Is free speech an Indian value?

Is freedom of speech and expression deeply accepted in Indian society? Or is it merely a European cultural import that made its way along with the English language and appeared in the Constitution because of the founding fathers' genius? Satarupa Sen Bhattacharya reviews Freedom Song, a film and connects the dots.

Satarupa Sen Bhattacharya's blog post was published in India Together on April 27, 2013. Snehashish Ghosh is quoted.

Debates on freedom of speech can be traced back to the earliest evolutions of human society, but if there is a time which could be considered most apposite for this debate to come to the fore and dominate public thought and discourse, this surely would be it for Indian society.

From the banishment of literary icons such as Salman Rushdie to repeated assaults on artists and cartoonists seeking to express their viewpoints through their art, and even the gag on the common man’s voice in traditional and new media, freedom of speech and expression has found itself under fire increasingly and in the most alarming of ways.

Is India as a nation becoming more intolerant of contrarian perspectives, or is it merely that voices seeking to stifle dissent are now amplified, thanks to a greater number, as well as newer forms, of media covering this debate?

Can India really achieve free speech in the way that its founding fathers conceived of and constitutionalized it?

These are the questions probed in Freedom Song – a 52-minute documentary from the Public Services Broadcasting Trust, co-directed by veteran journalist, author and academic Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Professor Subi Chaturvedi.

Freedom Song, the film

Interestingly, since the time Freedom Song was conceived of and filmed, the clamp-down or attacks on free speech in India have only become more frequent and flagrant. This was made much before the time that Salman Rushdie, in almost a repeat of the 2010 Jaipur Lit-fest incident, was stopped by the state from attending the screening of Midnight’s Children in Kolkata; or when two young girls from Palghar in Maharashtra were arrested by the police merely because one of them had questioned on Facebook the derailment of normal life in Mumbai following Balasaheb Thackeray’s death and the other had ‘liked’ it; or even before the long-awaited Kamal Hassan film Vishwaroopam was banned for purportedly offending the sensibilities of a religious community in a few scenes, which the director eventually had to agree to censor in order to ensure that his creation could reach the audience.

Freedom Song, the documentary, chronologically precedes all of these as well as the debate and outrage over sociologist Ashish Nandy’s remarks on corruption and backward castes; yet, when one sees it now, recalls the numerous incidents highlighted in the film, and hears the debates that rage on, the larger context and culture that has facilitated the perpetuation of suppression become clearer. It also drives home, disturbingly, the alarming regularity with which speech and expression have been muffled. It can thus be seen as a commentary on the gradual but consistent build-up to the current climate where there is an almost systematic and continuous crackdown on free speech whenever it inconveniences the powers-that-be.

Gags on expression - recent incidents

In July 2010, when T.J. Joseph, a professor of Malayalam at the Newman College in Thodupuzha (Ernakulam district) in Kerala was arrested by police following a controversial examination question set by him, allegedly containing disparaging remarks about the Prophet Mohammad. He was released on bail but suspended from his post following protests by Islamic organizations. But suspension wasn’t the last of Joseph’s tribulations: he was brutally attacked by a gang of men who chopped off his hand at the wrist with an axe. He was also stabbed in the arms and legs. While Joseph’s hand was stitched back in a 16-hour-long operation, even as he was recuperating, his college terminated his services on grounds that he had offended the religious sentiments of students. He was also stripped of all benefits and pension.

Curiously, Joseph himself distances the entire incident from the issue of freedom of expression. In his conversation with the film-makers he says that whatever happened could be interpreted as attempts to meddle with and dilute academic independence in the state. “The incident is not related to the issue of freedom of expression...external attempts to break down communication between students and their teacher was at the core of the entire episode,” says Joseph. Even Union Minister for Human Resource Development Shashi Tharoor, who hails from the state himself, attributes this incident to the act of some anti-social fringe elements who masquerade as representatives of a particular community. But these arguments from the victim himself, and an eminent authority, cannot resolve the question of his expulsion from service. Nor can they address the fact that the atmosphere of tolerance in the country is such that anti-socials can hijack as simple an academic exercise as question-setting to their advantage and perpetrate such atrocities.

