The Dangers Of Birdsong

Instant gratification? Social media can quickly turn the game into checkmate if you don’t keep your emotions in check.

Namrata Joshi's article was published in Outlook on January 25, 2014. Sunil Abraham is quoted.

“Woke up from a dream in which I had just learned that I was going to keep wickets for India. In my dream, I thought, let me share this news on Twitter. I didn’t, fearing I would be made a laughing stock.” These are few of a series of stream of consciousness tweets about a dream posted this Monday by author-academician Amitava Kumar. Tweets that don’t just have to do with dreaming of a personal achievement, but also about tweeting it. “Twitter has invaded even our sleeping life,” says Amitava on an e-mail but also admits that he didn’t think for a moment that he was sharing something private in a public place while tweeting his reverie. “Instead, perhaps, I was seeking a private connection with a lot of readers.” Which he did rustle up in good measure. He followed it up by tweeting a picture of his son with him, taken by his 10-year-old daughter Ila, as a homage to a similar photostream by author- photographer-art historian Teju Cole.

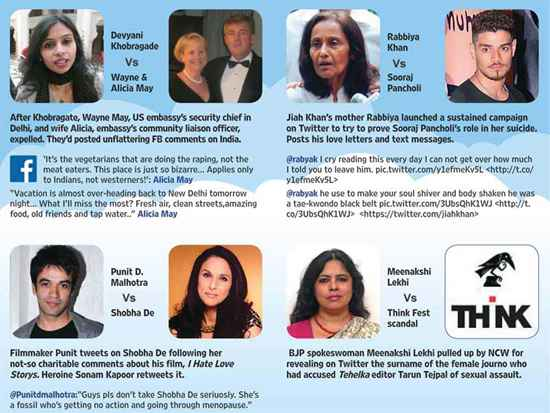

Amitava’s unfussy and creative candidness about tweeting things personal, which he prefers to see as “grappling with a form of writing” came in the wake of a weekend of vigorous debate on how social media platforms were bringing the private under unblinking public scrutiny—the immediate hook being the sudden, tragic death of Sunanda Pushkar after her no-holds-barred Twitter war with Pakistani journalist Mehr Tarar (over the latter’s alleged liaison with her husband Shashi Tharoor, which was consumed with much amusement by their vicarious, at times vicious, followers). The Tharoor incident is not a stand-alone case. Be it a confidentiality clause or diplomatic tact, a professional decision or personal affair or even a death of someone close to you, social media has become a stage to play out the classified and the confidential (see infographic) by the celebrities and the aam aadmi alike. The payback? Spats, comebacks, breakdowns, meltdowns, resignations, embarrassments, humiliations, kerfuffles....

And it’s not something confined to India alone. “US Congressman Anthony Weiner’s tweet of his, let’s call it, torso, to a young woman in Seattle is perhaps the most egregious example of a US politician behaving badly online,” says Amitava. No surprise then that Weiner became a butt of late-night comedy shows.

But the larger question here is why. Why this urge and urgency to share it all? What is it about a platform like Twitter or Facebook that makes people bare and dare? Is it that the immediacy, speed and reach allows them the easiest way to extend the boundaries of their secluded, lonely lives, get instant attention and fan the curiosity of someone out there who they don’t even know? And why is propriety and moderation getting thrown out of the window in the world of virtual exchanges? Adman-columnist Santosh Desai calls Twitter a “broadcast system to the universe”. The tweets are often “thought bubbles”, “something you mutter” without a full sense of what public means. “The spur of the moment opinion or feeling acquires public currency,” he says. “The unraveling of the human being, the opening up of the closed box then becomes a new source of stimulation and pleasure,” he says. “I sometimes wonder how we shared before Twitter. We talk about what we like, don’t like at the drop of a hat. At times you are vulnerable and vent things out without an agenda and without knowing the repercussions. We creative bunch are like that,” says popular actress Divya Dutta.

|

|---|

|

According to Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore, private information is a currency in the global attention economy. “One of the many ways of climbing the attention economy is to divulge private information. Those in public life like filmstars and socialites understand this completely and exploit all traditional broadcast channels and contemporary multicast channels like social media to amass public attention,” he says. Look closely and the online space is no different from the real. There are as many exceptions as there are rules. So for every exhibitionist handle that exploits our latent voyeurism, there is a Natasha Badhwar, one of the most life-affirming presences on Twitter. For her, like Amitava, sharing is a mode of expression. “Sharing gives us agency. We take back the power to tell our story, express our views, share our version in our own words,” she says. According to her, “honest” sharing fuels empathy. “It is contagious, it makes the reader want to share too,” she says. And from that sharing could emerge a new pool of acquaintances, friends and well-wishers. It may not be a virtual escape from the real but a journey and connect back to the actual, an expansion of the human circle than a depletion of it.

