Beyond the Searchlight

Pulse reader Google India VP and MD Rajan Anandan at the release of its urban Indian voters study. Picture by Sanjay Rawat

Should we be wary of Google’s all-pervasiveness?

Pulse reader Google India VP and MD Rajan Anandan at the release of its urban Indian voters study. Picture by Sanjay Rawat

This article Debarshi Dasgupta was published in the Outlook on October 23, 2013. Sunil Abraham is quoted.

Search Google

Some queries to type in the window

- Is what is good for Google good for India, especially after Brazil and the EU question its actions?

- Are politicians sending out the right signals by associating with Google’s initiatives?

- Is Google directing the internet intellectual discourse in a way that will benefit it?

- Does Google initiate the kind of offline activities it does here in other democracies?

- Is Google shutting out potential competition by obtaining a stranglehold on the internet?

Google’s policy, its CEO Eric Schmidt had once said, was to get right up to the creepy line, but not cross it. It has generated contentious debate about the firm’s activities and products, whether it’s accessing your e-mails to feed you targeted ads, something we have now come to accept grudgingly, or its soon-to-be-released Google Glass that comes fitted with miniature cameras and has advocates all worried about the next big breach on the privacy frontier.

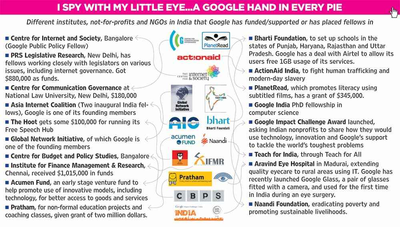

Not just online, where privacy violations and anti-competitive practices have raised concerns globally, some of Google’s offline activities in India too should have us asking questions based on conflict of interest and lack of transparency. Here too, the company seems to have placed itself right next to the creepy line. Especially the way it has gone about sponsoring research at key think-tanks and academia on areas that directly concern its business interests.

Nothing illustrates this better than the work of PRS Legislative Research, which Google has funded in the past. PRS produces policy briefings that are sent out to lawmakers and the media, including on internet governance. PRS hasn’t got a clearance to receive foreign funds since it became independent of the Centre for Policy Research in 2010, where it was launched, and has since then been largely funded by domestic sources.

|

|---|

|

Prashant Reddy, Blogger “That an Indian user seeking arbitration |

Does this growing network mean Google is having a say in shaping internet governance laws? Maybe yes. They should have a say by all means, just as other interested parties must get theirs. But given its influence and the certain opaqueness that marks its activities, some more transparency can only boost the credentials of a firm whose informal motto is—“Don’t be evil”. Google may have helped you find that bit of information from the googol tera bytes of online data but it has so far largely evaded discussion on how it has gone on to become big and influential in India. But while it may have been forced to back out from funding PRS directly, Google’s web of research fellows in this country is growing. In August this year, the Asia Internet Coalition, of which Google is a founding member, selected its two inaugural India fellows—Shehla Rashid Shora and Astik Sinha, both of whom will analyse policies concerning the internet environment here. Sinha also happens to be a social media advisor for BJP MP Anurag Thakur. |

So big that it hobnobs with Narendra Modi in the first of its Hangout series and, quite contrary to its espousal of free speech, has comfortable questions pitched to him. Or so influential that it has telecom minister Kapil Sibal, its bete noire from 2011 when his ministry was forcing them to pull down content, to attend the launch of chandnichowkonline.in, a business directory of Sibal’s constituency. Outlook made several attempts to get a reaction from Google but received none by the time this article had to go to the press.

|

|---|

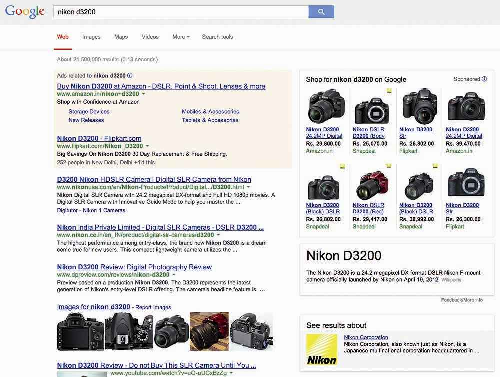

| Blurred lines Paid ads seem no different from search results for cameras |

Google, since 2011, has also placed three fellows so far under its annual Google Public Policy Fellowship programme at the Bangalore-based Centre for Internet and Society (CIS). The research is supposed to focus on “access to knowledge, openness in India, freedom of expression, privacy, and telecom”. Yet another crucial funding in May 2013 went to the Centre for Communication Governance at the National Law University in New Delhi, which does research on areas directly linked to its business interests. The agreement contains a clause that says “Google will not be excluded from any future business opportunities”. Its research director Chinmayi Arun did not respond to Outlook’s e-mail and said she was too busy to speak when Outlook called her up.

|

A third institution Google has funded is the media watch website The Hoot. After the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai when the government hastily amended the IT Act, clamping down in a restrictive spirit, noted journalist and the website’s editor Sevanti Ninan was one of the many criticising the government publicly in her articles. Google, she says, contacted her somewhere around mid-2009 seeking a proposal on how they could help with what she was working on. Ninan sent one proposing a Free Speech Hub and received a grant of $22,000 in January 2010 (approximately Rs 10 lakh at 2010 exchange rates) from Google to do so. The hub is an online forum to track free speech violation and highlight problems surrounding freedom of speech and expression and regulation of media. The commitment was renewed in February 2012 with another grant of Rs 42 lakh. Ninan says that while Google was “not interested in media ethics but free speech”, its approach was entirely “hands-off” to what the site could include on the hub. “I think it’s entirely up to the organisation being funded to decide how it handles a grant. At the same time, anything Google does should be under scrutiny just like other corporations.” |