A more recent incident highlighted in the documentary is the arrest and detention of Ambikesh Mahapatra, a professor of Chemistry in Jadavpur University of West Bengal for forwarding a set of cartoons that allegedly defamed Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. Shortly after the dismissal of Union Railway Minister, Trinamool’s Dinesh Trivedi, and his replacement by Mukul Roy, the widely-circulated cartoon showed Roy and the CM having a conversation along the lines of one in a very popular Satyajit-Ray film, conspiring to get rid of Trivedi.

Ambikesh was not the creator of this cartoon – as he himself says, he received it on a forwarded email. Amused by it, he wanted to share it with his friends. Thus he forwarded it again to over 60 members of his housing co-operative society, some of whom happened to have affiliations to the party in power. This action led to the professor being arrested and charged under IPC Sections 509 (insulting the modesty of a woman), Section 500 (defamation) and Section 66 A of the IT Act (causing offence using a computer). He had to spend a night in jail before he was released on bail the following afternoon.

However, charges against the professor have since been dropped and the West Bengal Human Rights Commission (WBHRC) ruled that the state police were indeed guilty of harassing the professor (and one of his colleagues, who had also been arrested).

|

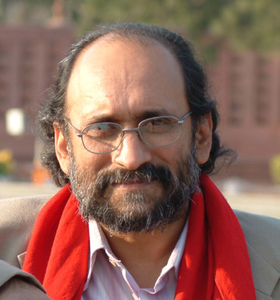

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, co-director of Freedom Song

|

Muffling creativity One thing that stands out pretty sharply in Freedom Song is the deep angst shared by the creative fraternity in the country over the assault on free speech. Perhaps, by dint of being that section of society which is most inclined to spontaneous and non-conformist expression, they also constitute one of the most vulnerable groups when it comes to being restrained or gagged.

|

Often, the gag on works by artists and writers has transcended to direct discrimination against the person himself. The state of West Bengal banned exiled Bangladeshi author Taslima Nasreen’s book “Dwikhandito” in 2003 on fears that it would stoke communal disharmony. When human rights activists challenged the decision in Court and managed to win rulings on her behalf, the writer herself was banished from public life in the state. She was unceremoniously asked to leave the state in 2007, after violent protests against her by fundamentalists. Much later in 2012, even after the political reins in the state had changed hands, the launch of her book at the Kolkata Book Fair was cancelled upon threats of protest.

One of the most heart-rending is the story of Pakistani singer Ali Haidar, who confesses to being almost brainwashed, in one of his weakest moments, by radical elements into believing that the loss of his child was in fact a retribution for him having taken up music as a profession.

The feeling of anger, frustration and even a sense of bewilderment among the artists, writers and performers interviewed in the documentary is almost palpable. As Rajiv Lochan, Director of the National Gallery of Modern Art, says, “Freedom of expression, creative freedom…in simple words, that is the only freedom you are born with...” The unuttered question of how anyone can take that away from you hangs heavy in the silence.

If artists are the most vulnerable, they are also perhaps the most resilient. In the context of the various cartoon controversies that this nation has seen and the proscriptions of cartoonists from Shankar to Aseem Trivedi, eminent political cartoonist Sudhir Tailang says, “We cartoonists know only one way of protest, which is the most peaceful, Gandhian way…you do what you want, we’ll draw a cartoon…and more cartoons… we’ll flood you with cartoons.”

The defiance and rejection of censorship is also strongly voiced by noted danseuse Mallika Sarabhai, who talks of the various forms of attack and insult that she has been subjected to for her unconventional presentations and activism, but asserts that despite all of it, she feels it is her “dharma to go on.”

The language barrier

Perhaps unwittingly, Freedom Song tends to favour the premise that freedom of speech as a principle in India is largely a preoccupation among the English-educated, intellectual and creative segments of the populace. Even the musical score that has played such a dominant part in invoking the spirit of freedom throughout the film seems to underline that - from the refrains of Bob Marley’s ‘Won't you help to sing these songs of freedom,’ to the remixed pop version of ‘Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram’ that one hears in parties and joints in India’s westernized urban landscape.