But not all our friends and followers need necessarily be sympathetic. Often they are also brutally savage. “The anonymity allows people to say exactly what they want without considering the implications. They don’t realise that it’s not just a handle but a human being they are talking to,” says Nikhil Pahwa, founder of medianama.com. Amitava compares it to drone warfare. “The technology of remote destruction has introduced a new experience of war, and a new logic of killing. You can kill with greater abandon; you can strike in unexpected places; you are confronted with few consequences of your fatal mistakes. Similarly, Twitter allows a mode of social exchange with less culpability. There are very few consequences for trolls, but disastrous ones for their victims,” he says.

But surely that doesn’t mean that you blur all the lines between the private and the public? How to exercise caution? How much to open up (or not) and how much of your core to keep to yourself? Life, after all, is too complex and fragile for blame games and finger-pointing at social media alone. It’s those using it who need to own up. “People need to take responsibility for what they say. It’s like someone telling me how he was abused for 15 minutes on the phone when he could have easily cut the call,” says Nikhil Pahwa. “It’s a modern form of communication which you have to embrace but there’s a line you must draw. For instance, my wife and I never interact on FB or Twitter. I keep the family to myself. Jokes are fine but I don’t abuse or use swear words,” says actor Ashwin Mushran. “There has to be a sense of decorum. I won’t put out what I gossip about with my friends. I have no strategy but am guarded by my own belief system,” says actor Rajat Kapoor.

“It’s normal human nature to express. Be it anger or frustration, as a counsellor I tell people to not suppress emotions but some moderation and etiquette need to apply in cyber space,” says Mukta Puntambekar deputy director of Pune-based Muktangan Rehabilitation Centre. “You have to accept that your followers and friends will have access to details about you. You have to exercise discretion in saving something of yourself for yourself. There are areas that need not be opened up for all,” says actor-comedian Vir Das, who recently posted an open letter on FB—‘Twitter Bad? Facebook Evil? or We Stupid?’—on the pointlessness of blaming social media for the Tharoor family tragedy. To extend the argument further, and add another layer to it, aren’t we also living in times when privacy itself is evolving, asks Rajesh Lalwani, CEO of blogworks and a self-confessed people-watcher. “My grandmother would not even eat in public. But we eat in restaurants, on the streets,” he says.

Privacy is also becoming an ambiguous, vague and complex entity. Getting tagged in a friend’s photo compromises your privacy without your involvement or participation. “The line between private and public has mostly dissolved because of the temporal persistence of digital traces in cyberspace, the global nature of the network and the ubiquitous and pervasive surveillance state,” says Abraham. “On Twitter and FB, things get circulated...what we put up, whether it’s a tweet, an update or a picture, is permanent unlike memory,” says Desai. The digital trail stays online. “We are leaving our digital footprints behind. What we post might be easy but the implications of it are complicated,” says writer, filmmaker and media observer Amit Khanna.

According to him, there is a gap between the progression of technology and society. “There are newer windows but our minds are not growing apace to handle the connected world in a mature way,” he says. So one needs to be additionally circumspect about what we do online, how much of us we put out there. The ‘creative minds’ don’t see it as cut and dried. Natasha thinks that sharing can make people vulnerable to ridicule. “Confronting and embracing that vulnerability is the only way forward. These are not real fears to cling to, these are fears to shed as we grow and realise the extent of our individual power.” Amitava says he has seen several careers destroyed because of a single tweet. But he’d hate to back down and be cautious. As he puts it, “You’ve got to push the envelope and experiment with expression. I hope that when my wrong moment comes, people will be forgiving.” Amen to that.