Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions: Mapping the Stakeholders' Response

The procedure and tests surrounding software patenting in India have remained ambiguous since the Parliament introduced the term “per se” through the Patent (Amendment) Act, 2002. In 2013, the Indian Patent Office released Draft Guidelines for the Examination of Computer Related Inventions, in an effort to clarify some of the ambiguity. Through this post, CIS intern, Shashank Singh, analyses the various responses by the stakeholders to these Guidelines and highlights the various issues put forth in the responses.

I. Introduction

In June, 2013 the Office of Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks ('IPO'), released the Draft Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions ('Guidelines'). The aim of the Guidelines was to provide some much needed clarity around patentability of Computer Related Inventions ('CRI'). The Guidelines discuss the procedure to be adopted by the examiners while examining CRI patent applications. In response to the Guidelines, several stakeholders submitted their comments to either accept, reject or modify the interpretation provided by the IPO. Most of the comments circled around the phraseology of Section 3(k), Patents Act, 1970 ('Act'). In its current form, Section 3(k) reads as "a mathematical or business method or a computer programme per se or algorithms", and comes under Chapter III of the Act which lists inventions that are not patentable. Simply put, this means that software cannot be patented in India, unless it is embedded/combined in with some hardware. While this is the most widely accepted interpretation of this Section 3(k), there have been contradictory interpretations as well.

In this note, I shall look at the various ambiguities surrounding patent application for CRIs. The note has been divided into five parts. Part II briefly reiterates the legislative history behind Section 3(k) and CRI patenting. Part III would briefly summarize the various parts of the Guidelines where the IPO has given their interpretation and opinion on the various issues surrounding CRI patenting. Part IV would then map the position of the stakeholders on each ambiguous point. Lastly, Part V would give the conclusion.

II. Legislative History

Under the Patent Act, 1970, prior to the 2002 Amendment, there was no specific provision under which software could be patented. Nonetheless, there was no explicit embargo on software patenting either. For an invention to be patentable, under Section 2(1) (j) of the Act, which defines an invention, general criteria of novelty, non-obviousness and usefulness must be applied. Software is generally in the form of a mathematical formula or algorithm, both of which are not patentable under the Act as they do not produce anything tangible. However, if combined or embedded in a machine or a computer, the resultant product can be patented as it would pass the aforementioned criteria.

The Parliament, in 1999, sought to amend the Act to bring it in conformity with the changing technological landscape. Consequently, the Patent (Second Amendment) Bill, 1999 was introduced in the Parliament which was then referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee ('JPC'). The ensuing Bill proposed Section 3(k) in its current phraseology. It reasoned that:

" In the new proposed clause (k) the words ''per se" have been inserted. This change has been proposed because sometimes the computer programme may include certain other things, ancillary thereto or developed thereon. The intention here is not to reject them for grant of patent if they are inventions. However, the computer programmes as such are not intended to be granted patent. This amendment has been proposed to clarify the purpose. "

The Bill was then enacted as the Patent (Amendment) Act, 2002 and reads in its current form as:

Section 3(k) - "a mathematical or business method or a computer programme per se or algorithm"

This created some ambiguity with respect to the interpretation of the term "per se". It was interpreted to mean that software cannot be patented unless it is combined with some hardware. This combination would then have to comply with all the tests of patentability under the Act.

In December, 2004 the Patent (Amendment) Ordinance, 2004 ('Ordinance') was enacted which amended Section 3(k) to divide it into two parts, namely Section 3(k) and Section 3(ka).

"(k) a computer programme per se other than its technical application to industry or a combination with hardware;

(ka) a mathematical method or a business method or algorithms; ".

In February, 2005 the Ordinance was introduced in the Parliament as the Patent (Amendment) Bill, 2005.This included the amendment to Section 3(k) as under the Ordinance. In the Objects and Reasons it clarified that the intention behind the amendment was to " modify and clarify the provisions relating to patenting of software related inventions when they have technical application to industry or in combination with hardware ". However, the final amending Act did not divide Section 3(k) as proposed by the Ordinance. In the press note, by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry it was noted that:

"It is proposed to omit the clarification relating to patenting of software related inventions introduced by the Ordinance as Section 3(k) and 3 (ka). The clarification was objected to on the ground that this may give rise to monopoly of multinationals."