How attuned to the issue of free speech is the wide majority of India, the section that still follows vernacular media and are relatively distanced from the constructs of Anglo-Saxon influence? The verdict on the linguistic divide does not emerge with clear certainty when we talk to intellectuals or thought leaders from various parts of the country. In the words of academic Subhoranjan Dasgupta, a professor at the Kolkata-based Institute of Development Studies, mainstream Bengali media has played a big role in highlighting transgressions of freedom of speech and expression every time it has occurred, irrespective of the political regime in power at the time. "Whether in the case of the ban on Taslima Nasreen or the arrest of Professor Mahapatra, local media - and especially two widely-followed dailies, the Anandabazar Patrika and Ei Shomoy - have been audibly vocal and consistent in their coverage of these incidents," says Dasgupta. "Irrespective of political ideologies, the common man in Bengal knows that Taslima Nasreen got a raw deal or that what happened to the professor was not acceptable," he adds. Ostensibly, the role of local media in such public consciousness cannot be written off. In a way, it might not be an exaggeration to say that the voices of these publications have been instrumental, to a large extent, in ensuring that these issues grab the eyeballs of the largest number possible, and hence gain traction. And yet, a completely different picture emerges as one reaches out to another part of the country. Badri Seshadri, Publisher, New Horizon Media - a Chennai-based company that publishes books in Tamil, and an active blogger, feels that notions of freedom, or free speech, are essentially offshoots of the modern era which have found a voice in our country primarily through English media. Seshadri goes back to the freedom struggle in India when many among the noted thought leaders and freedom exponents wrote both in English and the local language. In those days, the discourse on freedom of thought and expression were perhaps more at par across spheres. But with the dying trend of bilingual writing, intellectual writing increasingly gravitated towards English. Today, the gulf between English writers and regional writers has become so huge in his state that even the most fundamental of issues are discussed in vocabularies that cannot bridge the schism. Issues pertaining to secularism and democracy are viewed with a completely different lens in vernacular media, and those pertaining to liberalism, not at all. "Take the case of the most recent ban on Kamal Hassan's Vishwaroopam," points out Seshadri; "this was not a film made in Hindi or English that you could assume to be emotively disconnected from the Tamil mindspace. It was a film that had been made by one of the cult film personalities of the region, and yet even as the national English media followed this issue and consistently questioned the violation of an individual's right to creative freedom, deliberations in local channels and publications were strangely muted and focused only on whether or not the disputed scenes in the film could be considered to be offensive to the Islamic community. The larger debate on whether one has the right to offend, in an impersonal way, was completely missing." Those who want to toe the line of liberalism either through their writing or new media are dismissed as harbouring "fancy" ideals or pandering to Western sensibilities. Guhathakurta, himself, disagrees with the claim that free expression is essentially a Western construct or that debates around it are restricted to the chattering classes in plush drawing rooms. “It is something that concerns every common man,” he says, referring to the case of Laxmi Oraon, the teenaged tribal girl who was stripped, beaten and molested in the streets of Guwahati, where she had been part of a peaceful protest rally, seeking the inclusion of 80 lakh Adivasis living in Assam in the ST category. Traumatised and deeply angered by the brutal injustice meted out to her and the lack of legal redress, Laxmi eventually even contested the Lok Sabha elections, points out the director in order to elucidate the struggle that even the most marginalized take part in to press for their fundamental rights.

|

|---|

| A still from the documentary Freedom Song. Pic: PSBT India via Youtube |

"Reasonable” restrictions

Despite the continuous infringements on artistic and even individual expression, what emerges from the film is not a blanket wave of intolerance that is engulfing society but rather certain powerful groups with vested interests who are driven either by fanaticism for their ideologies or by the lure of political mileage to raise voices against freedom. In the age of 24x7 channels, their voices gain in both volume and pitch and new media enables greater visibility and debate around it.

As Tharoor says, “The government has the lowest level of tolerance possible because it cannot be seen as offending anybody who is held precious by any segments of Indian society.”

Veteran journalist Saeed Naqvi points out, “You have a whole link between the politician, the vote bank and the proprietor. Therefore, the freedom of the press, while this trio exists, is under threat.”