“More transparency |

So just as it is necessary to publicise that Shell has ties with the India chapter of Brookings Institution or that Reliance sponsors the Observer Research Foundation, it is important that people know where Google is putting its money and for what gains. In fact, more so in the case of Google, a firm that touches our lives in so many more ways that Shell or Reliance does. Yet, a lot of what Google has been doing has gone without adequate publicity and scrutiny. Should we be any less sceptical of Google funding research that helps formulate policies on internet governance than we should be of, let’s say, the Tatas and Jindals on mining? “Google has huge money and its funding of research can be a very contentious issue, especially if it seeks to influence research. Therefore, parties who swear by full disclosure and transparency must adhere to it,” says senior journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta. “More transparency and accountability can only be good, both for Google and the organisations it funds,” adds Anja Kovacs, who works with the Internet Democracy Project.

|

|---|

| The great connector Hangout with Narendra Modi |

But there has been little of that transparency online. For instance, the Rules and Regulations Review of The Information Technology Rules, 2011, put out and sent to MPs by PRS Legislative Research has no mention that an interested party (Google) has funded its work. Similarly, The Hoot has no mention of Google funding it on the ‘About the Hub’ page even though it has details of Google’s funding on the ‘Support The Hoot’ page. Google has also funded numerous ngos, in areas such as health and education, and has sought to promote the use of technology (often theirs, such as in the ongoing Google Impact Challenge Award).

|

“Because there is |

This offline influence apart, Google’s hold online is worrying enough to call for action. The way it manipulates search results to favour clients of its AdSense programme is a global concern. For instance, a search for a popular phone model throws up matches of Google’s clients and features them more prominently than the actual site of the product. The Jaipur-based Consumer Unity and Trust Society (CUTS) conducted a survey that found most internet users could not tell an ad from an organic search result from Google. Says Madhav Dar, an independent anti-trust economist, “Given its financial clout and dominance of e-commerce, Google can directly deny traffic to downstream sites. And because the internet ecosystem is still in a formative stage here, this is something that requires intense and urgent scrutiny by the Competition Commission of India (CCI).” CUTS filed a formal complaint with the CCI in June last year alleging anti-competitive practices and abuse of its dominant position. BharatMatrimony.com too filed a complaint with the CCI in 2012 accusing it of directing online users’ search for “Bharat+Matrimony” to its rivals. |

For many, Google crossed the creepy line when it declared, in a court filing in August this year, that people sending e-mails to any of Google’s 425 million Gmail users need have no “reasonable expectation” that their communications are confidential. This is something that concerns Sunil Abraham, the executive director of CIS, which hosts Google fellows but has received no funding from the firm. “India has no omnibus horizontal statutes, neither sufficiently evolved vertical statutes in specific areas of telecommunication or the internet,” he says. “And because of that there is no office of the privacy commissioner in India and the absence of this regulator doesn’t tame the voracious appetite that Google has for personal information. This happens in other jurisdictions, but the Indian citizen is left vulnerable to Google when it comes to privacy.” “Part of Google’s practice can be absolutely abhorrent, such as the way in which it seeks to have a monopoly in digitising information and being the only one to organise it,” adds Kovacs.

|

|---|

| Amitabh Bachchan Google maps his home at WEF in Davos |

Another controversial move online has been the decision between Airtel and Google to allow the former’s subscribers free usage of Google’s service up to 1 GB. This has thrown up concerns of violation of “network neutrality”, a widely acknowledged concept that requires internet service providers to not discriminate against third party applications and service.

|

Journalist and blogger Shivam Vij, however, thinks concerns surrounding Google’s offline activities are misplaced. “As long as they keep coming out with transparency reports that show the majority of requests for user data and content removal are refused, I’d consider them an ally. One should be grateful that Google is funding to protect free speech and ashamed that Indian firms aren’t,” he says. “And if they really have been trying to influence MPs, they would have bribed them, not put out research.” Nikhil Pahwa, who runs Medianama, a digital media news and analysis website, is another person who says “he won’t look a gift horse in the mouth”. “I don’t know what the motives are, but I support what they are doing, especially given the way the state and Indian firms are failing us when it comes to protecting free speech online,” he adds. The only concern he has about Google is regarding its reported unwillingness to agree to a deal between the Advertising Agencies Association of India (AAAI) and the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI). The deal seeks to ensure smaller online publishers and advertising networks are paid on time by advertisers, who, in most cases, delay payments to smaller entities but always pay bigger players like Google on time. “Smaller players are suffering due to delay in payments, which can extend up to a year, a problem that Google does not face. The IAMAI initiative is something that Google is unwilling to support because it does not impact them,” he adds. |

"Anything that |

|  |

|---|---|

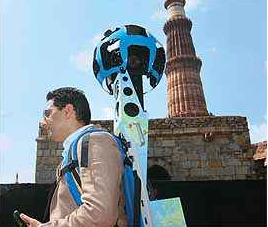

| The outreach Sibal attends the launch of chandnichowkonline, a business directory of his constituency; Qutub Minar, digitised | |

Criticising or questioning some of Google’s policies does not amount to siding with the government on cracking down on free speech on the internet. Outlook ran a cover in December 2011 where it was severely critical of the government’s attempt to muzzle online dissent. Neither does concern about Google’s activities stem from a fear of the foreign hand. Its expansion into Indian civil society has to be seen as an attempt by a profits-driven corporation to ensure its market interests in India are protected. The country becomes all the more important given the trouble it has been having in Brazil and in Europe, where the firm has been slapped with a slew of anti-trust charges. Keeping a close watch will only help enforce Google’s policy in India—not crossing the creepy line.