Later, in the same year the IPO release a Manual of Patent Office Practice and Procedure, 2005. Here, it noted that "a computer readable storage medium having a program recorded thereon…irrespective of the medium of its storage are not patentable". This did nothing to clarify the ambiguity that existed.

Similarly, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce, 88th Report on the Patent and Trademark System in India (2008) noted the uncertainty surrounding the term 'per se' and said that there was a need to clarify the same. It did not do anything in furtherance of pointing this out.

The 2011 Manual of Patent Office and Procedure, 2011 tried to elaborately deal with the ambiguity. Nonetheless, substantively it did not change the uncertainty. It stated that:

"If the claimed subject matter in a patent application is only a computer programme, it is considered as a computer programme per se and hence not patentable. Claims directed at computer programme products' are computer programmes per se stored in a computer readable medium and as such are not allowable. Even if the claims, inter alia, contain a subject matter which is not a computer programme, it is examined whether such subject matter is sufficiently disclosed in the specification and forms an essential part of the invention."

III. Draft Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions, 2013

The Draft Guidelines were released on June 28, 2013, following which stakeholders were invited to give comments.

Terms/ Definitions used while dealing with CRIs

At the outset, the IPO put a caveat to say that the Guidelines do not constitute 'rule making'. Consequently, in case of a conflict between the Guidelines and the Act, the Act shall prevail. After the Introduction and Background, in Part I and Part II respectively, the Guidelines looked at the various definitions/terms that correspond to CRI patent claims in Part III. In all, there were 21 such definitions/terms that were sought to be clarified. These definitions can be branched into three categories.

Category I- Where the definition/term was borrowed from some other Indian stature.

Category II- Where the definition/term was construed according to the plain dictionary meaning. Category III- Where the Guidelines tried to give their interpretation to the term/definition.

Under Category I, there were seven definitions whose meaning was derived from some other stature. The meaning of Computer Network, Computer System, Data, Information and Function were derived from Information Technology Act, 2000 ('IT Act'). The definition of Computer Programme was taken from Copyright Act, 1957. Lastly, the definition of Computer was taken from both Copyright Act and IT Act.

Under Category II, the Guidelines underscored five definitions whose meaning was to be borrowed from the Oxford Dictionary. These were algorithm, software, per se, firm ware and hardware. Importantly, it was noted that these definitions have not been defined anywhere in Indian legislations. Lastly, under Category III the Guidelines tried to interpret certain terms according to their understanding. These terms included, Embedded Systems, Technical Effects, Technical Advancement, Mathematical Methods, Business Methods etc.

Categorization of CRI claims

In Part IV, the Guidelines tried to broadly group the various CRI patent applications under four heads. These categorizations tried to give an insight into what the patent examiners look for while rejecting a patent application.

- Method/process:

Without defining what a method or process would entail, the Guidelines stated that any claim carrying a preamble with "method/process for..." shall not be patentable. It clarified that claims relating to mathematical methods, business methods, computer programme per se, algorithm or mental act are cannot be patented as they are prime illustrations of claims under this category. Further, the Guidelines gave specific examples of each of the aforementioned claims.

- Apparatus/system

The second category consisted of claims whose preamble stated that the patent application was for an "apparatus/system". Under this, the patent application must not only comply with the standard tests of patentability- novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability, but also define the inventive constructional or hardware feature of the CRI. However, in contradictory statements, the Guidelines try to narrow down the prerequisites for a claim under this category, only to state that such claims cannot be patented.

- Computer readable medium

While stating this as a category, the Guidelines do not elaborate on what this exactly means and what types of claims would be rejected being under this category.

- Computer program product

This category includes computer programs that are expressed on a computer readable medium (CD, DVD, Signal etc.). Further, infusing ambiguity to the debate, the Guidelines failed to differentiate between Computer Readable Medium and Computer Program Product.

Examination Procedure used by IPO

The examination procedure for CRI patent application in the Guidelines is similar to other patent applications which look at novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. However, claims relating to determination of specific subject matter under the excluded categories (Method/Process, Computer Readable Medium, Apparatus/system, and Computer Program Product) require specific examination skills from the examiner.

Under the excluded category itself, Method/Process requires subjective judgement by the examiner as to whether such a claim qualifies to be classified under this category or not. For investigating the inventive step involved in the 'method/process', the technical advancement over existing knowledge in the technological field has to be analyzed. Any patent claim from a non-technological field shall not be considered.

