Dictionary words in software patent guidelines puzzle industry

Terms not defined in draft guidelines on patents for computer-related inventions leaves room for misinterpretation

The article by C.H.Unnikrishnan was published in Livemint on August 26, 2013. The Centre for Internet and Society's work on access to knowledge is mentioned.

Could the simple Latin phrase, per se, which translates as “in itself”, lead to confusion in verifying whether a computer-related invention deserves a patent or not? Some members of the $108 billion Indian information technology industry, intellectual property (IP) law firms and anti-patent lobby groups say it can.

The inclusion of some terms that are not defined by local laws in the government’s draft guidelines on patents for computer-related inventions (CRIs) leaves room for ambiguity and misinterpretation when examiners grant or reject such a patent, they say. The guidelines were released in early August.

The terms include ‘per se’, algorithm, hardware, firmware —and CRI itself.

CRI “has not been defined in any of the Indian statutes and is construed to mean, for the purpose of these guidelines, any invention which involves the use of computers, computer networks or other programmable apparatus and includes such inventions, one or more features of which are realized wholly or partially by means of a computer programme/programmes”, the Indian Patent Office (IPO) acknowledged in the draft guidelines, and called for feedback from industry stakeholders by 8 August.

|

Patent examination is the most crucial function performed by a patent office. An examiner verifies the invention claims made by an applicant by relying on scientific parameters, industrial applicability and previously known technologies, among others, to decide whether the claims are genuine and deserve a patent. IPO’s draft guidelines are aimed at helping examiners in this task. However, with new technologies, the task of granting or rejecting patents has become tougher, as acknowledged by the patent office, in its draft guidelines. The confusion is only compounded with the inclusion of dictionary terms such as per se. The Indian Patent Law does not contain any specific provision regarding the protection of computer software that includes programs, musical and artistic works, studio and video recordings, databases and preparation material and associated documents such as manuals. India does not grant pure software patents (i.e., a patent over a “computer programme per se”). |

|---|

Software, instead, is protected by the Copyright Law, similar to literary and aesthetic works.

In the feedback, a copy which was reviewed by Mint, India’s largest software services exporter Tata Consultancy Services Ltd (TCS), said it “is happy to note that IPO is taking the right steps in the direction of protecting inventions...Moving from the notion of ‘Computer Implemented Invention’ to ‘Computer Related Invention’ itself is a positive shift...”

|

“Primary objective of the CRI guidelines, as expected and understood by the stakeholders, is to deliberate on the meaning of “per se” in Section 3(k) for Software Inventions with example pertaining to Software Inventions and not interpret them to be the Hardware-led inventions,” said TCS in its feedback. It added that “while examining the technical character of a CRI, mere usage of the words such as enterprise, business, business rules, supply-chain, order, sales, transactions, commerce, payment, etc. in the (patent) claims should not lead to conclusion of the CRI being just a ‘Business Method’ without any technical character. These terminologies actually qualify the contextual utility and fitment of the inventions..”

|

According to Rajiv Kumar Choudhari, a lawyer specializing in IT patent law, a computer program is software ‘per se’ because there may be no transformation of data/signal/input, or there is no tangible benefit to the device if this software is run on the device. “The benefit to the device may be in terms of efficiency, or increase/decrease in certain attributes,” he said in a blog in SpicyIP where he analyzed software patenting position in India earlier.

In such cases, if the applicant fails to define the exact benefit to the device in a tangible manner, the examiner may refuse to grant a patent. In January 2012, for instance, the Delhi patent office rejected a software patent application filed by Netomat Inc., on grounds that it did not fulfil the requirement of Section 3(k).

According to section 3(k) of the Indian Patent Act, “a mathematical or business method or computer programs per se or algorithms” are not inventions.

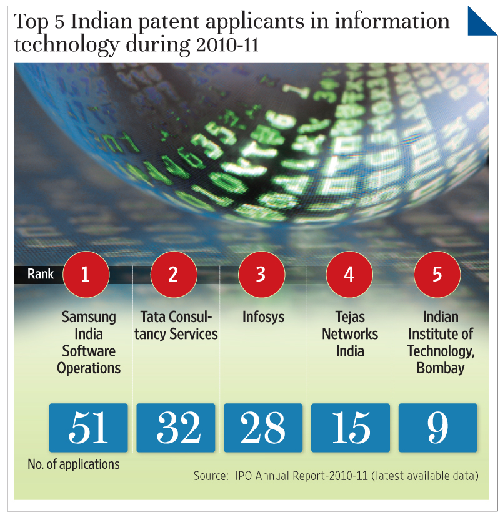

Between 2006 and 2011, the latest available data, 34,967 IT patent applications were filed with the Indian patent office. It granted about 5,594 patents during the same period.

