Privacy, speech at stake in cyberspace

Internet censorship is becoming a trend, with many countries around the world filtering the Web in varying degrees, writes Leslie D’Monte in Livemint on February 3, 2012.

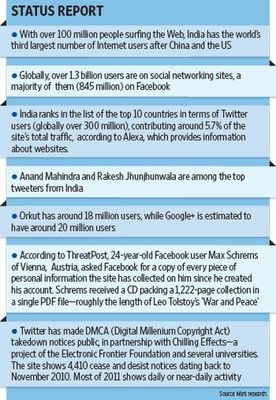

Privacy and freedom of expression are gradually being compromised in cyberspace, say advocacy groups, with social networking sites and Internet companies buckling under pressure from governments to monitor and block “objectionable” content.

Take the case of Twitter Inc., which on 26 January posted on its official blog that “...starting today, we give ourselves the ability to reactively withhold content from users in a specific country—while keeping it available in the rest of the world”. While Twitter reasoned that as it continues to grow internationally, it will have to deal with “countries that have different ideas about the contours of freedom of expression”, activists and bloggers cautioned that the new censorship policies could muffle online freedom.

“The decision of Twitter to censor its content based on the political masters’ wishes in each country is an indication that commercial interests are always higher than democratic interests for these companies. The move of the Indian government to arm-twist the major intermediaries is, therefore, expected to succeed in due course once the initial resistance wears off,” cautioned Na. Vijayashankar, a Bangalore-based e-business consultant and founder secretary of the Cyber Society of India.

In December, minister for communications and information technology (IT) Kapil Sibal said in New Delhi that the Centre had no option but to “evolve guidelines” to ensure that “blasphemous content on the Internet or television is not allowed”, since Internet and social networking sites such as Google Inc., Microsoft Corp., Twitter, Yahoo Inc., and Facebook Inc. failed “to respond to and cooperate with” the government’s request to keep “objectionable” content off their sites.

A few days later, Sibal clarified that “...this government (of the United Progressive Alliance) does not believe in censorship”. And in an interview to Mint on 1 February, Gulshan Rai—head of the elite Indian Computer Emergency Response Team and coordinator of a committee on cyberlaw—said, inter alia, “We value the freedom of speech. We do not interfere there.”

Internet censorship is a rising trend, with approximately 40

countries filtering the Web in varying degrees, including democratic and

non-democratic governments. YouTube and Gmail (both from Google),

BlackBerry maker Research In Motion Ltd, WikiLeaks, Twitter and Facebook

have all been censored, at different times, in China, Iran, Egypt and

other countries.

“The clampdown on online free speech and the roll-out of a multi-tiered

blanket surveillance regime via the draconian IT Act and its associated

rules in India is part of a global trend,” said Sunil Abraham, executive

director of the Centre for Internet and Society. “Big brother

tendencies with the government have found common cause with powerful

rights-holders, who are keen to crack down on intellectual property

rights infringements. This, combined with the dramatic growth of the

surveillance industry, has resulted in civil liberties being undermined

across the world for a variety of pretexts ranging from child porn,

obscenity, hate speech, organized crime, terrorism and piracy.”

Transparency Report website—which logs content removal requests it receives from governments—the Internet company received 67 requests from the Indian government for the removal of 282 content items (such as videos critical of politicians) from YouTube and blogs during July-December 2010. Google said it complied with 22% of the requests. For the January-June 2011 (latest data available) period, Google received 68 content removal requests for 358 items from Indian government agencies. Google complied in 51% cases.

Entangling the user

Even as they face pressure from governments, companies such as Google and Facebook are tweaking their policies to allow for sharing of user data across multiple product offerings. They claim it will give their users a more “intuitive” experience, but advocacy groups say the policies are being altered to give advertisers more bang for the buck at the expense of user privacy.

Google, for instance, is making changes to its privacy policies and terms of service, which take effect from 1 March. “Regulators globally have been calling for shorter, simpler privacy policies—and having one policy covering many different products is now fairly standard across the Web,” said Alma Whitten, Google’s director of privacy, product and engineering, on the official company blog. Google has begun notifying users of these changes since 24 January.