The Guidelines then tried to clarify the controversial Section 3(k) which eliminates the patenting of computer programmes per se. While previously stating that the definition of the term 'per se' as borrowed from the Oxford dictionary meant 'by itself', the Guidelines stated that computer programme loaded on a general purpose computer or related device cannot be patented. Nonetheless, while filing patent application for a novel hardware, with a loaded computer programme, the likelihood patenting the combination cannot be ruled out. Further, the stated hardware must be something more than a general purpose machine. Essentially, a patent for a novel computer programme combined with a novel hardware, which must be more than a general purpose machine, may be considered for patenting. It then gave several examples which were followed by flowcharts to further clarify ambiguities surrounding CRI patentability. Interestingly, all these examples and flowcharts only listed the inventions that are not patentable.

IV. Response by Stakeholders

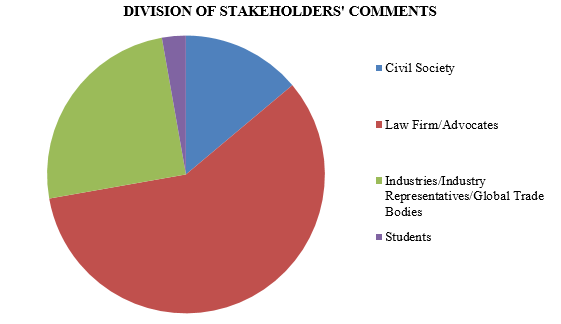

Many and various comments were received from 36 stakeholders that including lawyers, civil society members, law firms, students, global and national trade bodies and industry representatives.

Our compilation (and the first level of analysis) of the Stakeholders' Responses is available here.

|

|---|

While all the stakeholders' applauded the much needed transparency in the IPO, substantively they differed considerably on various issues and highlighted some inconsistencies. In this part, I shall map the responses of the various stakeholders'. While doing so, I shall also try and find specific patterns to the responses corresponding to the following segments:

1. Civil Society

2. Law Firm/Advocates ('law Firms')

3. Industry/ Industry Representatives/Global Trade Body (Industry)

4. Students

These segments have been created on the assumption that each of the aforementioned segment would lobby for similar kind of policy.

Interpretation of Section 3(k)

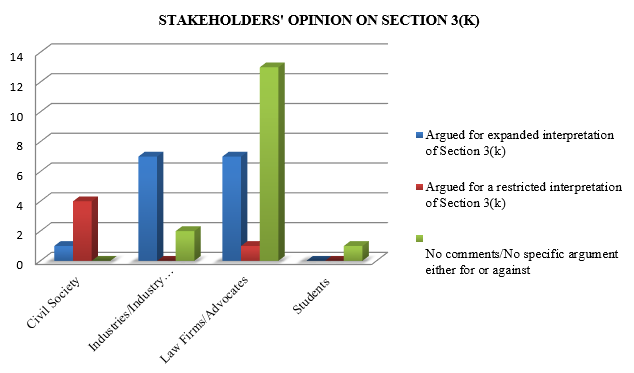

One of the major points of deviation between the stakeholders was regarding the interpretation of Section 3(k) which encapsulates the term "computer programme per se".

The industry responded by critiquing the current CRI patenting regime in India as being "restrictive" ( FICCI , NASSCOM, US India Business Council and Bosch ). While some industry representatives sought clarifications due to uncertain phraseology, there was no industry representative that favored restricted interpretation to exclude software patenting altogether. While opposing the Guidelines, they sought assistance from the legislative history behind introduction of Section 3(k). It was pointed out that the term 'per se' was included to raise the threshold of patentability to something higher than the previous patentability standard, but it did not explicitly exclude patent protection for software.

The general perception of the stakeholders, keeping in mind the current Guidelines, was that for patenting software it had to be combined with some hardware. This combination would then be scrutinized against the triple test of novelty, inventive step and industrial application.

While the Guidelines noted that the hardware involved must not be general purpose hardware and that the chances of software patentability would increase significantly if novelty resides in the hardware; however, most of the industry and global trade bodies disagreed with this interpretation. They argued that if software in combination of hardware technically advances the existing technology, then such an innovation must be patentable, despite being combined with a general purpose machine (Bosch). Another explanation supporting expanded interpretation was that much of the technological innovation is accomplished through software development as compared to hardware innovation and novel software can achieve technical effect without the hardware developments ( BSA- The Software Alliance ). Consequently, software development that allows a general purpose machine to perform tasks that were once performed by a special machine must be incentivized. Some stakeholders interpreted the Guidelines to reason that hardware must be completely disregarded while examining patentability of software (Majumdar & Co. ).

