divided.

Crunching numbers

Even in the Middle-East, where we saw dictators plug social media channels, experts have downplayed the pivotal role attributed to social media. A tool for sharing information, its standalone role in triggering a revolution has been dismissed by many.

In the current context, this is even more difficult to establish because efforts appear to be all too scattered, unlike in Egypt where the ‘We are all Khaled Said' page by Wael Ghonim, appeared to be a focal point of sorts.

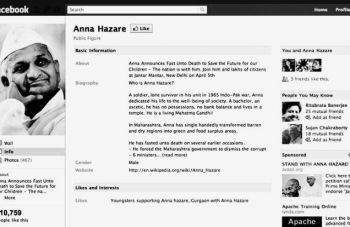

In comparison, a simple search on Facebook reveals over 20 pages that all have around 25,000-30,000 users on-board. Mr. Hazare's Facebook profile page has over 1.3 lakh ‘Likes'.

Gaurav Mishra, social media analyst, pegs the total support at around 15 lakh. Drawing parallels with the citizen activism campaigns that emerged between the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008 and the Lok Sabha elections of 2009 (the former being when social media arrived in India), Mr. Mishra also points out that corruption did go for a Six on Friday (the final day) with IPL4 dominating conversation online.

Nishant Shah, director (research) at the Centre for Internet and Society, points out that while during revolutions, the social media has proved to be a poignant and powerful tool to mobilise resources, last week it emerged that it can not only propagate dubious opinions, but also it often (because it relies on the temporal quality of making things viral) fails to give us time to form critical opinions.

He compares a platform like Avaaz, that mobilised people ‘against corruption', with long-term Ipaidabribe project (using the same digital tools) which actually leads to debate around why corruption is so endemic.

Mirrors TV

Interestingly, as Mr. Shah points out, the social media mirrored the spectacle that people were being fed by TV channels, instead of being a true discursive space of public dialogue. It's now getting clear that they are actually playing out an interesting traction as they supplement each other in bolstering of evidence and participation, he adds.

On the other hand, blogs too were abuzz. However, many did seek to provide deeper perspective, and provided more space for debate and dissent. In fact, progressive blogs even attempted to counter the one-sided commentary provided on traditional visual media.

Click here for the story in the Hindu