For example, a search for restaurants in Mumbai may throw up Google+ posts or photos that people have shared with other users, or that are in their albums. Usability can be enhanced, for instance, by allowing memos from Google Docs to be read in Gmail, or adding a Gmail contact to a meeting in Google Calendar. Google, according to Whitten, does not sell personal information nor share it externally without permission “except in very limited circumstances like a valid court order”.

Facebook, on its part, introduced its “Timeline” feature in December, which digs up a user’s past and displays it, but does not allow opting out of the service. The feature is being introduced for all 800 million users, around 40 million of whom are in India. Those not accustomed to checking their privacy settings will have a hard time going through the hundreds of messages they’ve posted over the last few years (Facebook was founded in 2004).

The Electronic Privacy Information Center said the launch of Timeline forces more privacy setting changes on Facebook users, “which flies in the face of both privacy and a settlement reached between the firm and the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC)”. On 29 November, Facebook agreed to an FTC order that bars it from “deceiving” consumers about privacy practices and requires it to submit to monitoring for 20 years.

“Privacy is certainly a very serious concern for Internet users. Some of the big brands like Facebook and Google simply have access to too much information about the life of their users, and this information could easily be misused by the brand or wilfully by someone else. Our guidance to consumers and clients is that first and foremost, they should be very conscious of these privacy challenges. If we put out any communication on a social network, it is akin to broadcast communication. By default, choose the tightest privacy setting and then gradually loosen up instead of accepting the default privacy setting of Facebook or Google. Don’t give out information like cellphone number, date of birth...or even names of close relations on social networks,” said Hareesh Tibrewala, joint chief executive officer of Social Wavelength, a company that advises clients on social media strategies.

Mahesh Murthy, founder of digital marketing firm Pinstorm, acknowledged that “in reality, there is virtually no privacy online. Governments and companies try to assure apprehensive citizens about privacy, while at the same time doing everything to destroy it in reality”.

He advises marketers to be upfront about their data collection and management policies, and declare them prominently on their online properties. On an individual level, Murthy takes comfort “in the fact that I could just be one of those 3 billion+ Internet users worldwide with my data a small part of the swarm out there that no one might take a special interest in”.

Electronic police state?

India has a history of exerting pressure on companies for access to communications data. According to Cryptohippie Inc., a provider of communication security services, India ranked 26 among the most policed states in the world in 2010—“one in which every surveillance camera recording, every email sent, every Internet site surfed, every post made, every check written, every credit card swipe, every cellphone ping…are all criminal evidence, and all are held in searchable databases”, according to the company that discontinued the report in 2011, stating that “…most people are defending their ignorance; not much good will come from us repeating ourselves”.

Currently, the Indian Telegraph Act and the IT Act, 2008 (amendments introduced in the IT Act, 2000), give the government the power to monitor, intercept and even block online conversations and websites. Moreover, under section 79 of the IT Intermediary (Rules and Guidelines), 2011, intermediaries—telcos, Internet services providers, network services providers, search engines, cyber cafes, Web-hosting companies, online auction portals and online payment sites—are mandated to exercise “due diligence” and advise users not to share/distribute information violative of the law or a person’s privacy and rights. Intermediaries are expected to act on a complaint within 36 hours of receiving it, and remove such content when warranted. In case the intermediary doesn’t find the content objectionable, the matter will have to be contested in a court of law.

“The Indian government can, and should, monitor conversations and websites if it believes the content can harm the security, defence, sovereignty and integrity of the country,” maintained Pavan Duggal, a Supreme Court lawyer and a cyberlaw expert, but wondered how it would go about implementing the task of monitoring conversation on an unstructured Internet. “The intention is good, but the path is not clear,” said Duggal, who envisions a lot of cases being filed against misuse of these laws.

“While the affected party can lodge a complaint with the intermediary, removal has to follow a due process, which should include suitable documentary evidence placed by the party. There should be a process of examination through an ombudsman, a process of arbitration where the request is disputed or a court order as may be required on a case to case basis,” said Vijayashankar of the Cyber Society of India.

The original was published in Livemint on 3 February 2012. Sunil Abraham was quoted in it.