Most of the responses from the civil society argued for a restricted interpretation of Section 3(k) ( Centre for Internet & Society). They concurred with the interpretation provided by the IPO to exclude software patentability. Most of the stakeholders responded seeking further clarification on the subject (Software Freedom Law Centre, K&S Partners and Xellect IP Solutions).

|

|---|

However, within each segments itself there was difference of opinion on the interpretation of Section 3(k). For instance, out of the five civil society members, four wanted to restrictive interpretation while one of them favoured expansive interpretation to include software patenting. Similarly, 13 law firms sought further clarification on the subject matter, while seven argued for expansive interpretation and one of them argued for restricted interpretation. The most consistent response was from the industry that clearly favoured software patenting and called the Guidelines "restrictive". Seven out of the nine industry representatives supported expansive interpretation and the other two sought further clarifications on the subject.

Section 5.4.6- Hardware

The interpretation of Section 3(k) until the release of the Guidelines was that software in combination with some hardware could be considered for patenting. However, the Guidelines increased the threshold stating that this hardware must be "something more than a general purpose machine". A stakeholder pointed out that increasing this threshold would go against the legislative intent as the requirement of a novel hardware has not been mentioned anywhere in the Act ( Anand & Anand ).

The industry's perspective on this matter was largely uniform. They pointed out the large technological field that would be eliminated from the scope of patentability if the interpretation provided by the Guidelines is adopted ( Bosch). Also, the investigation of novelty in the hardware would disincentives inventors in the field of CRIs ( Kan & Krishme ). Most of the stakeholders, across segments, sought more clarification on the role of hardware under Section 3(k) (Majumdar & Co. Centre for Internet & Society).

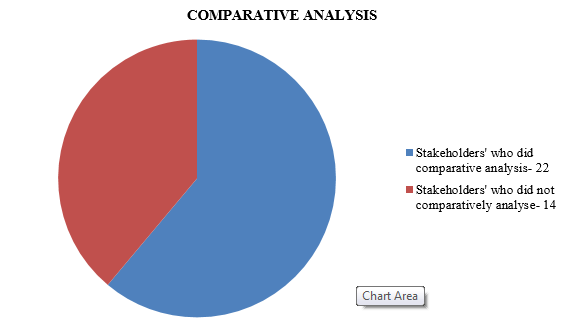

Comparative Analysis

Much of the criticism surrounding CRI patenting policy in India is based on the comparative inconsistency with similar laws in other jurisdictions. Comparative analysis on the subject has only been provided by the stakeholders that support software patentability. They point out that most countries like US, UK, Japan and the European Patent Convention allow patenting of software, and India must also do the same in order to comply with its international obligations under the TRIPs Agreement. Paradoxically, stakeholders who supported the current practice chose not to comparatively analyze CRI policy of other jurisdictions. While most of the stakeholders simply jumped to analyze comparative jurisprudence on the subject, only one of them gave a reasonable explanation for such a comparison ( LKS). It was noted that the Supreme Court of India and the Intellectual Property Appellate Board regularly borrow from foreign decisions to either accept or deny patents. Therefore, while formulating any policy on the matter, the position in other jurisdictions must be considered.

It was reasoned that the term 'per se' used in the Act, is similar to the European Patent Convention and UK Patent Act, 1977 where the term 'as such' has been used. Therefore, while juxtaposing both the terms, the interpretation of 'per se' must be similar to 'as such'. Consequently, software patenting must be allowed subject to the tests evolved by the courts. Similarly, the term 'as such' has been used by several Asian countries including China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. In these countries, software in concert with a specific hardware that resolves a technical problem thereby achieving a technical result can be patented ( Krishna and Saurastri Associates ).

