The Unsocial Network

Has social media become a threat to democratic states even as it serves as a vehicle against totalitarian regimes? Its abuse during the London riots has reopened the question.

Power of the the people is a double- edged sword. Power to the people is positively divisive. Especially, when the people become a mass, masked mob on the internet, using the power of proliferation of social networking sites to support, express – and, sometimes, incite. As was evident in the recent Tottenham riots, which have cast a shadow over BlackBerry Messenger and Twitter because of the way they have been used by ‘goons in the hood’ to beat the police. While BlackBerry messages appealed people to arm themselves with hammers to loot stores and bring cars along to carry the stolen goods, many tweets were posted to unite rioters.

Have social networks become a Frankenstein’s monster, which is being abused by anti-social elements for their nefarious ends? Media reports in London said that eight people in Cheshire had been arrested as suspects for encouraging rioting via the social media. Can social networks become a real threat to democratic states, even as they serve as vehicles for revolutions against totalitarian regimes? Should they be subjected to state scrutiny? “If social media shows a negative tendency, as was evident with the riots spreading to other parts of England, then it is symptomatic of an actual problem on the ground. A problem which has not been addressed by the state. The solution lies in solving that problem, social media is only an indicator,” says Anivar Aravind, IT consultant and commentator.

When it comes to social networking media, people’s messages are conveyed without censorship – as opposed to being edited before being delivered to the public in conventional media such as newspapers, magazines and even television, Aravind points out. Which is why social networking should be treated no differently than any other form of communication, says Jonathan Crossfield, social media expert and community manager at Ninefold, a cloud platform provider in Australia.

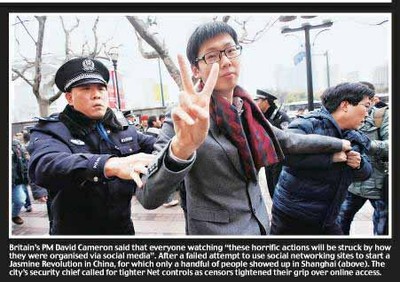

"There are checks and balances in the legal systems of most democracies that allow appropriate investigation. For example, being able to subpoena phone records in a criminal investigation, while preserving the rights of the user as much as possible," says Crossfield. WHILE, reportedly, police in London have vowed to track down those suspected of stirring violence through Twitter, they mainly blamed BlackBerry Messenger. "Everyone watching these horrific actions will be struck by how they were organised via social media. Free flow of information can be used for good. But, it can also be used for ill,” British Prime Minister David Cameron told Parliament. But, there is no reason social networking should be treated more harshly or subdued in a graver way than any other form of communication, says Crossfield, as they these are not the real threat to the state. "It’s important to remember that social networks are neutral -- just a medium to connect people. The paper you write on is not at fault for the words you use," he says, "If any state, democratic or otherwise, decides to categorise social networks as a threat, what it really means is that they feel threatened by what people are saying and the ideas that are being discussed among them. And that leads to censorship, not democracy." But not just during civil unrest, BlackBerry encrypted messaging service was used by terrorists during 26/11 terrorist attacks in Mumbai to communicate as other services were blocked by the state. Since then, the Indian government has been urging Research-In-Motion (RIM), the maker of BlackBerry, to provide them with messages in a readable format or stop services.

"It is legal to intercept a communication made on a social media in India under the Telegraph Act and the IT Act, which is partially a limitation on privacy," says Sunil Abraham, executive director, Center for Internet and Society. But, Abraham adds, this censorship should not be generalised and the group concerned needs to be targeted and it should not target any specific ethnic group for what their peers have done.

"This has nothing to do uniquely with social networking. Any technology can be used for both good and bad purposes. Totalitarian regimes can use social networking to establish their agendas, while the same platform can be used by the protesters," says Balaji Parthasarathy, professor at International Institute of Information Technology-Bangalore. It can also be used, as was seen during the recent blasts on July 13 in Mumbai, in helping friends and family of victims when cellular networks had been jammed for security reasons. The Twitter tag ‘#here2help’ was one messaging vehicle that urged hundreds of netizens to help victims stranded after the blast. Which is why, says Parthasarathy, if social networking or even a telephony service poses serious threats to a democratic state, there should be clear-cut guidelines from the government.