But having said all of the above, it is also clear that defining freedom, especially in an absolute sense, is in itself a huge challenge that most of society acknowledges. More so, in the context of Article 19 (2) of the Constitution which itself allows the state to impose “reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right...in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.”

Senior journalists such as Rajdeep Sardesai are quoted in the documentary, expressing their support for such ‘reasonable restrictions’ to combat the spread of expression or opinion that fuels divisiveness or hatred in society. But the fact remains that such restrictions not only add a qualifier to freedom as enshrined in the founding principles, but also create the larger question of ‘who decides?’

Young India however would prefer to see Article 19 (2) as an enabler rather than as a veto. As Apar Gupta, an advocate of the Supreme Court says in the film, he would like to believe that the incorporation of “reasonable restrictions” was done with a view to ensuring that the Constitution does not remain a static document and does not apply only to fixed definitions of facts and circumstances. Certainly not with the objective of curbing any form of dissent or deviation from convention.

Fali S. Nariman, senior advocate to the Supreme Court and a constitutional jurist, also points out very pertinently that the range of restrictions in 19(2) does not include public interest.

Reality does not bear that out though; especially when one looks at the many recent instances of arbitrary impositions of Sec 66A of the IT Act in booking individuals for expression of their opinion and stances through channels offered by new media and Internet. The documentary in itself does not delve deep into the challenges and threats to freedom of expression that have emerged in the FB/Twitter era, perhaps because many of the most volatile and controversial cases surrounding freedom of speech on the Internet occurred after the film was made. But a new debate is brewing in India, especially after the Palghar incident or the arrest of a Puducherry businessman for allegedly posting 'offensive' text on the micro-blogging site Twitter about the son of an Union Minister.

Snehashish Ghosh, a lawyer and Policy Associate at the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore, says, “Essentially, there are eight restrictions on freedom of speech and expression as enumerated in Article 19(2) of the Constitution. The Supreme Court in many cases has held that these reasonable restrictions should be construed narrowly and with due regards to the value of freedom of speech in a democratic society. Section 66A in its current form goes well beyond the restrictions laid down under Article 19(2). Therefore, it is liable to be struck down for being in violation of Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution.”

Snehashish also feels that technologically, in the present time, it would be near-impossible to 'monitor' the Internet. As far as regulations are concerned, there are laws already in place which ensure the implementation of reasonable restrictions. For example, the Indian Penal Code, 1860 already covers offenses such as incitement of violence, obscenity, criminal intimidation and outraging religious sentiments. The laws which are being applied offline are well equipped to deal with offenses committed online. There is no need to have extraordinary laws where ordinary laws suffice.

But in a country that appears to grow increasingly thin-skinned with time, the import of such logic could well be lost.

Access and freedom

Interestingly, Freedom Song begins with a series of frames capturing the widely different and divergent faces of Indian society, fast moving scenes juxtaposing the educated, affluent sections of urban India against the child who performs on sidewalks to earn his bread or the old emaciated man getting his night’s sleep on the pavement. The clear correlation between access – to basic needs, education and media – and the very consciousness of freedom is hard to ignore.

“Freedom to me is the ability to do what I want, where no one tells me to do anything” says one child on screen, evidently from an English-speaking, relatively privileged background; but one cannot help feeling that his coherence and articulation on freedom would be hard to come across in the children on the streets who are filmed in some of the previous shots.

The point that access to the very basic necessities of life is a necessary condition for freedom of expression is driven home by social activist Ram Bhat in the documentary, who says that despite the technologies aiding free expression, and the profusion of players in this debate, talk of freedom of speech will be pointless unless the problem of access is solved. In its absence, such freedom will remain the privilege of a few.

On balance, in all the voices that emerge from our conversations, and the many more episodes that Freedom Song, the documentary narrates, the only thing that can be concluded without doubt is the challenge of establishing freedom as a perennial or permanent concept in a country as complex and diverse as India. A truly effective and desirable state of free speech and expression can only evolve out of a continuous, fearless, rational dialogue between society and its stakeholders, in which all voices are expressed and heard.

Whether India, as a whole, can facilitate such a dialogue is going to be the moot question in the times to come.