“We hope that through this consultation (feedback) the prevailing evaluation methods for computer related inventions will become more efficient and encourage the Industry to file and protect their IP. However, we have some major concerns related to the draft guidelines,” said Nassom, the country’s software lobby body.

Overall, the guidelines appear to be “restrictive and may be a hindrance to grant of patents in India, even when such rights would be granted in other countries like Europe, Japan, etc,” said Nasscom, adding that “over a period of time”, it will discourage innovative activities from being carried out in India.

For instance, Nasscom pointed out that since the patent office has not defined ‘per se’, the phrase “computer program per se” should mean a set of instructions by itself or computer program by itself. “This meaning is generally accepted even in the UK and before the EPO (European Patent Office),” it added. The software lobby body has suggested that the scope of the “per se” limitation in Section 3(k) should be changed to cover hardware features, irrespective of whether the features are novel or not.

The guidelines, said Nasscom, seem to imply that for computer program-related claims to be allowed, the software needs to be “machine specific”, which “will unfortunately exclude patent protection for any computer-implemented invention designed to be interoperable across platforms, and not specific to a machine”.

In its feedback to the patent office, the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), an organization that works on Internet privacy-related issues, underscored the complexity that new technologies could introduce by citing the example of CRIs in the field of data storage.

The first compact disc (CD) was invented in 1982, the digital video disc (DVD) in 1995 and the flash drive in 1999.

“While each of these inventions was far superior to their predecessor, the time between each incremental innovation has drastically reduced,” CIS noted in its feedback

“If an invention can become obsolete in as little as 2 years, it would make little sense to grant monopoly rights for 20 years. So even if a CRI passes the three tests of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability, it needs to be evaluated from the perspective of its possible obsolescence. In such a scenario, the examiner should look at the history of innovation in that particular field to ascertain that the invention does not become obsolete in a short time.”

Also consider for instance the term, “business methods”. It involves a whole gamut of activities in a commercial or industrial enterprise relating to transaction of goods or services but “the claims are at times drafted not directly as business methods but apparently with hitherto available technical features such as Internet, networks, satellites, tele-communications, etc”, the draft stated.

“The exclusions are carved out for all business methods and, therefore, if in substance the claims relate to business method even with the help of technology, they are not considered patentable,” the guidelines added.

The Japan intellectual Property Association, in its reaction to the India’s new CRI patenting guidelines, also noted that recent computers, including processors or memories, mostly do not rely on any specific programs.

“In addition, software-related inventions should be patentable originally for their functioning on the basis of novel computer programs in combination with general purpose devices. However, these computer-related inventions would be excluded from protection under the new standards for patentability,” it cautioned.

The draft guidelines “have interpreted and applied Section 3(k) of the Indian Patent Act 1970 in a more restrictive way to conclude as to what is patentable, which is a cause of concern to various stakeholders”, said Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industries (FICCI) in its reaction.

Software patents remain an emotive issue.

Their proponents argue that patents promote investment in research and development, accelerate software development by making previously unknown and not obvious software inventions public and protect IP of software companies. They also encourage the creation of software companies and jobs and increase the valuation of small companies, the proponents add.

Critics counter that traditional copyright has provided sufficient protection to facilitate massive investment in software development and that most software patents cover either trivial inventions or inventions that would have been obvious to persons of ordinary skill in the art at the time the invention was made.

Globally, patents in the IT and software sector are being revisited due to litigation and compensation claims over misuse of patents including the much-hyped patent battle of Apple Inc. with Samsung Electronics and Google Inc. with Microsoft Corp.

In June 2008, technology companies including Google, Intel Corp, Oracle Corp, Cisco and Hewlett-Packard Co. set up the ‘Allied Security Trust’ to address the risk of patent-infringement suits by buying those patents which they feel are most important to their businesses.

AST has 26 members from Europe, North America and Asia. It buys patents that its members have expressed interest from the patent holder, and the cost would be deducted from those companies’ Escrow accounts. AST argues that non-practicing entities, or NPEs, also known as patent trolls, produce no products or services of their own, and yet acquire patents—sometimes hundreds of them—with the sole intention of asserting their right and conduct patent litigation to extract settlements or licensing fees.

In 2008, AST estimated that it costs operating companies an average of $3.2 million through the end of discovery and $5.2 million through trial to defend cases in which there is more than $25 million at stake.

The costs of determining if a particular piece of software infringes any issued patents are too high and the results too are uncertain. A software patent costs, on average, around $20,000, it said.