Likewise, while comparing the jurisprudence of US, the landmark case Diamond vs. Diehr, which marked the beginning of software patenting was cited ( Subhojeet Ghosh and US India Business Council ). Several others argued that India must align their laws with global standards ( Bosch, Phillips Intellectual Property and Standards , Sun Smart IP Services , United Overseas Patent Firm).

|

|---|

Business Method

The Guidelines tried to narrow down the definition of 'Business Method' to clarify that such claims cannot be patented. It was urged that the Guidelines reconsider such a blanket embargo ( Legasis Partners- Advocates and Solicitors, Anand & Anand ). While judging patentability, a patent must not be rejected simply because it mentions business method or business method related terminology. What must be examined is whether the inventive step resides in the technical or non-technical part of the claim ( Legasis Partners- Advocates and Solicitors). A distinction must be made differentiating as to what software implementing business method and a software relating to the technical aspect of the transaction ( Anand & Anand ). While the former can be rejected, the latter must be accepted subject to the triple test of patenting.

It was pointed out that reevaluating a business method claim apart from a method involving financial transaction; monopoly claim over trade and new business strategies; monopoly claim over new types of carrying out business and method of increasing revenue; must be rejected (Law Offices of Mohan Associates , Remfry and Sagar, FICCI ). The more overarching opinion of the stakeholders was there is no objection to the exclusion of business method patents, but what constitutes business methods need more clarity (D. Moses Jeyakaran, Law Firm of Naren Thappeta , Japan Intellectual Property Association ).

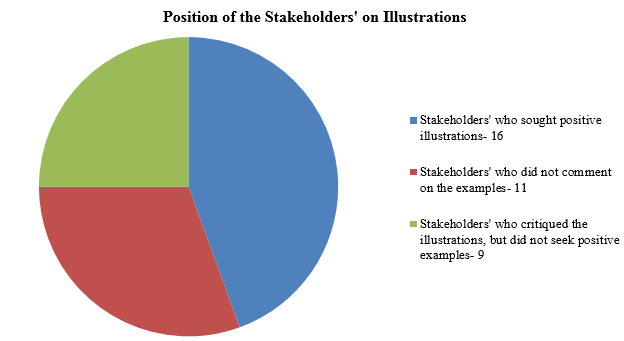

Critique of Examples and Flowcharts

The Guidelines provided for several examples and flowcharts to foster a better understanding of the subject matter. However, a notable feature of each of these was that they only gave examples of what claims would be rejected. This was sufficiently pointed out by most of the stakeholders who sought more positive examples (Bosch, BSA- The Software Alliance , K&S Partners , FICCI , Xellect IP Solutions, Japan Intellectual Property Association , In-House Intellectual Property Professional Forum, NASSCOM , Obhan & Associates , Remfry & Sagar, Tata Consultancy Services ). It was pointed out that the examples have not sufficiently elaborated on their relation with Section 3(k) ( FICCI ), and some of them are "weak, obscure and incorrect" ( Software Freedom Law Centre). These examples also fail to elaborate on the tests that have previously been applied by the Patent Office ( LKS). Overall, the general perception was that, the examples were confusing and greater clarity along with positive examples was needed ( LKS, Anand & Anand ).

|

|---|

Interestingly, out of the 25 stakeholders' who commented on the illustrations, 16 sought positive examples. Further, most of the positive examples were sought by industry representatives and law firms who supported software patenting.

V. Conclusion

It has been over a year since IPO released the CRI Guidelines. On release, it invited suggestions in order to revise the Guidelines, but the revised version has still not been released by the IPO. The Guidelines were authored from a patent examiner's perspective; however, while doing so it obscured the matter further. It was argued that in totality the application of the Guidelines would now make the patentability of software stricter. It was also pointed out that the Guidelines have not taken into account the legislative history and the specific rejection of the Ordinance in the 2005 Amendment.

The responses received by IPO gave conflicting opinion on the same issue. In general, it can be concluded that the industry and law firms were in favour of allowing software patenting. They sought removal of the hardware requirement for software patentability. Most of the stakeholder's who favoured software patenting also undertook a comparative study of jurisdictions like US, UK, EU and Japan to point out the difference in the software patenting policy. Further, they also wanted the Guidelines to give positive examples wherein CRIs patenting has previously been allowed.

Admittedly, the Guidelines have no legal standing and much like the Patent Manual, they serve merely to guide the patent applicants and provide transparency patent examination. Overall, the Guidelines failed to explain the previous inconsistencies surrounding the subject matter. In conclusion the Guidelines mention that it would periodically release and update the Guidelines incorporating the stakeholder's comments. Considering the diverse set of opinions received by the IPO, it now needs to be seen which suggestions are accepted until the next round of comments.